The Polytechnic uprising ended in the early hours of Saturday, as the sun rose over Athens, but it had begun on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 14, with an unprepared student march.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 14

Divided into groups, the “300 provocateurs” were heading from the Law School to the Polytechnic and were later blamed by the regime for the events that culminated in the military intervention of November 17. The first wave of tension was triggered by unverified information that incidents had broken out at the Polytechnic. At the same time, ongoing debates were taking place about how to conduct elections at university faculties, since a year earlier the regime had tried to manipulate them and appoint administrations, while a few months later it revoked military deferments for targeted students. Participation was massive; the student movement had grown stronger over the years and was demanding freedoms that had been denied.

The atmosphere at the Polytechnic that day was relatively calm, but the arrival of students from the Law School undoubtedly influenced the course of events. Small clashes between students and police quickly led to the idea of occupying the university. It was not an idea that immediately found strong supporters. The decision of the Polytechnic faculties was for a boycott until Monday (November 19), not an occupation. They wanted to express their opposition in a measured way. The most active student groups of the time (ANTI-EFEE, Rigas Feraios) believed that conditions were not right for a direct confrontation with the dictatorship, unlike some leftist groups advocating a full frontal plan.

The Architects supported the Polytechnic occupation in the relevant votes. The other faculties voted for abstention, while the Mechanical Engineers delayed making a decision. This political confrontation eventually spilled from the classrooms into the courtyard. Some accused others of irresponsibility and adventurism, while others accused their peers of reformism—i.e., a tendency to abandon the revolution. At that moment, it is estimated that more than 2,000 students were in the Polytechnic.

While the disputes continued, the prosecutor Giorgos Samitas’ order to disperse the students tilted the balance. Discussions about locking and securing the space, out of fear of police violence (as had happened in February 1973), multiplied. Some students forcibly took the keys from the person responsible and began locking the doors. The act was initially spontaneous, and the official decision for occupation came afterward.

The first door to be locked was the one on Tositsa Street. The lock, however, was stuck and the key would not turn. A 15-year-old construction worker, Nikos Artavanis, who had walked from Drapetsona to the Polytechnic—like hundreds of other citizens who were arriving to show support after the first reports—solved the problem by bending an iron rod, signaling the start of the occupation. Rector Konstantinos Konofagos did not consent to the breach of university asylum, and the Polytechnic occupation was formalized despite the temporary departure of a small group of students, mainly Mechanical and Electrical Engineers who initially disagreed but eventually returned to support the others, while the regime hesitated over the method to enforce.

It became clear that the authorities had underestimated developments, resulting in a growing wave of resistance with more students joining the occupation. For example, about 1,000 students from the School of Industrial Studies entered after 6 p.m. Despite factional differences, a sense of unity and solidarity developed. All agreed on the need for self-organization. Some, more revolutionary, took initiatives outside the central line. Molotov cocktails were even being made in workshops. Meanwhile, kitchens and a dining hall were organized, and classrooms were converted into sleeping quarters.

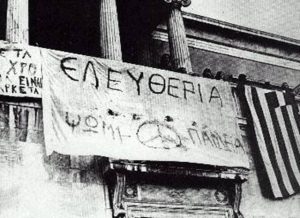

While the main gate remained open, passage was free. Students stopped trolleys to write slogans or distribute leaflets, drivers honked, people showed support, and traffic on Patission Street moved with difficulty. The walls began to fill with anti-regime slogans in spray paint, paint, and markers; an emblem with the phoenix and soldier, the junta’s symbol, was destroyed in public view. Efforts to operate a radio station also began, a pivotal point for spreading the message of resistance.

By around 11:30 p.m. on Wednesday, the main gate was locked. Inside were approximately 2,500 students, organized or independent. There was no turning back.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 15

On Thursday, November 15, more people began gathering at the Polytechnic. Police set up a cordon to block the occupiers’ contact with the outside, but the crowd broke through. From noon, the students’ radio station began broadcasting, decisively contributing to the mass mobilization of the demonstrations.

The occupation was now established; no faculty had serious objections. The proposal for a heroic exit received very little support. A new Coordinating Committee was elected, including members from all student factions. Popular support grew, and soon workers, construction laborers, and students arrived at the Polytechnic. Estimates put the total number of citizens inside or outside at 20,000. On Thursday evening, a concert was organized in the assembly hall with Giannis Markopoulos, Nikos Xylouris, and Maria Dimitriadi. No one slept the second night either.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16

From morning to afternoon on Friday, November 16, the atmosphere was almost festive. Euphoria and uplift prevailed over fear and anxiety. The uprising’s momentum had grown enormously. Students continually gained new allies, while the political world expressed support for events inside and outside the Polytechnic.

Until sunset, there was a feeling that the junta would fall this time. The University Senate held firm, insisting on maintaining asylum. However, the military government had begun to worry about the scale of the protests, and discussions behind closed doors intensified. The cabinet convened an emergency session to assess the situation. Dictator Papadopoulos was furious with the government’s handling and demanded evacuation and street closures. He could not believe how much the wave of resistance had spread, threatening the regime.

At noon, approximately 500 farmers from Megara, who had previously gathered outside the Supreme Court to protest land expropriations for a refinery, arrived at the Polytechnic. For a few hours, the alliance “farmers-workers-students” became a reality, with the historic institution at the center of resistance. The dictatorship decided to act decisively. It did not want to risk a bloody confrontation but aimed to de-escalate and normalize the situation by any means. Yet controlling such a massive wave without tear gas, violence, and authoritarian measures was difficult.

As shops closed, the crowd at the Polytechnic grew. The Coordinating Committee held a press conference, inviting journalists. The students’ goal was now to overthrow the junta and form a government of national unity. Some wanted to swear it in at the courtyard. Coordination among factions was problematic for several hours until they agreed on a common text. The press conference took place at 3:30 p.m., with 20 journalists present. No photographs or questions were allowed; only the declaration was read. Student Tonia Moropoulou read it aloud but skipped the last sentence due to factional disagreement. No one wanted to jeopardize the effort; all conceded when necessary. Regardless of objections, this declaration remains the only written text of the three-day occupation. A few hours later, the final paragraph was broadcast by Stelios Logothetis via the radio station.

By Friday afternoon, Athens had become a battlefield. Demonstrations in various parts of the capital were coordinated with the Polytechnic’s live pulse. The first public building targeted was the Prefecture at Chaftia. The General Police Directorate and then the OTE followed. Police tear gas was widespread, making it hard for protesters to breathe. Many sought medical help for the trapped students. Appeals for medicine, oxygen, and staff were made via the radio station.

Within two hours, the atmosphere had dramatically changed, and the regime went on the offensive. Stray bullets whistled through the air. Under the new conditions, there was a sense that students were at risk even from political parties (KKE, KKE Interior), and efforts were made to evacuate members, but it was too late. With the situation out of control, Georgios Papadopoulos ordered military intervention. Lawyer Spyridon Kontomaris, a former Union of the Centre MP, died of a heart attack due to the chemicals used. From the Polytechnic loudspeakers, the Coordinating Committee urged anyone leaving to do so immediately, as conditions would worsen. The cordon tightened.

Curfew in the center was the next government measure. Snipers, mainly from the Ministry of Public Order, shot indiscriminately, targeting mainly those outside the Polytechnic. A bullet from Ministry guards killed 17-year-old student Diomidis Komninos, who was carrying the injured inside.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 17

The Coordinating Committee tried to manage the unexpected situation. Surgical teams were organized for the seriously wounded. Student George Samouris, 22, was shot dead by police at the intersection of Kallidromeiou and Zosimadon streets.

Via the radio station, Dimitris Papachristos announced: “Greeks are killing Greeks.” Among the victims was a Norwegian, Toril Margrete Engeland, next to 26-year-old Vasilis Famellos, who was participating in the demonstrations. At midnight, the first armored vehicles appeared, moving along Vasilissis Sofias and Panepistimiou streets. Attempts at political intervention by ERE President Panagiotis Kanellopoulos and former Minister Georgios Mavros failed—they did not even approach the Polytechnic. The surrounding streets were empty; the regime had successfully isolated students and others inside. Coordinating Committee members reconvened in the Architecture School to finalize negotiation terms. Students Kyriakos Stamelos and Kostas Laliotis took on this demanding task, while others armed themselves with makeshift weapons such as stilts, chairs, and other objects. They had to defend themselves.

Shortly before 2:00 a.m., tanks arrived and parked outside, encircling the Polytechnic. Dimitris Papachristos appealed to the soldiers not to follow orders and recited the National Anthem. The floodlights came on, and the countdown had begun.

Against the superficial and highly artificial liberalization being promoted by the self-appointed President of the Republic, Georgios Papadopoulos, in the early hours of November 17, the junta removed its mask and revealed its ruthless face. Violence was the final instrument of authoritarian control in a society boiling for democracy. The order for tanks to storm the Polytechnic marked in bold, blood-red letters a long period of obliterating every minor and major human right, which had begun six and a half years earlier, on April 21, 1967.