Mr. Andreas has his table. He arrives every morning at 8:30 sharp. He’s always dressed in a suit, a pocket square tucked neatly at his lapel — as if he’s stepped out of a Greece from another era. Yannis, the waiter, brings him his usual without a single word exchanged: a Greek coffee, lightly sweetened. “I remember every customer’s coffee order,” Yannis jokes. “How could I forget Mr. Andreas? He’s practically part of the furniture.”

At the next table, young mothers with strollers trade worries. Across from them, a group of girls with long eyelashes and elaborate nails sit silently, eyes glued to their phones. Mr. Andreas scans the room for someone to talk to, but no one looks up.

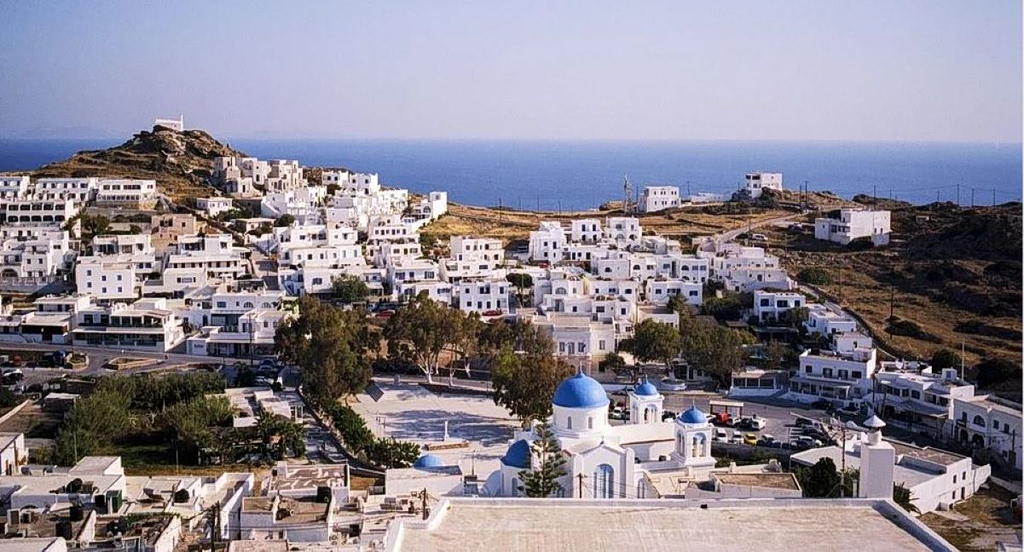

A man and a woman drink coffee in the Monastiraki district of Athens,with the ancient Acropolis hill in the background, Monday, May 3, 2021. (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris)

A model with “clay feet”

By now the café has filled up — groups of friends, loners, people grabbing their coffee to go on their way to work. It’s easy to wonder whether any other European country drinks as much coffee as Greece. Italy might come to mind, but in Greece coffee isn’t just a drink; it’s a ritual. It’s the pleasure of the first sip, the meeting point for friends, the energy that starts your day.

And so the city filled with cafés. From the traditional kafeneio in the main square to every side street, suddenly each corner has its own version — different styles, different vibes, little jewels scattered across the map.

A recent London School of Economics (LSE) study noted that post-bailout Greece has effectively transformed into a “Coffee Economy.” But the report sounds an alarm: the country’s growth model is built on the food-and-beverage sector and low wages, trapping Greece in a cycle of low productivity and social insecurity.

According to the LSE findings, Greece has become stuck in a development model with “clay feet.” In simple terms: investment in innovation and high-value sectors is scarce, while the economy leans on low-productivity businesses that appear to fuel growth but weaken the country’s long-term foundations.

The model is often described with catchy names: “the coffee economy” or even “the waiter economy.” Cheap labor — often uninsured — absorbed into jobs with squeezed wages and little hope for long-term prosperity.

So why do Greek entrepreneurs keep opening cafés?

What pushes so many Greeks to invest in a small (or large) café rather than pursue something else? And who are the workers who keep this ecosystem running?

Giannis Chatzialexis, owner of a café in Piraeus located in a charming arcade linking Iroon Polytechneiou and Platonos Street, has a simple answer:

“Small cafés mean lower operating costs — and that means you’re less likely to go under. Lower costs mean fewer employees, cheaper rent, smaller fees. Everything is connected. And most small cafés are family businesses. You don’t need to hire a manager or extra staff; family members can cover the shifts.”

Nikos Grentzelos, vice-president of the Athens Chamber of Tradesmen, agrees:

“Entrepreneurs see cafés as an easy investment that can create jobs for family members. Cafés have daily cash flow. And you don’t need advanced knowledge — just a few seminars.”

Behind the counter

Thanos works in a café in Nea Smyrni. When we meet him, he and his colleagues are decorating the shop’s Christmas tree. He’s an athlete; when he’s not training, he serves coffee and drinks. On his days off, he attends classes at the Gymnastics Academy where he studies.

“Waiting tables isn’t something permanent for me,” he says. “It’s just to make some pocket money so I don’t have to ask my parents. I share an apartment, but rent is high. Two years ago, I earned 4 euros an hour. Now I get 6. In some places it’s still 5. We used to work four days a week but only get declared for two. With the new digital work-card system, that’s no longer possible.”

A colleague calls out from across the shop:

“Tell her about the tips!”

Thanos sighs. Since tips became taxed and more payments are made through cards, gratuities have dropped dramatically — and so has the extra income they once relied upon.

His girlfriend, listening in, jumps in:

“I drink at least two coffees a day. If I bought them all take-away, I’d spend nearly 2,000 euros a month with how expensive coffee has gotten!”

And she’s not alone. Many customers wonder the same thing: with every price hike, coffee starts to feel like a luxury. But then comes the other thought — are we really going to cut back on coffee too?

Photo by Maro Kouri for To Vima.

A working reality built on coffee

Small family cafés, low operating costs, daily liquidity, easily acquired skills. It sounds like an accessible model. But the Chamber’s data adds a reality check: the average lifespan of a small café is just 18 to 20 months — less than two years.

In other words: even this supposedly “easy” business move demands professionalism and consistency to survive.

Because in Greece’s “coffee economy,” the math may look simple — but the foundations remain undeniably fragile.

We would like to thank Ark Cafe for hosting To Vima.com.