WILLMAR, Minn.—Nearly 30 years ago in this small agricultural town, resident Pablo Obregon did a double take at a group waiting for the bus downtown on the first day of school. They were Somali children.

“Where did they come from?” he recalls wondering. Obregon, now Willmar’s director of community growth, is no longer surprised when he sees large numbers of Somalis.

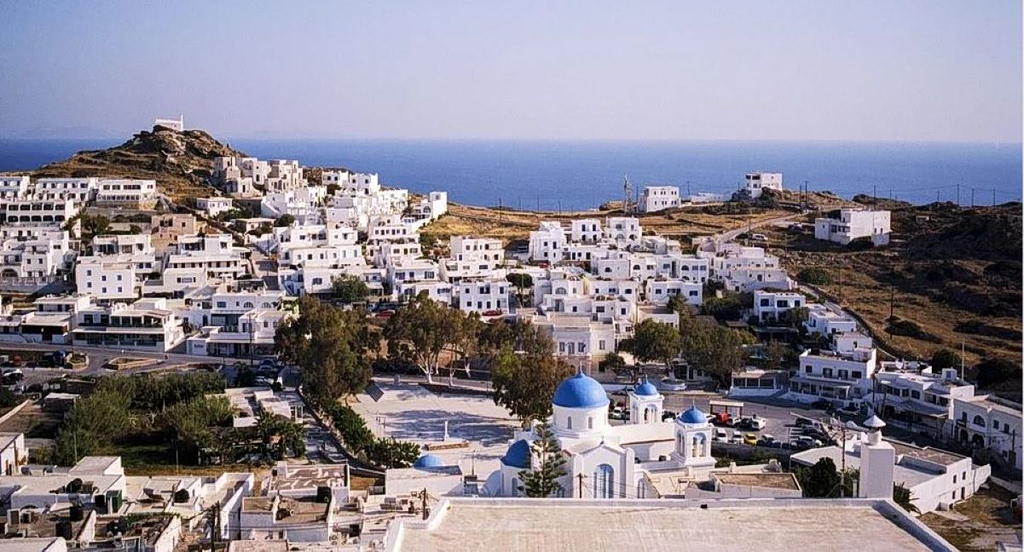

So many have settled here that a lively stretch downtown is called Little Mogadishu because Somalis run more than a dozen storefront businesses. In winter it isn’t uncommon to see Somalis in traditional dress bundled up in big American-style parkas and stocking caps worn over hijabs. Somalis represent about a quarter of production workers at the Jennie-O turkey plant, the economic engine of this community of nearly 22,000 some 95 miles west of Minneapolis.

But in recent days, downtown’s strip of restaurants, groceries and clothing stores has been attracting only a few customers, shopkeepers say. ICE raids are ramping up in Minnesota, and President Trump has lashed out against immigrants from Somalia, calling them “garbage” and saying he doesn’t want them in the U.S.

Abdiweli Yusuf owns a grocery store in Willmar with family members. /Photography by Yasmin Yassin for WSJ

Photography by Yasmin Yassin for WSJ

“They are not willing to go to work and not coming outside a lot because of fear,” said Abdiweli Yusuf , a 33-year-old Somali-American, as he swept up the grocery store he owns with family members. He wore a traditional robe-like khamiis under a long wool coat and a pink stocking cap against the below-zero windchill, which he didn’t seem to mind. “Minnesota is the most welcoming place in America,” he said. “I have five kids who were born here in Willmar hospitals. This is our forever home.”

Many here, and across Minnesota, have been shaken by a sprawling fraud scandal that has put the state’s Somali community in the national spotlight and drawn Trump’s ire. Federal prosecutors say dozens of people bilked taxpayers by setting up scam social-services companies. It has hit home here.

A Minneapolis man pleaded guilty in February to fraud that included using the address of a Willmar restaurant to claim that he fed 1.6 million meals to children early in the pandemic, according to the U.S. Attorney for the District of Minnesota.

Local leaders say the scandal doesn’t reflect the Somali community broadly. “I can honestly say I haven’t encountered any bad Somalis,” said Willmar Mayor Doug Reese. “I mean, there’s probably some, but by and large, they’re good people.”

When Reese, a former union official, moved to the area in 1972, the city was made up mostly of descendants of Swedes, Norwegians, Dutch and Germans, he said.

The first big wave of more recent migrants was Hispanic farmworkers.

Rollie Nissen , a 79-year-old former shoe salesman and longtime Republican leader in the area, said he appreciated the inflow of cash from the newcomers. “I had no problem with them, because when they got paid they would come to my store and buy cowboy boots,” he said.

Nissen did express reservations, however, after the Somalis started to arrive in relatively large numbers.

In 2019, after Trump issued an executive order requiring states and counties to formally consent to continue receiving refugees, Kandiyohi County—where Willmar is the county seat—wrestled with the decision. Nissen, then chair of the county board, said many people wanted a pause in refugees but were afraid to say so out of fear of being labeled racist. He cited concerns from constituents about overburdened social services in the area, according to local radio coverage of the meeting.

In the end, the county became the first in Minnesota to say they wanted to continue, but only in a 3-to-2 vote. Nissen was one of two “no” votes.

Today, Nissen said he has a very good Somali friend and drives Somali children to school in his part-time job as a bus driver. He feels the president’s comments go too far.

“It’s not just the Somalis who are raiding the bank,” he said. “It’s a broad brush, I don’t think he should be painting with a broad brush. We should get rid of the people who are here illegally, not ship everybody back to Somalia or Mexico or Venezuela.”

The Somalis arriving in the past few decades have changed the face of downtown, renting apartments and opening businesses in the storefronts. Some display colorful clothing and rugs, and many of the restaurants serve a traditional Somali spiced tea with steamed milk and lots of sugar. “They are very entrepreneurial,” said Obregon, Willmar’s community-growth director.

Now Hispanic and Somali children make up the majority of children in the local school.

Vicki Davis, a city council member and parateacher in special education, said her first-grade class of 22 students has only four white children, including one Ukrainian.

“It’s fun to see them play together,” she said. “One of the Somali girls’ hijabs will fall off and all of the girls are like, ‘Oh, my goodness, let’s help her.’ It’s just really sweet.”

Sending Somalis out of the country would be a blow to Willmar’s economy, officials said.

“Well, first thing I think of is Jennie-O,” said Mayor Reese. “They aren’t going to have the workers, right? And I don’t know where you’d find them.”

Somalis are an important part of the plant’s strong culture, said Hunter Pagel , head of human resources at the plant, which is owned by Hormel Foods. “We would struggle if we didn’t have the team members working on the floor,” he said. “There’s only so much you can automate. There’s something about the human touch—they do a better job.”

A Somali-owned store in Willmar. /Photography by Yasmin Yassin for WSJ

Write to Joe Barrett at Joseph.Barrett@wsj.com