At the end of last year, I saw the performance “Somewhere a Voice Passed” at the small theater of the bijoux de kant group, directed by Giannis Skourletis. It was a cleverly staged presentation of songs composed by Christos Theodorou, set to well-known poems by Napoleon Lapathiotis.

The space itself was abstract, reminiscent simultaneously of a museum and of locations for gay gatherings, such as the Zappeion (where, during its nighttime walks, the aesthete Lapathiotis had acquired such a legendary status that it became a novel in the 1920s).

Within this setting, the protean queer performer Ody Icons walks alone (or almost alone at times) and sings, accompanied by Alexandros Avdeliotis on piano, songs about love, memory, absence, and its representation. At moments, you are reminded of Manos Hadjidakis’ “Songs of Sin” or “The Great Erotic”. But mostly, you reflect on the similarities and differences between the poet’s era and ours, a century later.

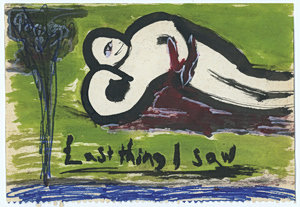

As I listened to these Lapathiotis poems (homosexual poems, written at a time when such language was illegal—often coded as a result), now presented openly in a queer theatrical form, I thought about the power of persistence that we call art.

The technology of this persistence: which not only creates but ultimately enforces forbidden languages, communal languages, forgotten languages, hidden languages. That was the language of queer desire in Lapathiotis’ time. He even developed his own methods of reference—rarely indicating the gender of the lovers in his poems—but simultaneously, often through his strong presence and audacity, he essentially guided the audience on how to read them. This is why seemingly “innocuous” poems caused reactions.

When his poem “Episode” was published, it caused a scandal. The poem reads: “Tall, slender, crazy for caresses / works in a shop / I took him one Saturday night / and we slept together.”

The Metaxas censorship intervened. Lapathiotis sent a now-legendary letter to the committee, mocking them. He suggested that if the content shocked them so much, they could simply change the last line:

“I took him one Saturday night / but we did not lie together!”

I listened to the wonderful Ody Icons, earrings like tears on his cheeks, singing Lapathiotis’ verses to the audience, and I thought about how much pain, desire, effort, intergenerational collaboration, and struggle were necessary for innuendo to become affirmation—how much persistence was required so that the line “but we did not lie together…” no longer needed to be spoken.

You might think this is a strange connection, but I thought of all this when I learned about the mayor of Florina who demanded that the brave Banda Entopica stop playing while singing in Slavo-Macedonian.

As Seferis said, “Centuries of poison; generations of poison.” You might think we have earned the right to speak and sing freely—but the battles must be fought again. Yet I thought, the mayor knows something. He fears rightly, as he sees how power is ultimately defeated—how “cut tongues” return and take revenge.

Not because a band decided to play songs banned for decades in front of him, but because it showed him that no matter how much he shouts or censors, no matter how he stops one song, another will come, and then another. Somewhere, children are already crafting, perhaps in basements, boats, or ruins, how they will one day stand on a stage and articulate minority languages, memories, and forms that were forbidden or are still forbidden. With that thought of these children, let 2026 begin.

Dimitris Papanikolaou is Professor of Modern Greek and Cultural Studies at the University of Oxford.