On a recent evening, a trio of Ukrainian drones flew under the cover of darkness to a Russian position and decided among themselves exactly when to strike.

The assault was an example of how Ukraine is using artificial intelligence to allow groups of drones to coordinate with each other to attack Russian positions, an innovative technology that heralds the future of battle.

Military experts say the so-called swarm technology represents the next frontier for drone warfare because of its potential to allow tens or even thousands of drones—or swarms—to be deployed at once to overwhelm the defenses of a target, be that a city or an individual military asset.

Ukraine has conducted swarm attacks on the battlefield for much of the past year, according to a senior Ukrainian officer and the company that makes the software. The previously unreported attacks are the first known routine use of swarm technology in combat, analysts say, underscoring Ukraine’s position at the vanguard of drone warfare.

Swarming marries two rising forces in modern warfare: AI and drones. Companies and militaries around the world are racing to develop software that uses AI to link and manage groups of unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, leaving them to communicate and coordinate with each other after launch.

Ukraine’s military has used technology from local company Swarmer to launch drone attacks.

Justyna Mielnikiewicz for WSJ.

But the use of AI on the battlefield is also raising ethical concerns that machines could be left to decide the fate of combatants and civilians.

The drones deployed in the recent Ukrainian attack used technology developed by local company Swarmer. Its software allows groups of drones to decide which one strikes first and adapt if, for instance, one runs out of battery, said Chief Executive Serhii Kupriienko .

“You set the target and the drones do the rest,” Kupriienko said. “They work together, they adapt.”

Swarmer’s technology was first deployed by Ukrainian forces to lay mines around a year ago. It has since been used to target Russian soldiers, equipment and infrastructure, according to the Ukrainian military officer.

The officer said his drone unit had used Swarmer’s technology more than a hundred times, and that other units also have UAVs equipped with the software. He typically uses the technology with three drones, but says others have deployed it with as many as eight. Kupriienko said the software has been tested with up to 25 drones.

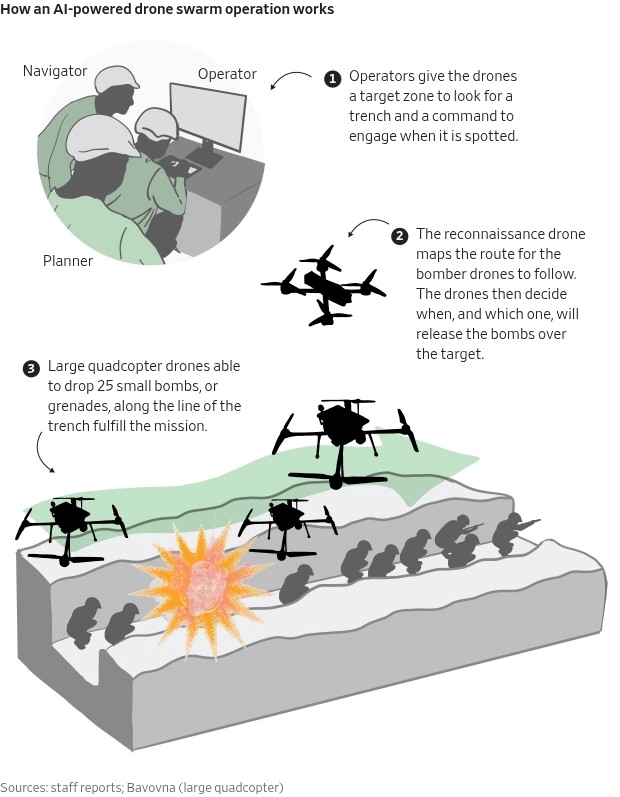

A common operation uses a reconnaissance drone and two other UAVs carrying small bombs to target a Russian trench, the officer said. An operator gives the drones a target zone to look for an enemy position and the command to engage when it is spotted. The reconnaissance drone maps the route for the bombers to follow and the drones themselves then decide when, and which one, will release the bombs over the target.

Three people are involved in these missions: a planner, a drone operator and a navigator. Without the swarm software, nine people would be required, the officer said. Using the technology saves time and frees up personnel to work on other tasks, he added.

“You don’t require a separate pilot for each drone, one pilot can work with many drones,” Kupriienko said.

That is a help for Ukraine, which is fighting an adversary in Russia with far greater manpower. Fewer operators also simplifies coordination, while having drones communicate with each other at proximity reduces the risk that the enemy can interfere with signals to the UAVs.

To be sure, the Ukrainian operations fall short of what many would consider a full swarm, said Bob Tollast , a researcher at the Royal United Services Institute, a U.K.-based think tank. That could be described as hundreds of drones moving together intelligently and autonomously reacting.

Still, “even a small level of autonomous teaming would be impressive,” Tollast said.

Swarmer said it is preparing to test a swarm of more than 100 drones.

The business, which has secured funding from U.S. investors, is one of a number of companies working on swarm technology. On a visit last year to its office, hidden in a suburban house, two young engineers worked on a ping-pong table welding circuit boards and attaching components to drones. Elsewhere, a 3-D printer noisily produced a new component.

Outside, a neighbor mowed his lawn, seemingly oblivious to what was happening next door. Drones are loaded onto vehicles in a garage away from public view.

The U.S., China, France, Russia and South Korea are among the countries pursuing swarm technology. But analysts said they weren’t aware of it being used regularly in combat until hearing of the Ukrainian operations.

The U.S. has been exploring the technology since at least 2016, when it launched more than 100 small drones from three jet fighters. “The micro-drones demonstrated advanced swarm behaviors such as collective decision-making, adaptive formation flying, and self-healing,” the Defense Department said at the time.

In 2021, officials from Israel’s military told local media that it used a swarm of small drones to locate, identify and attack militants in Gaza.

However, the Israeli military doesn’t appear to have talked about swarming since, leading some drone experts to suggest that there may be challenges with its technology. The Israeli military declined to comment.

For all drone swarms, maintaining stable and reliable communication links between the UAVs is likely to be a challenge, said Zak Kallenborn , a drone-warfare expert at King’s College London.

In Ukraine, Swarmer’s technology had teething problems. At one stage, drones were swapping too much information and overloading the network, the Ukrainian officer said.

The technology also makes drones more expensive. That is a negative for Ukraine, which burns through UAVs. The country produced over 1.5 million drones last year alone, the government said.

AI is a growing focus for militaries and is increasingly being used in combat, though mostly to analyze data or navigate.

But the rise of AI in war is raising ethical concerns about the potential for machines to make life-or-death decisions without human oversight. The United Nations has, for example, called for regulation of lethal autonomous weapons.

The U.S. and its allies require a person in the so-called kill chain under current rules of engagement.

Swarmer said a human ultimately makes the decision on whether to pull the trigger.

“Folks have been talking about the potential of drone swarms to change warfare for decades,” said Kallenborn. “But until now, they’ve been more prophecy than reality.”

Write to Alistair MacDonald at Alistair.Macdonald@wsj.com