When I first read The Guardian’s description of a Swedish school morning at Mariebergsskolan in Karlstad, I stared in disbelief. The article described a bistro-style cafeteria with cream-colored walls, where students could start their day with a ginger-and-lemon juice shot, golden milk or even overnight oats with caramelized milk from the… energy bar. Even more astonishingly, the paper reported that “all the ingredients were donated by local supermarkets which were giving away surplus fruit and vegetables to minimize food waste.”

The scene felt so orderly, so alien to my own memories of school canteens, that it bordered on science fiction. Yet it was real, a product of Sweden’s longstanding commitment to healthy food and sustainability.

Sweden’s universal free school-meal program serves nearly 2 million meals per day. School lunches have been guaranteed as a right since 1946 and legally required to be nutritious since 2011. Even so, the system has not escaped self-scrutiny. The Guardian reports that in 2018, the Swedish Food Agency warned that school meals weren’t doing enough to support healthy eating or sustainability. What followed was a national effort, led by Sweden’s innovation agency, Vinnova, to rethink not only the food but the entire experience of eating at school. That effort produced the pilot program at Mariebergsskolan in Karlstad.

Reading about those juice shots, I couldn’t help thinking of my own school canteen in Greece in the 1990s. It was, to put it politely, not Sweden.

Greece: The Canteen of Memory

I still remember the thrill of buying one precious piece of pink Turkish delight from the tiny school canteen. It came wrapped in a delicate piece of paper, dusted with sugar. When I opened it, a small army of ants had beaten me to the prize.

That was Greece in the ’90s: where “healthy” at the school canteen meant a banana, or a koulouri with a slice of graviera cheese. More often, if you were lucky enough to buy lunch instead of bringing it from home, you chose a peinirli or a slice of pizza, the ham and cheese stiffened at the edges after hours under fluorescent lights. It was a world that felt normal back then, but now reads like a caricature of a country still learning how to nourish its young.

At the time, there was no coherent nutritional framework in schools. Parents worried less about ultra-processed foods or added sugars. Nothing in my childhood canteen suggested that the school or the state had thought deeply about what a growing child needed to build healthy eating habits. But as our understanding of childhood nutrition evolved, the approach to school lunches changed fundamentally.

Why School Meals Matter

Anyone who has tried to feed a child knows that mealtimes can turn, without warning, into a battleground: one more bite, one less complaint, a piece of banana peeled the wrong way or not peeled at all, the wrong texture, color, shape or size that can trigger a full-on tantrum. Schools, however, occupy a different and often underestimated space in a child’s relationship with food. Given the right conditions, lunch at school can succeed where many exasperated parents fail. It can help foster community, establish routines and gently encourage children to explore.

But the importance of school meals goes far beyond exposure to broccoli. In many parts of the world, school is the only place where a child can count on a nutritious meal. As a WHO report notes, for vulnerable families “school feeding programs are not only a vital safety net but also a lifeline that protects their children’s health, supports their learning, and strengthens social protection systems.” Research has shown time and time again that school meals are among the most effective interventions for improving academic outcomes, reducing dropout rates, and breaking cycles of poverty.

There is nothing theoretical about the need for such protection. According to Eurostat data for 2024, 11.3 percent of Greek households can afford a proper meal only every other day, placing Greece among the five most food-insecure countries in the European Union. And while hunger is one part of the story, childhood obesity is the other.

Maria Hassapidou, professor of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics and Greece’s national coordinator for the WHO’s Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI), has spent more than three decades studying childhood obesity. She notes that the link between poverty and childhood obesity has been documented again and again in national and international studies and is painfully visible in Greek households.

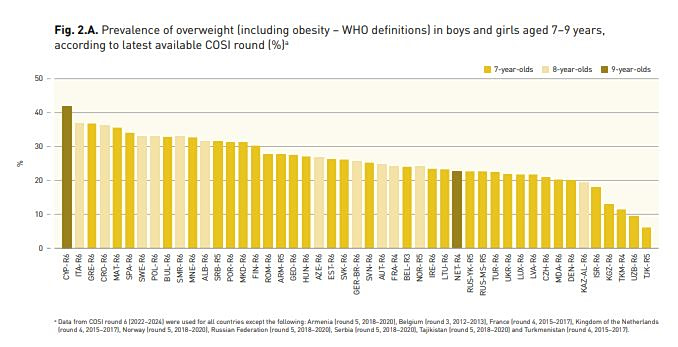

“In 2010, Greece had the highest rate of childhood obesity in Europe, and it shook us,” she told To Vima International Edition. “Today, we are one of the countries that has shown significant improvement. The rates are still very high,” she added, “but the reduction is real.”

According to the latest COSI survey (2022–24), Greece still ranks among the countries with the highest childhood overweight and obesity levels in Europe: more than a third of 7-year-olds are overweight, and nearly one in five is obese. By age 9, the numbers climb further still. Only 16 percent of Greek children eat vegetables daily—the lowest rate among 31 nations surveyed.

And yet, Greece is also one of only four countries, along with Spain, Italy and Israel, to show a statistically significant decline in the prevalence of overweight children in recent years. It is, Hassapidou notes, a meaningful shift, and one that suggests policy initiatives, parental awareness and everyday school routines can change the trajectory.

Part of that shift, she believes, comes from a new generation of parents who are far better informed than their predecessors. “Parents today know a lot more than we did. The average Greek mother now understands that her child shouldn’t be overweight, while that wasn’t the case 30 years ago. Indeed, even among health professionals, many failed to fully grasp the magnitude of the problem back then.” But the biggest change, in her view, is structural.

The New Greek School Meal: A Social Contract

Since its pilot launch in 2016 in just nine schools, the Greek School Meals program has expanded dramatically. According to data provided by the Organization of Welfare Benefits and Social Solidarity (OPEKA), for the current academic year, it will serve 231,062 warm meals daily across 1,918 school units in 153 municipalities, with a budget of €114.9 million. Meals are cooked fresh each day using the Cook & Serve method, with no freezing or long-term storage.

The program is not merely about feeding children; it is a social-protection measure. Municipalities are selected through a multi-criteria model prioritizing regions with high child poverty, unemployment and low incomes; poignantly, the traditionally prosperous agricultural areas of Thessaly devastated by Storm Daniel are included. The goal is simple: to support vulnerable families, promote equal educational opportunities, and ensure no child has to sit through a lesson hungry.

But over and beyond these warm lunches, Greek schools have undergone a quieter transformation, one unimaginable in the anything-goes tuck-shops of the 1990s. Today, almost every school has a canteen, and the rules governing what can be sold have tightened dramatically. Gone are the mystery pies and sugar-dusted treats of my childhood. In their place, a curated list of seasonal fruit, vegetable salads, whole-meal Greek sesame bagels and crackers, plain yogurt, simple sandwiches with cheese or turkey, and even freshly blended fruit smoothies. Pies and pizzas still exist but now conform to strict nutritional standards. Chocolate appears only in miniature portions, and soft drinks are banned outright.

A Greek National Action Plan Against Obesity

For the first time, Greece is also implementing operating a National Action Plan Against Childhood Obesity, a unified strategy Hassapidou describes as the most coordinated effort she has seen in her career. The plan spans the full spectrum of prevention: early-childhood education via the Food for Action program; online consultations with dietitians for families who need guidance; and specialized pediatric obesity clinics in health centers and hospitals. Its national target is clear: a 10% reduction in childhood obesity by 2030. Hassapidou also credits the long prelude to the current progress: more than a decade of EU-funded initiatives–JANPA, Big O, ENERGY, ToyBox, DigiCare4You, Feel4Diabetes–whose cumulative effect, she believes, helped Greece step back from the top of Europe’s obesity rankings. “We’re not where we need to be,” she said, “but we’re no longer where we were.”

Spain: A Classroom, a Snack, a Small Transformation

Spain’s approach differs from Greece and Sweden, and is anchored in the concept of the comedor found in every primary school and kindergarten across the country. El comedor is more than a cafeteria, it’s a daily ritual: a sit-down hot lunch eaten around 1 p.m. In the public system, it costs about €5.50 a day, with subsidies for families who need them. Children are served a vegetable-based starter, a main dish, and fruit or yogurt for dessert, eating together under the watchful eye of young monitors. The meal becomes as much a social education as a nutritional one.

In my daughter’s class, the teacher was warned early on that several children did not eat fruit or vegetables “in any shape or form.” Still, she persevered: all students enrolled in the comedor would eat lunch together.

Furthermore, in this particular school, each day one child was also responsible for bringing a healthy morning snack for the entire class. Most days, aside from birthdays, only fruit or vegetables were allowed–hummus with carrots, maybe, or rice cakes. For younger children, this rotating responsibility was pure enchantment. Parents whispered about the cost, but for a class of 19 children, buying a round of apples or mandarins once or twice a month rarely strained anyone’s budget. By year’s end, the transformation was unmistakable: children who once recoiled from anything green were eating broccoli, lentil stews or green beans for lunch.

Spain’s comedor is also a vast safety net. In Madrid, 119,000 students were accepted into the school-meal grant system for 2025–26. Yet the net does not always hold. El País reported that many families had been excluded due to income-threshold inconsistencies or administrative errors, despite the budget remaining unchanged at €68 million. A 2025 inspection found that a third of school cafeterias lacked accredited nutritionists, and another third offered too few vegetables and too many fried or pre-cooked foods.

Spain’s system can be transformative but uneven, shaped by region, budget and political will. Still, for our school class, the comedor was a small miracle. It turned fruit-averse toddlers into children who reached eagerly for the mandarins.

If the school canteen is a mirror, Europe’s reflection is uneven but dynamic. It reflects our changing attitudes towards food as a transformational policy tool with the power to create a more healthy, sustainable and equal society.

Because the meaning of a school meal transcends nutrition. As sociologist Gary Alan Fine wrote: “Food reveals our souls… The connection between identity and consumption gives food a central role in the creation of community.” A school meal, then, is a civic gesture, a daily promise a society makes to its children about who they are and what they deserve.