Many years ago, and as many miles away from the microcosm of life in the city—at least as we experience it in Athens—, autumn meant much more than the return of summer holidaymakers, the reappearance of traffic, the gloom of going back to the office, or the anxious readjustment to the “hamster wheel” of a new year.

In the slower rhythms of the Greek countryside, where urbanization is seen only on TV and tablet screens, before the climate crisis stretched summer well into late October, life marched to a different beat.

Without apartment blocks to block the view, the eye could range far and wide across fields and hills, and people both had time to listen to nature and observe its changes and were in the habit of doing so. There lies a different kind of autumn. One full of colors, scents, flavors, music, and celebration: a collective autumn.

Below, we revisit some of Greece’s autumn traditions. Some live on, others have faded or been transformed, but most would have been familiar to those of our parents or grandparents who grew up in the provinces. Some have evolved in step with modern life, keeping local identity alive in today’s Greek autumn. For those who visit rural Greece at this time of year, these customs are not just memories—they are still very much alive.

The famous stone bridge of Kokori in the fall in Zagori, Greece.

September: Τhe Grape Harvest Month

Long before “low-alcohol” or “low-calories” wines became fashionable, wine in Greece was—and remains—an essential companion at the dinner table: a symbol of celebration, companionship, and sharing.

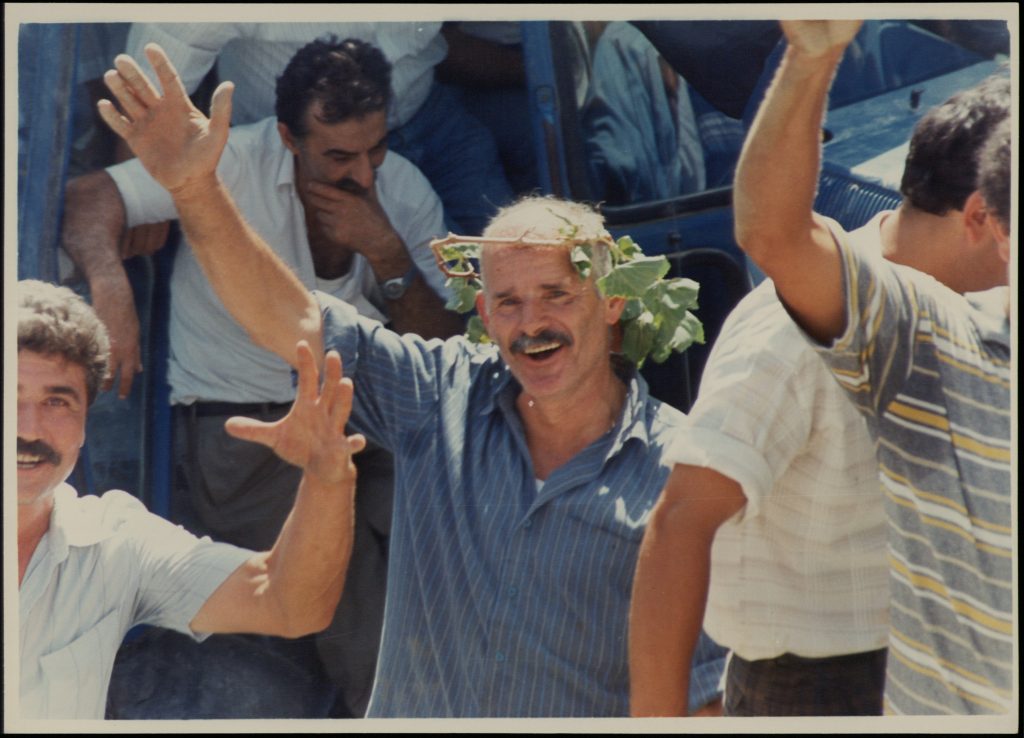

For the people of the countryside, even the labor of the grape harvest was cause for celebration, because the hard work in the heat of the sun carried within it the joy of community and the promise of reward.

As folklorist Dimitrios Loukatos records, the harvest—beginning after August 15 and peaking in September—was both back-breaking and festive. Neighbors, friends, and relatives would gather before dawn, load the animals, and head to the vineyards to the accompaniment of songs and laughter. The day’s toil always ended with a feast at the vineyard owner’s home—a celebration of abundance and togetherness.

Once the grapes were pressed for must and wine, it was time for the first sweets of the season: petimezi (grape syrup) and children’s favorites like moustalevria—a pudding of must and flour, topped with sesame and walnuts—and moustokouloura, grape-must cookies.

In Crete, Chara, 57, from Heraklion, remembers women gathering to make these treats and notes the importance of raisin production, a hallmark of Crete and the Peloponnese with a long export tradition.

Saint George the ‘Tipsy’

The first barrels of the new wine were traditionally opened around the feast of Saint Demetrios on October 26, Loukatos notes. In the Peloponnese, many households would bring a bottle to church to be blessed, then pour a few drops into each barrel for good fortune.

But in areas with a church dedicated to Saint George, the first barrel was opened on November 3, on the spirited feast of “Saint George the Drunkard” (Agios Georgios Methystis). On Crete, where the weather remains mild, worshippers bring their own demijohns of wine to the countryside chapels, and the day quickly turns into an open-air feast with meat, sweets, and freshly uncorked wine. Similar festivities take place in Karpathos and across the Dodecanese.

Around the Still: Distilling Tsipouro and Raki

The gifts of the grape don’t end with wine. What remains after pressing finds new life in the kazani, the bubbling still in which the fiery spirits tsipouro and raki are born.

Still celebrated across Greece—particularly in Central Macedonia and Crete—the kazani marks the start of the distillation season, a communal event at which distillers transform the grape skins and pips into clear, strong spirits. Locals gather for food, music, and dance—an autumn party with deep roots.

The kazani marks the start of the distillation season, a communal event at which distillers transform the grape skins and pips into clear, strong spirits while locals gather for food, music, and dance.

In the mountainous village of Moni, Naxos, Maria Magganari, who has roots on the island, tells us, “The custom has always been part of local life. And it’s thriving now, with distillers from across the island coming together to make raki.”

From Heraklion, Yiannis, 65, recalls countless local kazania: “The first raki that flows from the still is called protoraki—it’s very strong, so we dilute it with water. We always roast ofti potatoes in the ashes of the fire that fueled the still, and grill meat alongside.” Today, he adds, travel agencies even include kazani experiences for visitors eager to join in the celebration. Raki also gives us rakomelo—raki mixed with honey and spices like cloves—which, as Yiannis notes with a smile, “we Cretans consider a natural antibiotic.”

All About the Fresh Olive Oil

From early November, families across Greece turn to the olive harvest—a job anyone fit enough to climb, shake, or rake the trees can take part in. In days gone by, neighbors and relatives would work collectively: one day in one family’s grove, the next in another’s.

Evenings were for sorting—women and children gathered around a large cloth, separating olives from leaves before taking them to the olive press, where the millers would sing and chat as the millstones turned. The first fresh oil was handed back to the head of the household, and the miller was paid with a portion of it.

When the first green oil (agourelaio) flowed, women would prepare simple, joyful meals—frying ladopita, pancakes, or baking fresh bread to dip into the golden liquid. Left-over oil from the previous year was often turned into homemade soap.

An old childhood dessert, ‘tiganites’ is a Greek pancake fried in fresh olive oil and served with honey, or sugar.

As Loukatos reminds us, olive oil holds a sacred place in the Orthodox tradition. A timeless symbol of purity, a medicine, and an offering to saints and ancestors alike, the oil is used in baptism, weddings and funerals, as well as in vigil lamps and blessings.

The ‘Nychteria’: Nights of Women’s Work and Gossip

As the days shortened and nights grew cooler, women of the same neighborhood could no longer gather outdoors as they did in summer.After the feast of Saint Demetrios, they began the nychteria—evening gatherings of women of all ages and social backgrounds.

These were part work, part therapy: women brought their knitting or embroidery, cooked, sang, teased one another, told riddles and stories—even shared secrets and tales of love. The younger ones listened and learned about life, marriage, and love from those older and wiser than them.

The hostess always offered something simple to eat: roasted corn, chestnuts, or nuts—enough to keep the hands busy and the mood light. The nychteria were more than a pastime; they were a ritual of companionship and storytelling, where laughter softened hardship and work became celebration.

‘Polysporia’ and Saint Barbara

In Loukatos’ writings, wheat is described as the farmer’s “golden regulator,” and sowing season was one of the most sacred times of the year. On November 21, the Feast of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary, rural families prepared polysporia—a soup of mixed grains and legumes (wheat, corn, barley, chickpeas, beans) eaten together to honor the season.

This custom is rooted in ancient rites such as the Pyanopsia and the worship of Demeter, the goddess of fertility and the harvest, and is a blend of pagan and Christian traditions. The Virgin Mary came to be revered as the protector of farmers and fields, who ensured a fruitful new season.

Similarly, Saint Barbara was believed to protect children from smallpox. On December 4, mothers would prepare a sweet dish, often a honey pie called Varvara, blessed by the priest, then shared with neighbors. In Thrace, the offering took the form of wheat and pulses—a custom reminiscent of the Turkish Ashure.

According to folklorist George Megas, this custom was seen as a continuation of ancient offerings to Hecate, goddess of crossroads, light, and magic. In those earlier rituals, food was placed on Hecate’s altar during the last evenings of the month, when the moon was still young.

Farewell to the Fields: A Funeral for Leidinos

On the island of Aegina, between March and September, farmers once took a light supper at dusk, known as leidino, after long days in the fields. With the arrival of autumn and shorter days, the evening meal was no longer needed, with its cessation symbolizing the end of the agricultural season.

In the village of Kypseli, this transition became a ritualized “funeral” for Leidinos—a humorous yet deeply symbolic ceremony marking the death of summer and the rebirth of autumn.

Women would fashion a straw-stuffed effigy of a young farmer, parade it through the streets with children singing farewell laments, and finally bury it with kollyva (boiled wheat offered for the dead). The celebration ended with feasting and music—a joyful acceptance of life’s cycles.

In February 2025, this unique Aegina custom was officially added to Greece’s National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage—a fitting tribute to a living symbol of the Greek autumn and its enduring connection between labor, faith, and festivity.