The EU–Mercosur trade agreement, after more than two decades of negotiation, represents one of the European Union’s most ambitious trade initiatives. By reducing tariffs and opening markets between the EU and four South American economies—Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay—the agreement promises gains in industrial exports and consumer welfare. Yet its reception across Europe has been uneven. For Greece, the response has been lukewarm rather than hostile, reflecting a balance between limited export opportunities and long-standing structural weaknesses in agriculture. This cautious stance contrasts sharply with the outright resistance of countries such as Ireland, highlighting how the same trade agreement can expose profoundly different national economic realities.

Trade Theory and the Reality of Managed Liberalization

In classical trade theory, the EU–Mercosur agreement aligns with comparative advantage: Mercosur economies specialize in land-intensive agricultural production, while the EU exports higher-value industrial and manufactured goods. In theory, such specialization should raise aggregate welfare on both sides.

In practice, however, the agreement is not a textbook free-trade deal but a case of managed liberalization. Market access for politically sensitive sectors such as beef, poultry and sugar is tightly constrained through tariff-rate quotas and safeguard clauses rather than full tariff elimination. At the same time, the EU’s food safety and animal-health standards remain unchanged, and hundreds of European geographical indications are explicitly protected, preserving value tied to origin rather than scale. These design choices reflect political and social realities: trade liberalization is permitted only where it does not threaten agricultural stability, regulatory standards or rural livelihoods, even at the cost of some theoretical efficiency gains (European Commission, EU–Mercosur Agreement Factsheet).

Greece: Opportunities and Vulnerabilities

For Greece, the agreement presents a narrow but tangible upside. GI-protected products such as feta cheese, Kalamata olives, and selected wines stand to benefit from improved access to Mercosur markets and stronger intellectual property protection. As outlined in To Vima’s analysis of the deal’s implications for Greece, these gains are real but modest, constrained by limited export capacity and weak branding penetration beyond niche markets.

On the downside, Greek agriculture remains structurally exposed. Livestock producers and farmers in commodity-adjacent sectors fear price pressure from Mercosur imports, even under quota restrictions. More importantly, Greece’s agricultural sector is characterized by small farm size, fragmented land ownership, limited access to capital, and heavy administrative burdens. These features blunt the benefits of trade openness and amplify the risks, explaining why public and farmer sentiment has been cautious rather than enthusiastic.

These mixed incentives help explain why Greece’s response has been measured rather than confrontational—a stance that becomes clearer when contrasted with the position adopted by Ireland, another agricultural EU member state facing the same agreement under very different structural conditions.

Ireland’s Reluctance and Divergent Modernization Paths

While both Greece and Ireland have voiced concerns about the EU–Mercosur agreement, Ireland’s opposition has been far more explicit and politically firm. Irish farmers and agricultural organizations argue that even limited tariff-free quotas for South American beef could depress prices, undermine EU production standards, and threaten rural livelihoods. This pressure has translated into clear political signals that Ireland is prepared to oppose ratification unless stronger safeguards are introduced.

This contrast echoes the sharply divergent modernization trajectories of Greece and Ireland that I analyzed years before the current Mercosur debate, in a comparative article co-authored with Professor George Bitros and published in To Vima. That earlier work examined the long-term structural transformation of Greece and Ireland, not trade policy per se. Its relevance today lies in how it also helps to explain the present divergence in the Mercosur reactions of these two nations. Ireland’s resistance to Mercosur is not the product of institutional weakness or fear of openness. On the contrary, it reflects confidence as in Ireland, agriculture functions as a strategic sector within a highly productive, export-oriented economy that has already integrated successfully into global markets. Viewed through this lens, for Ireland the Mercosur agreement (in comparison to the Greek response) appears as an uneven form of liberalization, raising concerns about the gradual erosion of hard-won competitive advantages rather than the creation of new ones.

Greece’s ambivalence, by contrast, is rooted less in protecting a mature agri-food powerhouse and more in coping with unresolved structural constraints. Where Ireland resists the deal to defend competitiveness, Greece hesitates because its agricultural sector has yet to complete the modernization that would allow it to benefit meaningfully from openness.

This distinction is crucial, because Greece’s challenge is not primarily whether to accept trade liberalization, but whether its domestic institutions are capable of converting external openness into sustained agricultural competitiveness.

Redistribution and the European Political Economy

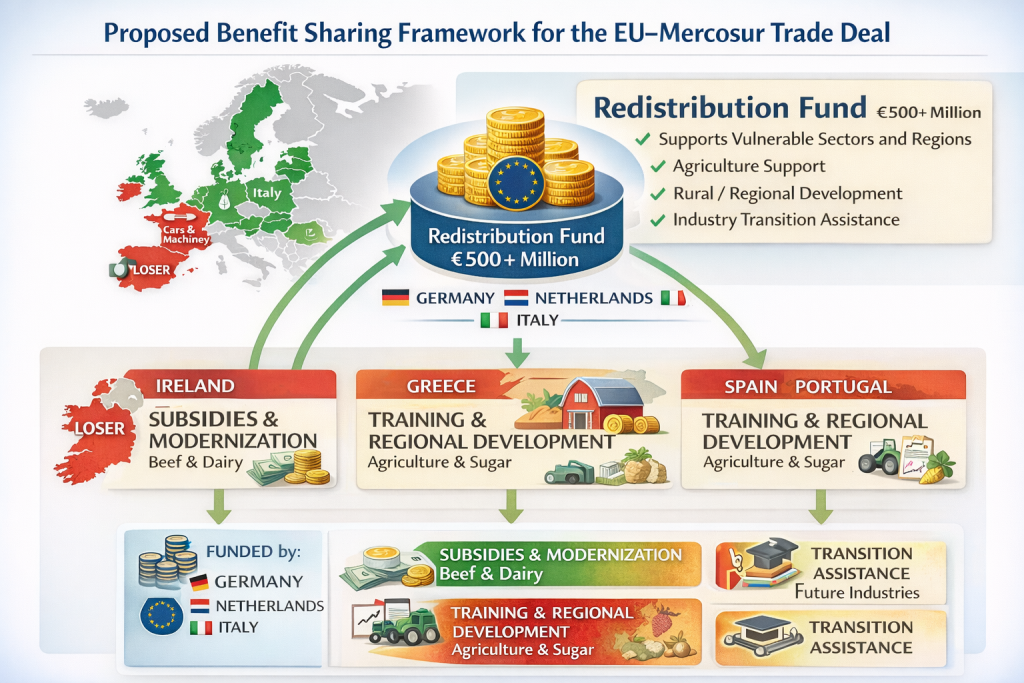

This asymmetry raises a broader EU-level question: should the gains from trade be redistributed from winners to losers? As illustrated in Figure 1 (the accompanying infographic), a plausible framework would channel a share of industrial gains—primarily accruing to countries such as Germany and the Netherlands—into targeted support for vulnerable agricultural regions.

Figure 1: Benefit-Sharing Framework for the EU–Mercosur Deal

The infographic introduces a redistributive mechanism in which gains from industrialized EU exporters help fund compensation schemes, rural development, upskilling and modernization for vulnerable agricultural sectors in Greece and similar economies. This is not only a moral case for redistribution to uphold EU cohesion, but also a pragmatic policy solution to strengthen the domestic capacity of Greek agriculture to adapt and compete.

For Greece, such redistribution would be most effective if tied explicitly to reform: modernization grants, rural infrastructure, skills training, and incentives for cooperative farming structures. This approach aligns redistribution with competitiveness rather than permanent protection, echoing the logic of the Pissarides reform agenda.

Mercosur as a Political and Geopolitical Flashpoint

While structural reform and redistributive mechanisms are critical to how Greece and other EU nations engage with Mercosur, the agreement’s significance has also expanded into the realm of EU internal politics and geopolitics—shaping alliances, trade strategy and domestic debates across member states.

As analysis by the European Parliament’s research service makes clear, the EU–Mercosur agreement has evolved well beyond a technical trade negotiation into a geopolitical instrument embedded in the EU’s external relations strategy. The agreement is increasingly framed as part of Europe’s effort to deepen ties with Latin America, diversify economic partnerships, and assert strategic autonomy in a global environment shaped by U.S. retrenchment and rising Chinese influence. At the same time, this geopolitical ambition has sharpened internal EU divisions. Member states with strong industrial export profiles tend to emphasize Mercosur’s strategic and commercial value, while agriculturally sensitive countries frame the deal as a threat to domestic production models, environmental standards, and rural cohesion. In this sense, Mercosur has become a symbolic fault line within the EU, revealing tensions between economic openness, political legitimacy, and competing visions of Europe’s global role.

The EU–Mercosur trade agreement exposes the limits of abstract trade theory when confronted with Europe’s uneven economic landscape. For Greece, the deal offers incremental opportunities but also highlights deep-seated structural weaknesses that dampen its benefits. Unlike Ireland, whose opposition reflects the defense of a strong and competitive agricultural sector, Greece’s lukewarm response is shaped by incomplete modernization and institutional fragility.

Whether the agreement ultimately benefits Greece depends less on tariff schedules than on domestic reform capacity and EU-level political choices about redistribution and adjustment. If accompanied by structural reform and targeted support, Mercosur could become a catalyst for long-delayed agricultural modernization. Without them, it risks reinforcing the very vulnerabilities that have long constrained Greece’s integration into global markets.