LONDON—Fentanyl fueled the worst drug crisis the West has ever seen. Now, an even more dangerous drug is wreaking havoc faster than authorities can keep up.

The looming danger is an emerging wave of highly potent synthetic opioids called nitazenes, which often pack a far stronger punch than fentanyl. Nitazenes have already killed hundreds of people in Europe and left law enforcement and scientists scrambling to detect them in the drug supply and curb their spread.

The opioids, most of which originate in China, are so strong that even trace amounts can trigger a fatal overdose. They have been found mixed into heroin and recreational drugs, counterfeit painkillers and antianxiety medication. Their enormous risk is only dawning on authorities.

Europe, which has skirted the kind of opioid pandemic plaguing the U.S., is now on the front line as nitazenes push into big heroin and opioid markets such as Britain and the Baltic states. At least 400 people died in the U.K. from overdoses involving nitazenes over 18 months until January of this year, according to the government .

“This is probably the biggest public health crisis for people who use drugs in the U.K. since the AIDS crisis in the 1980s,” said Vicki Markiewicz, executive director for Change Grow Live, a leading treatment provider for drugs and alcohol in the U.K. Particularly worrying, she said, is that most people take nitazenes unwittingly, as contaminants in other drugs.

The U.K.’s National Crime Agency has warned that partly due to nitazenes, “there has never been a more dangerous time to take drugs.”

In the U.S., where fentanyl dominated the opioid market, nitazenes had as of last year been found in at least 4,300 drug seizures since 2019, usually in fentanyl mixtures, and have led to dozens of deaths. But reporting on the drugs is sparse and relies on self-reporting. Many overdose toxicology tests don’t include nitazenes. The Drug Enforcement Administration has warned that Mexican cartels could use their existing relations with China-based suppliers to obtain nitazenes and funnel them into America.

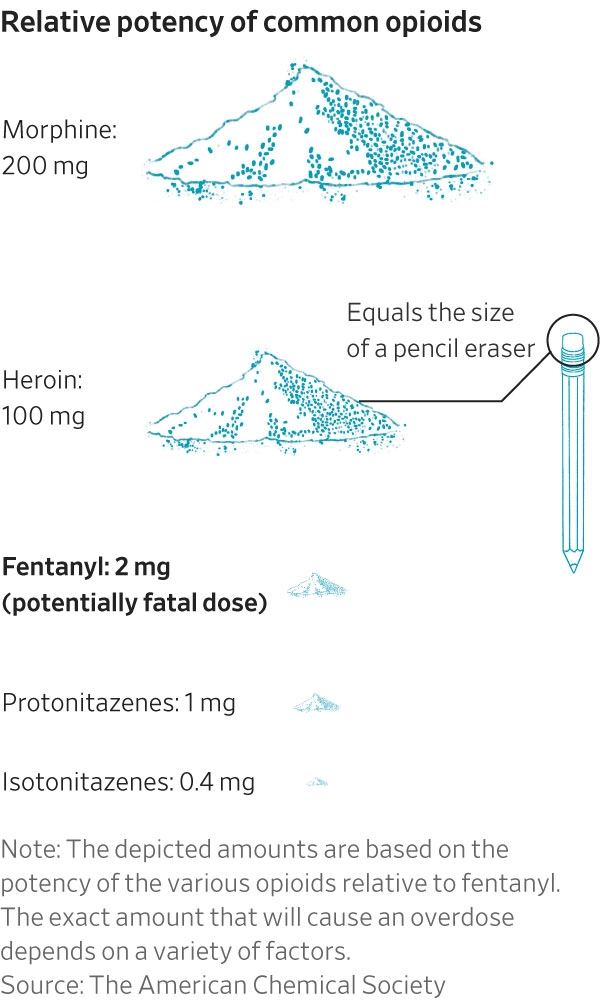

The most common street nitazenes are roughly 50 to 250 times as potent as heroin, or up to five times the strength of fentanyl. They are likely much more prevalent than official statistics suggest, due to limited testing. Authorities say official death tolls are almost certainly undercounts.

On an early summer morning in 2023, police arrived at Anne Jacques’s door in north Wales. Her 23-year-old son had died in his sleep in his student apartment in London, they told her.

Her son, Alex Harpum, was a rising opera singer and healthy. Police found Xanax tablets in his room, and evidence on his phone that he had bought pills illegally, which Jacques said he occasionally did to sleep while on medication for his attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Yet, the coroner established the cause of death as unexplained cardiac arrest, known as sudden adult death syndrome. Jacques, not satisfied with the explanation, researched drug contaminants and requested the coroner test for nitazenes. Seven months after her son’s death, police confirmed that his tablets had been contaminated with the potent opioid.

“I basically had to investigate my own son’s death,” Jacques said. “You feel like your child has been murdered.”

Harpum wasn’t alone. While most known overdoses affect heroin users, nitazenes have also been found in party drugs like cocaine, ketamine and ecstasy, in illegal nasal sprays and vapes, and detected in benzodiazepines like Xanax and Valium. In May, two young Londoners died after taking what authorities believe was oxycodone laced with nitazenes upon returning home from a nightclub.

Dealers aren’t trying to kill customers, but the globalized drug trade leads gangs to traffic a wider variety of increasingly potent substances, partly because smuggling gets easier as the volumes involved shrink.

U.K. National Crime Agency Deputy Director Charles Yates said dealers are driven mainly by greed. “They buy potent nitazenes cheaply and mix them with bulking agents such as caffeine and paracetamol to strengthen the product being sold and make significant profits,” he said.

Nitazenes are also ravaging West Africa as a prevalent ingredient in kush, a synthetic drug that has killed thousands of people and led Sierra Leone and Liberia to declare national emergencies.

“It’s an international concern. They have been detected on every continent,” said Adam Holland, an expert on synthetic opioids at the University of Bristol. “You can produce them with different chemicals that are relatively easy to get a hold of, and you can do it in an underground laboratory. And because they’re so potent, you need less for the same size of market so they’re easier to smuggle.”

Chinese suppliers sell nitazenes openly on online marketplaces sometimes using photos of young women as their profile picture. They list phone numbers, social-media handles and business addresses linked to China or Hong Kong. The drugs are sometimes labeled as research chemicals but also often explicitly as nitazenes.

The Wall Street Journal found nearly 100 profiles on the Pakistan-based web marketplace TradeKey selling different types of nitazenes, including etonitazenes, estimated to have 15 times the potency of fentanyl. Four suppliers told a Journal reporter they could send any quantity to Europe, including the U.K., and promised they could evade customs.

A spokesperson for TradeKey said the company has a “zero-tolerance policy toward the listing or sale of any controlled substances, including synthetic opioids such as nitazenes.” It said it had added various types of nitazenes to its banned products registry and blocked hundreds of accounts seen to violate its compliance rules. On “rare occasions,” a prohibited product may pass initial approvals and get listed, but the company worked to routinely clean the site, it said.

“We take this issue very seriously and are fully committed to ensuring our platform is not misused in any way. We also cooperate with regulatory and law enforcement bodies as needed,” the spokesperson said.

Nitazenes were never approved for medical use in Europe. Developed in the 1950s, they were found in trials to cause fatal breathing problems. They were detected sporadically over the years: in a lab in Germany in 1987; in 1998 in Moscow, where they were linked to a dozen deaths; and in 2003 in Utah, where a chemist manufactured them apparently for personal use.

Nitazenes appeared in drug seizures in Europe and the U.S. beginning in 2019, and began spreading quickly in Europe in 2023, their high potency leaving a trail of fatal overdoses even among seasoned drug users. In Scotland, whose population of 5.5 million has the highest overdose death rate per capita in Europe, nitazenes have been involved in 150 to 200 drug-related deaths in the past two years alone, said Austin Smith, head of policy with the Scottish Drug Forum charity.

“Imagine mixing salt in sand on a beach, it’s impossible to do that evenly,” he said.

Europe’s medical practices have protected it from fentanyl, which first took off in the U.S. in the 1990s due to private prescriptions and aggressive marketing. However, Europe is vulnerable to opioids in ways that echo the American experience. The second big boost in fentanyl usage in the U.S. came in the 2010s, when drug cartels began adulterating the heroin supply with fentanyl.

So far, nitazenes appear to be supplied by individual brokers and sellers, but Europe is rife with international drug gangs that could turn to nitazenes.

“Synthetic opioids in the U.S. have not been driven by demand, they have been driven wholesale by supply,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, senior fellow and expert on the global opioid trade with the Brookings Institution, a think tank. “If large criminal groups such as Albanian mafia groups, Turkish criminal groups or Italian or Mexican groups get into supplying nitazenes to Europe on a large scale, we can anticipate a massive public healthcare catastrophe.”

They may be prompted to do so. Since the Afghan Taliban most recently banned in 2022 the cultivation of poppies , which supplied about 90% of the world’s heroin, experts have warned that a heroin shortage could lead gangs to cut the drug with other, more dangerous substances. Nitazenes are at the top of the list.

“If the heroin supply is interrupted, that will have a knock-on effect on drug use within Europe, and on things users can turn to in the absence of heroin, such as synthetic opioids and synthetic crystal meth,” said Andrew Cunningham, expert on drug markets with the European Union Drugs Agency.

The tiny nation of Estonia has firsthand experience of what that is like. When the Taliban first banned poppy cultivation in 2000, fentanyl flooded the Estonian drug market as a replacement for heroin. Drug-related deaths grew fourfold in two years, and put the Baltic country in a fentanyl grip that it was unable to shake. For a decade, from 2007 to 2017, Estonia had the highest per capita overdose death rate in Europe. And Estonia is already feeling the influx of nitazenes, which since 2023 have been involved in nearly half of all drug-induced deaths in the tiny Baltic nation.

When a batch of drugs contaminated with nitazenes hits the streets, it often results in a cluster of overdoses. Late last year, about 80 people overdosed and needed medical treatment in Dublin over a weekend. In March of this year, at least 31 users overdosed over a few days in Camden, north London.

One of them, Tina Harris, 41, who has been using heroin since her early teens, said she bought a £5 bag of what she thought was fentanyl from a drug dealer in Camden.

“He told me, ‘be careful because it’s strong.’ I thought he was just chatting sh—,” she said. After smoking the drug, she passed out, and survived only because a friend administered shots of naloxone, an antidote that users carry for emergencies, until the ambulance arrived.

Harris woke up in the hospital, rattling from withdrawal. Since then, she has twice saved the life of friends who mistakenly took nitazenes, by providing naloxone and CPR. She has become increasingly worried about the drug supply in London, but said her addiction is impossible to kick.

“It’s a devil’s trap,” she said.