Eighty-five years ago today, in the middle of World War II, Ioannis Metaxas was sent an ultimatum by Benito Mussolini, demanding that Italian armed forces be granted unimpeded access to the Greek-Albanian border and the occupation of strategic areas of Greece.

In his address yesterday, Greek Minister of Defense Nikos Dendias recalled Metaxas’ response to this ultimatum as the moment when Greece “stood firmly against advancing Fascism and Nazism,” with a simple “Ohi,” “No,” thus starting the Greco-Italian War on 28 October, 1940. Now, the day is celebrated as a national holiday in Greece, serving as a reminder of the Greek resistance.

Since then, World War II has been a popular subject in Hollywood for decades, bringing global stories from generations past to the contemporary silver screen. One of which, Mediterraneo (1991), has become a cult classic across the Greek diaspora.

Warning, spoilers ahead!

Summertime Cinema

An Italian war comedy set on the small Dodecanesian island of Kastellorizo during World War II, the film follows a group of soldiers sent to occupy the island in June 1940, around the time Italy joined the Axis Powers. Eventually, the group is cut off from the rest of the Italian army and is left clueless about the war’s following events.

Initially afraid of the Italian soldiers’ arrival, the islanders go into hiding, but as they realize the soldiers’ harmless nature, they return to their jubilant island lifestyle, filled with laughter, dancing, and drinking.

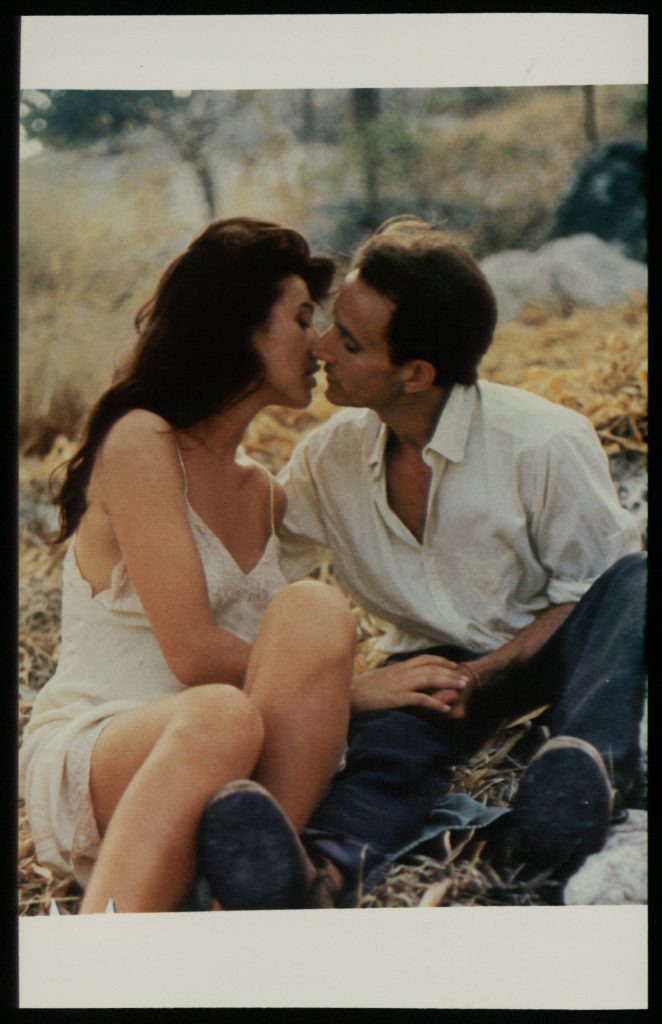

As the soldiers continue to familiarize themselves with the island, befriending the local priest and embarking on Dionysian love affairs — two brothers with a local shepherdess and one soldier, Farina, with the village prostitute, Vasilissa, whom he would eventually fall in love with and marry.

Lazily melting into the sun-soaked lifestyle of the islanders, the soldiers are awoken when an Italian pilot arrives on Kastellorizo three years later and informs them that Mussolini has fallen and Italy has switched sides. Eventually, the group returns to Italy, leaving Farina behind with his new love as they pursue her dream to open a restaurant.

Finally, three soldiers are reunited on the island, reflecting on the many years they’ve spent apart, and grieving the passing of Vasilissa.

Mediterraneo is a heartwarming tale of love, hope and loss. However, while it presents itself as a World War II film, the context in which the story unravels is largely inaccurate.

Historical Fiction, or Simply Fiction?

In 1923, Italy formally annexed the Dodecanese. While the early years brought the region welcome economic prosperity, views began to shift in the late 1930s, right before the story of Mediterraneo would have taken place.

One of the first people the soldiers speak with is the town priest—a soft-spoken older man who learned Italian while living in Rome. The soldiers tell him they don’t want to disturb the island, but ask why there are so few men.

By this time in the war, the island would have already been under years of Italian occupation. Still, in the film, the priest tells the soldiers that before they arrived, German military forces had invaded and ransacked the town, taking their men as prisoners. He tells the men that Italians are the lesser of two evils, followed by the first utterance of “una faccia, una razza,” meaning “one face, one race.” A phrase popularized by the film, meant to delineate the cultural kinship between Italians and Greeks.

Eventually, the priest would discover one of the soldiers, Montini, and his talent for painting, and commission him to finish painting the church wall icons. Modestly shrugging off the commission, he eventually agrees, deepening his friendship with the priest.

The ‘lesser of two evils’ framework permeates the entirety of the film, subconsciously absolving Italian forces of playing a role in the war crimes of the Axis Powers in collective memory. In reality, however, Italian presence on the Dodecanese islands during World War II was a far cry from that displayed in the film.

The Italian Dodecanese

For years, Dodecanesians were under the governance of Mario Lago, an Italian diplomat. Under Lago, the islands were caught between two worlds, the native Greek and foreign Italian, netted by religious and educational policies.

The former was the intended severance of the Dodecanesian churches from the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, isolating the islands from the rest of the Greek world.

While this was justified by parallel changes between political and ecclesiastical boundaries, elites on the islands and elsewhere grew suspicious of underlying political motives to weaken the Church’s authority and pave the way for a broader sweep of Italian control, eventually converting the islands to Catholicism.

The latter policy mandated Italian-language classes in schools and required teachers to obtain degrees from Italian institutions, delegitimizing Greek universities.

However, due to Lago’s slow pace of Italianization, he returned to Rome, and in 1936, the Dodecanese fell under the governance of Cesare Maria De Vecche, whom many Dodecanesians remember as “the fascist.” Under De Vecche, all Greek secondary schools were shut down, and speaking Greek in public became criminalized. De Vecche’s governance blatantly threatened Greek identity.

Italiani Brava Gente

Since Mediterraneo’s release, historians have criticized the film for perpetuating the “Italiani brava gente” trope — meaning “Italians, the good people” — the idea that Italian soldiers did not participate in the war crimes of the Axis Powers, including the occupation of the Dodecanese islands. While it has certainly led to historical amnesia for many communities outside the Dodecanese, historian Nicholas Doumanis argues that many Greeks paradoxically remember the Italian presence on the island as a form of “humane imperialism“.

In his research for “Myth and Memory in the Mediterranean,” Doumanis writes that many Dodecanesians he interviewed “shuffled between patriotic rectitude and charitable praise for the foreign oppressor, seemingly unable to negotiate the contradictory demands of a national culture they revered and the truths elicited from their collective social experiences.”

So, while October 28 is more a celebration of the Greek resistance against Fascism, part of the remembrance is the acknowledgment of a multifaceted history. On October 28, we should not only remember the Greek military resistance but also the resilience against attempts at cultural erasure.