The Ancient Greeks believed the olive tree sprang from a heavenly battle between the goddess of wisdom and warfare, Athena, and the king of the sea, Poseidon. The story goes that both gods offered their followers gifts in a competition to become the patron deity of the modern Greek capital.

Striking the Earth with his trident, Poseidon spouted a salty spring from the Acropolis that proved of little use to the city’s residents. However, Athena’s gift of the olive tree was more practical, offering the Athenians fruit to eat, oil for their pots and lamps, and wood for warmth. And so the city dwellers chose Athena and named their city Athens in her honor.

While the olive is still a sacred part of Greece’s natural beauty, the modern-day appreciation of the tree is grounded in the abundance of fruit and oil it provides, rather than its mythical origins. But to many in the diaspora, including myself, this story helped us understand the significance of this “blessing from above” our ancestors once cultivated.

To many of us, the olive tree, which was once so intertwined with the everyday lives of our grandparents and their parents before them, is now the centerpiece of a constructed memory of stories passed down through generations.

On my mother’s side, my grandparents come from Krokees in the southern Peloponnese, where olive trees were a crucial part of the local economy. But when they braved the Atlantic crossing to North America in search of opportunity, their symbiotic relationship with the land they grew up on was severed.

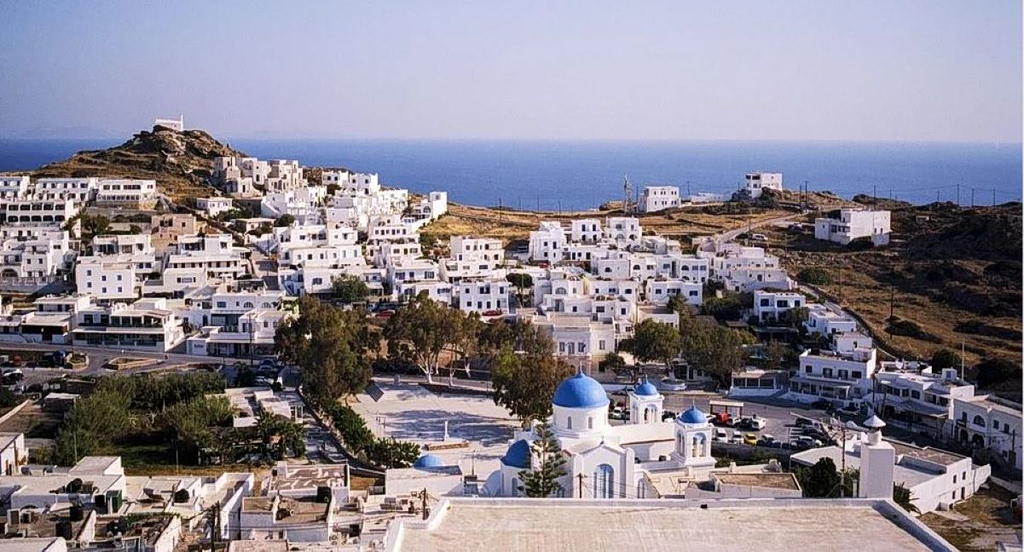

To stay connected to their homeland, they passed down stories of sparkling ocean views, freshly picked oranges and figs, and the centuries-old olive groves they once roamed to their descendants, the Greek diaspora—me and my (many) cousins.

The first and last time I had been to Krokees was in 2014, but this year, I had the opportunity to travel there with a group of family members to visit my grandfather’s olive groves, lend a hand during the harvest, and turn what was once a folktale into a reality.

Heading to The Fields

Our day of harvesting started early at 6 a.m. As the light of dawn slowly crept over terracotta rooftops, my father, grandfather, and family friend and farmer Yiannis Farlekas enjoyed a slow conversation about our day ahead over coffee and lalagithes—twisted strings of fried dough that originate from the Mani Peninsula and surrounding areas.

I’ll admit that my sister and I slept in a little longer than we’d aimed for, but by 9 o’clock, when uncles and cousins had arrived, we hit the road in a procession of rental cars and farm trucks. We were heading to the groves, which are in a nearby village called Kakavo.

Stepping onto the soil, my grandfather took my sister, my cousin and me on a slow, introductory walk through the grove, picking nettles on the way for tea, his favorite.

“The six of us youngsters came to this tree with our parents with bags of clothes and built a tent when the Nazis invaded,” he said, stopping in front of a thick, gnarled tree trunk. “It has seen my father, his father, and his father before him.”

Not only do the roots of these trees connect my family to the land, they are also interwoven with the roots of the Farlekas family, the multi-generational farmers who own To Fi Tis Fisis, meaning, “The F of Nature” (the “F” is for “Farlekas”). They cultivate my grandfather’s olive groves now.

Dimitris Farlekas, the third generation of the family to run To Fi Tis Fisis, is my grandfather’s first point of contact when it comes to olive oil, as it was his idea to push his family’s practice further.

“My father and his father, that was their job. They raised me and my siblings in the agricultural sector; they had the fields, and now they’ve left them to me. The only extra thing I thought I would do was make a label and standardize the oil to sell it,” he told me.

While the ethos behind the harvest has remained consistent, the approach has largely been modernized since my grandfather’s day, to support the maintenance of expanding fields.

The process was relatively straightforward. Rather than solely picking by hand, we used electric sticks designed to rake or shake olives from the tree. That way, we could maximize the harvest without damaging the fruit. The farmers lay large mesh nets at the bottom of the tree, to catch the olives, which makes transferring them into sacks far less intimidating.

Of course, we picked a few ripe olives to sneak a taste.

An Intimate Industry

After about two hours of raking branches, sneaking photos, and slipping into nearby citrus orchards it was time for a legitimate snack break. Dimitris’ father, Yiannis, gathered us all into the small farmhouse for a brief intermission.

The emerald-green door stood open to let in the sunlight, and cigarette smoke began rising into the air as we each reached for packaged croissants and cups of instant coffee. We all squeezed together on mattresses, and Yiannis and my grandfather began discussing the next day’s plans for the oil production, village gossip, and their families’ history.

Though I’m still working on my Greek, in between dry coughs and belly laughs, I was able to grasp that the relationship between my grandfather and Yiannis is rooted in something far more profound than business. Because it is rooted in respect for the olive tree as a collective asset — something that is to be enjoyed by all, not hoarded—and in their solidarity as members of the same community.

When Yiannis’ father, Konstantinos Farlekas, returned from the war in the 1950s, he needed a job. Starting in construction, he saved enough money to buy a small plot of land. It was there that he planted the family’s first olive trees to satisfy their yearly needs. Eventually, he bought more land, expanded the grove, and planted more trees.

When my grandfather left for Canada with his family in the 1960s, there was no one to look after his trees, but he didn’t want to abandon them. Growing up in Krokees, his father had a strong relationship with the Farlekas family, who had begun to make a name for themselves locally for their olive groves, which were near his own. So, my grandfather entrusted his trees to the family.

“I’ve seen a photo somewhere of your great-grandmother with my grandfather. They had a good relationship, especially once your grandfather left the fields and mine began working them,” Dimitris told me.

In Krokees, many families that left in groups for cities like Montreal and Boston were still tethered to their village by olive trees. Some sold their land to the Farlekas family, but others made the same deal, making others stakeholders in the cultivation process, but holding on tight to these totems of heritage.

Understanding Identity

But aside from giving us fine-tasting oil, the care the Farlekas family has lavished on our groves has allowed my family to retain a connection with our roots that goes beyond citizenship and surnames.

I can’t speak for everyone in my family, but walking through the soft grass of my grandfather’s olive grove felt like a homecoming. As I sat under the branches on gnarled tree trunks, peeling tangerines and cracking open almonds my cousin and I picked on our way to the field, I felt like I was at a family reunion, getting to know relatives I had only heard of in passing, but who had known me since birth.

These trees know a part of me that is reflected in the long nose and dark eyes I inherited from my grandfather. They know a part of my history that I’m still unraveling.

Those of us who have the luxury of enjoying fruit and oil from our family’s olive trees should not take it for granted. We have the opportunity to see our heritage and the metaphorical roots we long to reconnect with made literal by the sanctity of these trees.

Every drop of oil, whether coating summer vegetables or a comforting plate of fried potatoes, holds ancient wisdom; memories woven through generations that tell stories of resilience and hold secrets to longevity.