Fifteen people lost their lives on the night of February 3, when the small vessel they were traveling in collided with a Hellenic Coast Guard patrol boat off the coast of Chios. For an island that has stood on the front lines of Europe’s migration routes for more than a decade, the aftermath felt painfully familiar.

The inflatable boat, approximately eight meters long, was carrying roughly forty migrants and refugees. Of them, only twenty-four were rescued. According to the official Coast Guard account, one of its vessels was “conducting a scheduled patrol” when it detected a speedboat “operating without navigation lights and heading toward the eastern coast of Chios.” The authorities allege that the operator ignored light and sound signals, attempted to flee and rammed the patrol vessel, causing the migrant boat to capsize. Doctors at Chios General Hospital later described the injuries they encountered as resembling those seen in “a fatal multi-vehicle car accident.”

The government expressed condolences for the dead while praising the Coast Guard’s actions. Ministers and ruling-party MPs attributed responsibility solely to the “murderous traffickers” who exploit desperate people and overcrowd unseaworthy boats. The opposition, almost unanimously, called for a full and transparent investigation.

Immigration Minister Thanos Plevris accused critics of siding with smugglers. “I believe the Coast Guard report,” he said. “You can believe the smugglers,” he told opposition MPs pointedly. In a recent interview, he went even further. “The Left went to the scene (of the shipwreck) not because they cared what happened to the victims, but rather with the sole aim of slandering the men and women of the Coast Guard in order to score political points.”

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis struck a more measured tone. In an interview with Foreign Policy, he called the incident a tragedy and stressed the need for an investigation. His “preliminary” information, he said, suggested that the Coast Guard vessel had been rammed by a smaller boat. Such situations “happen quite frequently in the Aegean,” he added, noting, “my Coast Guard, we’re not a welcoming committee.”

Yet key elements of the official account remain unverified. Opposition MPs who met survivors have questioned the Coast Guard’s version. The patrol vessel’s onboard camera was not activated. In his testimony, the captain said since visibility was adequate that night, there was no need to turn on the thermal camera. He added: “There is a recording function, but I was not issued a recording card for this vessel by my service. It is not a recording device like a mobile phone camera. It can record, but only if It has been provided with a recording card.”

Graves at a cemetery for refugees and migrants who lost their lives while crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece, on Thursday, May 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris)

Authorities have arrested the sole Moroccan survivor as a suspected smuggler, based on testimony from one passenger. His lawyers say there are “no substantial indications of guilt” and that other pre-trial statements do not identify him as the operator. They allege that witnesses reported “no signal, no warning, no flashing light… only a collision with the Coast Guard vessel.”

The absence of video documentation, and the rapid attribution of criminal responsibility to survivors, closely echo the Pylos shipwreck of June 2023, which the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights described as “one of the deadliest boat disasters in the Mediterranean Sea to date.”

Pylos: a precedent that still looms

After the shipwreck of the Adriana off Pylos, in which over 500 people reportedly perished (though the Greek authorities dispute the number), the Greek Ombudsman opened its own inquiry when the Coast Guard declined to initiate disciplinary proceedings. In a report issued in February 2025, the Ombudsman identified “serious and blameworthy omissions” by senior officers and cited indications of potential criminal liability. Key evidence was unavailable, including communications with the Search and Rescue Coordination Center, which authorities said “were not digitally recorded,” despite there being a legal requirement to do so. Footage from the patrol vessel’s onboard cameras was also missing, with the Coast Guard claiming the system had been “out of operation due to malfunction,” a decisive absence which made it impossible to properly assess responsibility.

A legal framework Greece is bound by

The legal framework governing maritime operations is clear: international human rights law and the law of the sea require states to prioritize the protection of life. In addition, the principle of non-refoulement, a cornerstone of refugee protection, prohibits the removal of persons to a country where their life or liberty would be at risk.

Minos Mouzourakis, Legal and Advocacy Officer at Refugee Support Aegean, told TO BHMA International Edition:“The paramount need to safeguard lives at sea must be the primary consideration of Coast Guard operations according to international and EU rules on human rights and the law of the sea (namely, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, European Convention on Human Rights, SOLAS Convention, Regulation (EU) 656/2014). These also impose a prohibition on collective expulsions and on removing individuals to a place where their life or liberty would be at risk (refoulement).”

Those obligations apply regardless of a person’s migration status. Border enforcement does not displace the duty to rescue or to assess protection claims.

A child looks on as newly-arrived migrants are sheltered in a municipal hall in the town of Agyia, on the island of Crete, Greece, July 11, 2025. REUTERS/Nicolas Economou

Two forms of pushback

The evidence points to two distinct but related practices.

The first involves maritime pushbacks: boats intercepted at sea and allegedly forced back toward Turkish waters, sometimes through aggressive maneuvers, ramming, deliberate engine damage or abandonment on life rafts.

The second involves informal forced returns after migrants have already reached Greek territory. The Greek National Commission for Human Rights defines these as “summary removals of third-country nationals from the territory of a state without proper legal procedures, often involving the use of violence and in violation of international and European human rights law.” They are described as “covert operations by design and intent,” yet “frequently conducted openly,” involving denial of access to asylum procedures, informal detention and removal “without registration, documentation or identification.”

Both practices are illegal under Greek, EU and international law. That either is employed in Greece has been repeatedly and strenuously denied by Greek authorities.

ECHR

In January 2025, the European Court of Human Rights delivered a ruling in A.R.E. v. Greece that marked a highly consequential and significant judicial acknowledgment of evidence pointing to pushbacks by Greek authorities.

The Court found that there were “strong indications” that, at the time of the events examined, a systematic practice of pushbacks of third-country nationals by Greek authorities had existed in the Evros region. The Court also held that the applicant had been returned to Turkey without an individual assessment of the risks she faced, amounting to an unlawful removal without due process.

There has been a series of rulings over the past three years—Safi v. Greece, Alkhatib v. Greece, Almukhlas v. Greece and F.M. v. Greece—where the ECHR has condemned Greece for failures in rescue operations, fatal use of force by Coast Guard officers, and ineffective criminal investigations into maritime incidents.

Documenting a pattern in the Aegean

Allegations of pushbacks have been documented by major news organizations, including the BBC, The New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel, as well as national and international human rights bodies.

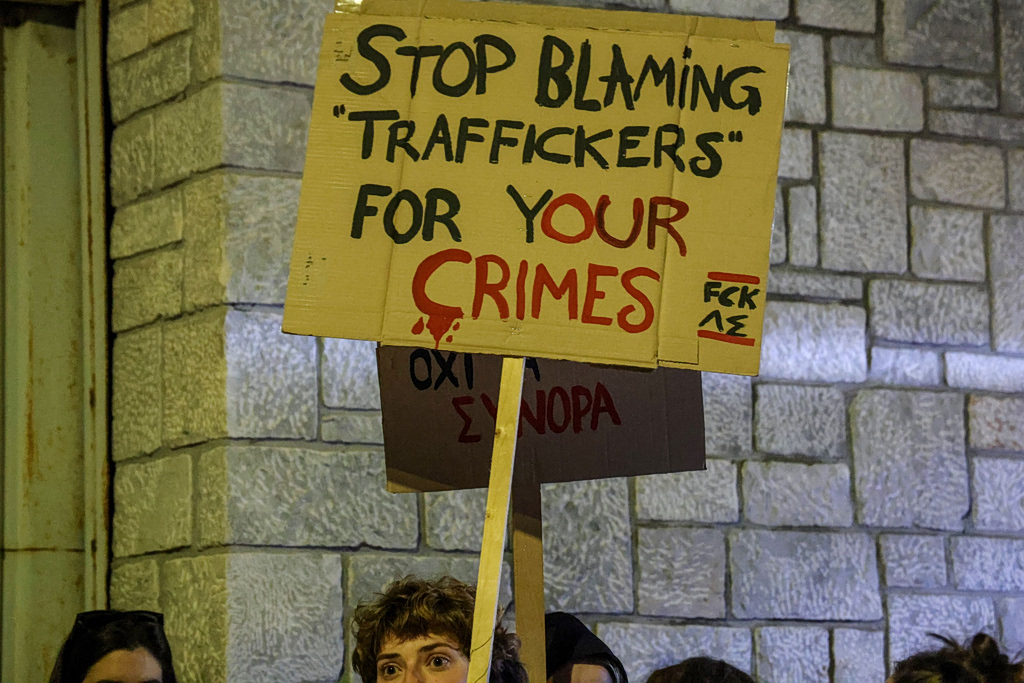

A protester holds a placard during a protest following a migrant boat collision with the coast guard, which left more than a dozen dead, in Chios, Greece, February 4, 2026. REUTERS/Konstantinos Anagnostou

In Greece, the Greek National Commission for Human Rights operates the Recording Mechanism of Informal Forced Returns in cooperation with civil society organizations and with technical support from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In its 2024 cycle, the Mechanism recorded 52 alleged incidents involving at least 1,517 individuals, including 300 women and 225 children. Of the 45 alleged victims whose testimonies were documented, 40 said they had never been registered or identified by Greek authorities, despite being found within Greek territory or under Greek jurisdiction. Of the 45, three were recognized refugees and one a registered asylum seeker.

Even those figures are likely to be incomplete. After visiting Greece in February 2025, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights reported persisting allegations of summary returns at both land and maritime borders. Citing information from UNHCR, he said the agency had received 248 allegations of summary returns in the first half of 2024 alone, 166 of which it assessed as substantiated; the substantiated cases affected at least 4,229 people. The Commissioner noted that the available data almost certainly underestimates the scale of the practice.

Other institutions have reached similar conclusions. The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture said it had received “many consistent and credible allegations” of violent pushbacks across the Evros River and at sea toward Turkey. In its 2024 review of Greece, the United Nations Human Rights Committee expressed grave concern about “multiple reports of pushbacks” at land and sea borders, citing allegations of excessive force, ill-treatment and inadequate procedural safeguards, as well as a lack of systematic investigations.

Greek authorities have consistently rejected the characterization of pushbacks as systemic, maintaining that violent summary returns “do not occur” or represent isolated incidents under previous governments. Some reports have been described by officials as “unjust.”

At the same time, Greece’s own oversight bodies have pointed to weaknesses in internal investigations. In its 2024 annual report, the National Mechanism for the Investigation of Arbitrary Incidents, operating under the Greek Ombudsman, said complaints of alleged pushbacks had continued throughout the year and, for a second consecutive year, maritime allegations had exceeded those at land borders. The Mechanism received seven new cases in 2024—one transmitted by the police and six by the Coast Guard—and noted that maritime inquiries are often opened only following the filing of a Serious Incident Report by Frontex, rather than on the authorities’ own initiative. It identified recurring shortcomings in disciplinary investigations, including delays and deficiencies in evidence gathering.

Mouzourakis said the official statistics reflect those concerns. “Out of over 100 cases treated by the Naval Court Prosecutor concerning push back incidents, none have led to the prosecution of Coast Guard officials. As for disciplinary proceedings conducted by the Coast Guard itself, none of the 42 internal sworn inquiries (EDE) carried out into allegations of human rights violations have led to disciplinary action,” he told TO BHMA International Edition.

In rare instances, visual evidence has surfaced. A video posted publicly in 2024 by an Austrian activist appeared to show a Coast Guard vessel aggressively intercepting a migrant boat, with women and children heard screaming. According to reporting by Balkan Insight, when Frontex Executive Director Hans Leijtens was shown the footage, he acknowledged that the agency’s handling of its cooperation with Greece may have contributed to a “sense of impunity.”

Frontex: warnings ignored, cameras switched off

Internal Frontex documents reveal persistent concern within the agency that has been tasked with supporting EU member states in the management of the bloc’s external borders and “has hundreds of border officers in Greece, as well as boats, cars, mobile surveillance systems, thermal cameras and drones.”

Following the Pylos shipwreck, Frontex’s Fundamental Rights Officer formally advised Executive Director Hans Leijtens to suspend or terminate operations in Greece, citing frequent and serious violations.

Instead, Leijtens pursued what he described as “enhanced cooperation.” In an April 2025 interview with Balkan Insight, he acknowledged that he had recently “grown impatient” with the situation in Greece, criticizing the implementation of agreed measures “in a formalistic manner.” He singled out the use of onboard cameras on Coast Guard vessels as a key example.

As reported at the time, “cameras, for example, were installed on Coast Guard vessels to record potential abuses, but they weren’t turned on.”

“I already told the Greeks: those remaining points are not rocket science. I want them fulfilled before we talk about the next cooperation,” Leijtens said. “If it’s not done, I will not co-finance Greek vessels.”

The same month Frontex announced that it was “reviewing 12 cases of potential human rights violations by Greece.”