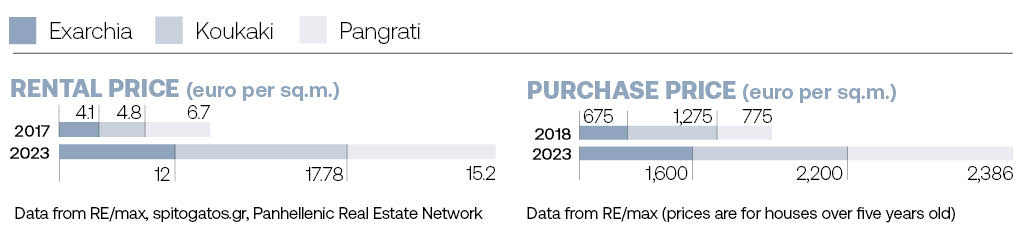

Koukaki, Mets, Pangrati, Psirri, Metaxourgio, Exarchia: Athens neighborhoods that are changing. The development of public transport and the building stock, coupled with high concentrations of bars, eateries and nightspots, have made these areas showcases for an emerging Athens. But the changes are not limited to the facilities on offer. Areas that were traditionally neighborhoods are losing their identities along with their permanent residents. The rise in the value of land in Athens, combined with increasing demand for properties for short-term lets and the subsequent reduction in the number of properties available for long-term rental, is forcing out those who cannot afford the rising rents.

The visitors who are changing Athens’ neighborhoods

Speaking to TO VIMA, Professor Emeritus of Social Geography Thomas Maloutas of Harokopio University confirms that “the changes are due to an increase in ‘imported’ demand—from tourists, digital nomads and occasional visitors. This changes the human geography of housing, but of services, too.” Different-style shops are replacing the traditional ones that used to cater to residents, with the goods on offer usually being more expensive.

Of course, all of this doesn’t only affect tenants; and while the landlords also see their property “going up,” their daily lives are also becoming more expensive. “The grocers and the green grocers of old are gone. In their place, mini-markets are opening up with packaged food at twice the price. If someone opens a luxury bakery selling bread at 3.5 euros a loaf, it will obviously be more profitable for them, but it won’t help improve the daily lives of permanent residents,” notes Costis Hadjimichalis, Professor Emeritus of Geography at Harokopio.

“The center is hemorrhaging”

As he says, “the center is hemorrhaging.” “The permanent residents are leaving and it’s becoming a tourist area. That is, the departing residents leave empty apartments behind, and these become properties for short-term rental. Entire old blocks are being converted into hotels.” A major upheaval in land use is underway, especially in Psirri and Metaxourgio where large industrial sites are being converted into “entertainment centers,” which become another factor pushing old-time residents to leave. And those who left Koukaki or Pangrati, he says, have headed to Kypseli, but this has pushed rents up in a neighborhood which was once known for its affordability and which served as a “refuge” for middle- and low-income tenants.

A lasting change

However, the phenomenon has deep roots, as Costis Hadjimichalis notes. “We should look back to the city planning of the 1980s and 1990s, which provided for the decentralization of services and ministries. This entailed a sudden exodus of thousands of workers who had lived in downtown areas and consumed the goods and services of local businesses there. This hit the city center economy and had a dramatic impact on employment. Then there is suburbanization, another long-standing trend. More affluent families—especially those with children—are gradually leaving the center and seeking housing in neighborhoods with green and open spaces.”

According to the professor, suburbanization had already led to a lot of apartments in the center being left vacant as early as the 1990s: “In the 2000s, immigrants moved into them. Later, they became an attractive destination for real estate investments. And then along come the Golden Visa-style policies, and the short-term rental legislation, which have driven up prices sharply.”

Housing as an investment product

Thomas Maloutas notes that the low prices created by the decade-long financial crisis prepared the ground for foreign investors to convert Athenian housing into money-making ventures: “The sharp rise in tourist numbers created new demand, which made the recession-deflated property prices very attractive to foreign investors. As a result, housing has been transformed from a utility into an investment product, pushing people on low incomes into precarious conditions.”

“As a result, we have a two-pronged problem in the center: on the one hand, there are no permanent residents, while on the other hand the few houses available for rent or purchase are very expensive. While this whole package may be called gentrification, it actually entails forcing permanent residents out and changing the use to which the land is put,” Costis Hadjimichalis stresses.

Short-term gains, long-term decline

These investment initiatives provide the economy with short-term gains, but they constitute a long-term loss. The changes in the center will rob it of its distinctive character. “Because it was actually this diverse and varied land that made Athens attractive. Meaning you’d find a body shop next to a souvlaki joint, with a furniture repairer a few doors down and a linen shop opposite. These shops are closing and the center is turning into an endless line of places to eat, drink and go out—there’s not one business that doesn’t have tables outside.”

Costis Hadjimichalis believes that once these cease to be profitable, the city will fill with boarded-up buildings: “Many hotels and Airbnb are owned by foreign investors who have moved in for a quick profit. When they’re no longer profitable, they’ll just pack up and leave. Then the center of Athens will be left with empty hotels and luxury flats…”

Housing as a safe deposit box

Thomas Maloutas also notes that Athens’ seaside boroughs have witnessed a good deal of change over the last decade, especially the strip from Glyfada to Vouliagmeni, where luxury houses have sprung up which share the same aesthetic and same price— in millions of euros. “These are investment products; their owners aren’t planning on using them to generate income. Rather, they are investing in a stable asset in a market that remains relatively cheap in international terms. They’re not interested in renting them out. Even if they keep them shut up, it’s like they’ve put their money in a safe deposit box,” the professor concludes.