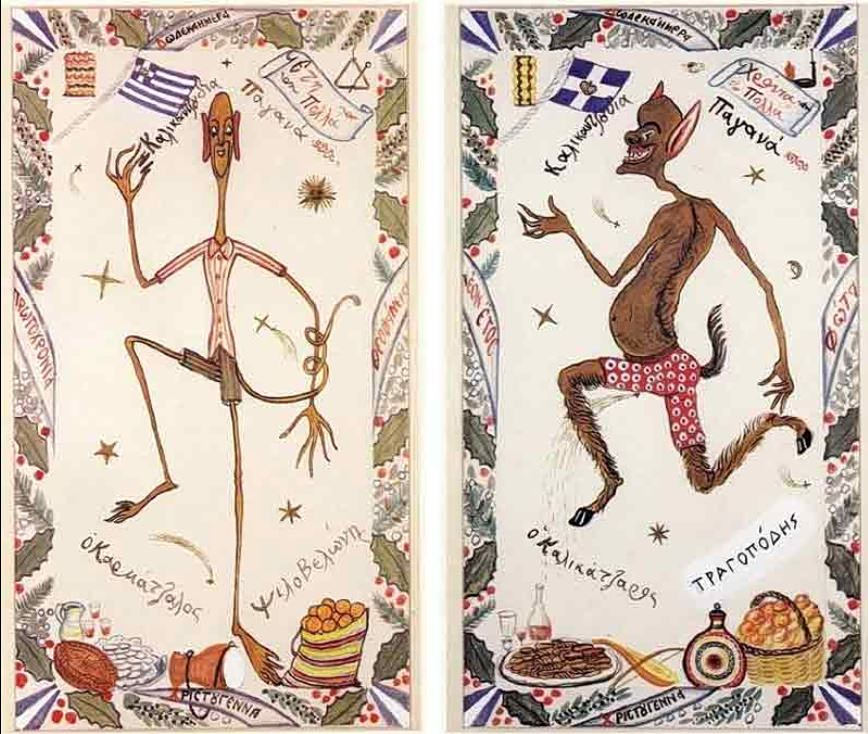

They come in every shape imaginable—tall or short, thin or stout, hairy or bald, lame or whole, sometimes goat-legged, sometimes almost human. But one thing is certain: they are cunning, foolish, mischievous, and relentlessly destructive.

Across Greece, they are known by dozens of names: Kallikantzaroi, Lykokatzaraioi, Skalikantzeria, Karkantzalia, Paganá, Kolovelonides, Karkantzelia, and many more—each name tied to a specific region and local imagination.

No matter what they are called or how they appear, according to Greek folk tradition they all arrive on the same night every year: Christmas Eve.

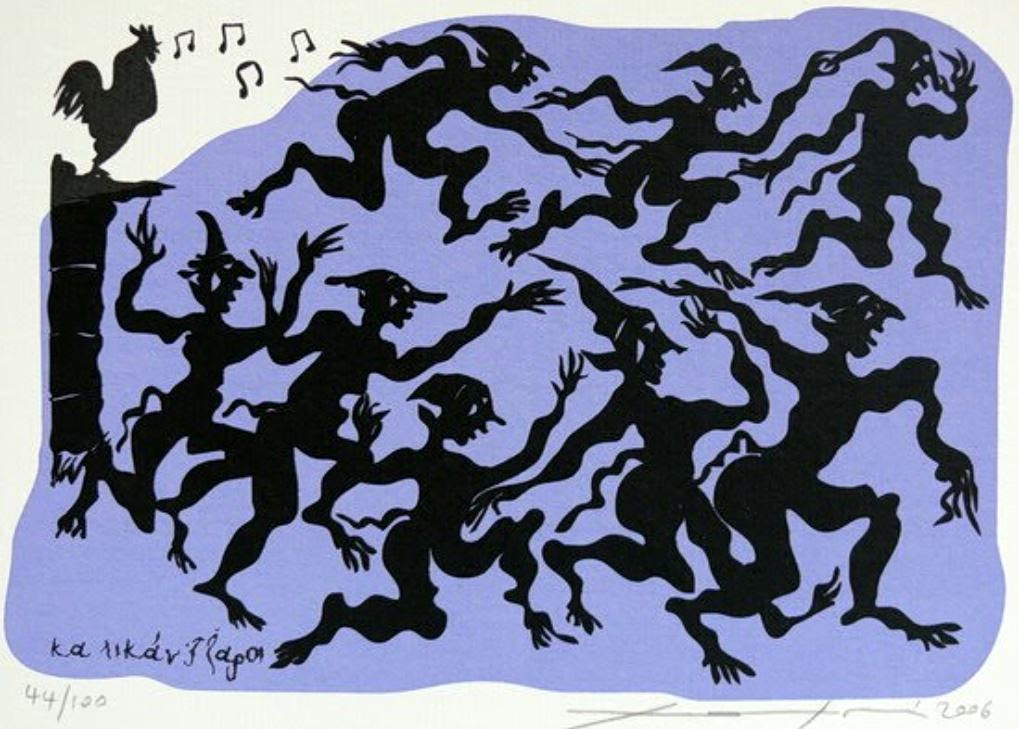

For twelve nights—from Christmas until Epiphany (January 6)—they rise from the underworld and turn the human world upside down.

Creatures of the Twelve Days of Christmas

The Kallikantzaroi are mythical beings deeply rooted in Greek folklore and linked to the Dodekaímero, the sacred twelve-day period that begins on Christmas Eve and ends with the Blessing of the Waters on Epiphany.

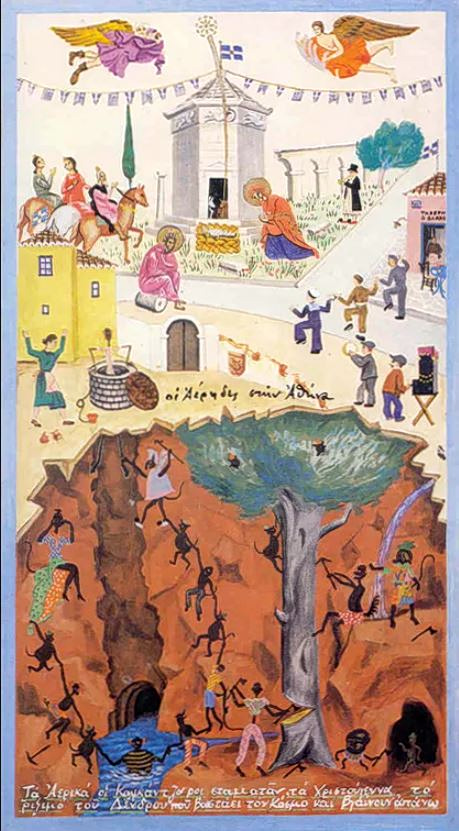

According to tradition, they spend the rest of the year underground, tirelessly sawing away at the World Tree—the pillar that holds the earth upright. Their goal is to bring the world crashing down.

Just as they are about to succeed, however, they are distracted. On Christmas Eve, the smells of festive food rising from human homes lure them to the surface. They abandon their work and emerge into the upper world to feast, mock, and cause havoc.

When Epiphany arrives and holy water is blessed, they flee in terror back underground—only to find the World Tree fully restored, forcing them to begin their futile labour once again.

Night Creatures and Household Terrors

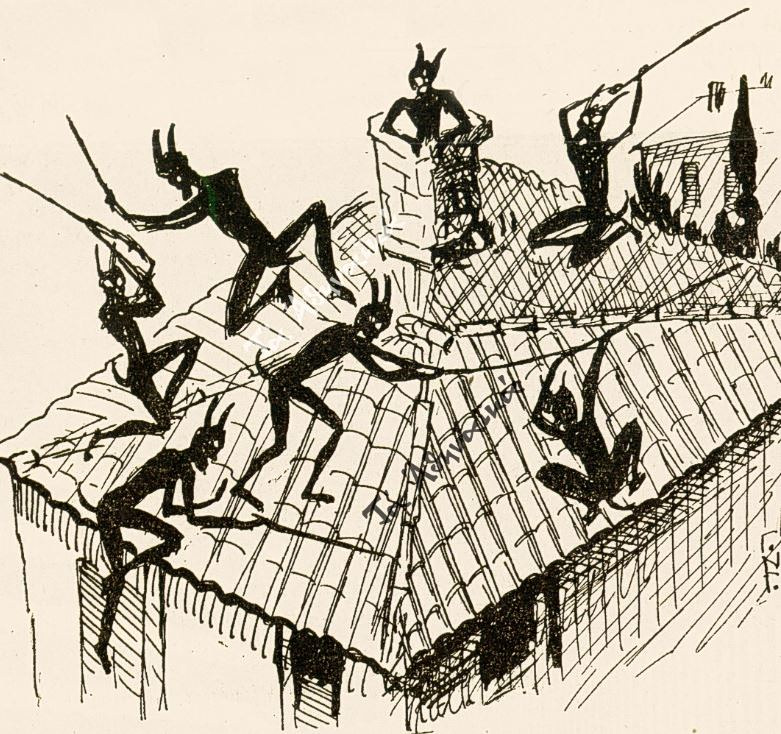

The Kallikantzaroi roam only at night. By day, they hide in dark, abandoned places. They enter homes through chimneys and cracks, spoil food, contaminate grain, extinguish fires, and delight in destruction.

To protect themselves, people traditionally:

- Keep the fireplace burning throughout the twelve nights

- Hang garlic or place a cross near the hearth

- Burn incense or scatter salt

- Avoid leaving water uncovered, fearing the goblins will defile it

Fire is their greatest fear. Ash, however, becomes their target—many traditions insist they urinate in it, rendering it impure.

Who Becomes a Kallikantzaros?

A widespread belief holds that children born between Christmas and St Basil’s Day (January 1) are at risk of becoming Kallikantzaroi if not properly baptised.

In some regions, extreme rituals were described: newborns were briefly held near fire so their nails would burn—because, according to folklore, a Kallikantzaros without claws cannot exist.

Mandrakoukos: The Leader of the Goblins

At the head of the Kallikantzaroi stands Mandrakoukos, also known as Koutzos or Cholos (“the Lame One”).

Described as short, thick-set, goat-legged, bald, grotesque, and monstrously endowed, Mandrakoukos is said to be:

- The last member of a demonic council

- The first and supreme leader of the Kallikantzaroi

During the twelve days, he lurks at crossroads and alleys, targeting unsuspecting women. Only those who know how to invoke holy words can escape him unharmed.

Regional Legends Across Greece

Arcadia (Vourvoura)

Known as Lykokatzaraioi, they nearly cut the World Tree each year—only to find it miraculously restored after Epiphany.

Chios

Here, Kallikantzaroi are savage but foolish. They terrorise passers-by, asking riddles like “Tow or lead?”—a wrong answer could mean death. Yet women mock them openly, calling them “ash-feet” and “filthy ones.”

Arachova

Called Skalikantzeria, they are comically deformed and endlessly quarrelsome—incapable of finishing any task, which limits the harm they can cause.

Portaria (Thessaly)

The Karkantzelia appear as dancers, priests, animals, or women, breathing fire and forcing humans to dance with them. Speaking during the dance risks losing one’s soul.

Argos

These goblins steal children, lure people to water to drown them, and feast on festive sweets—though always wary of being struck with a spoon.

Zakynthos

A sieve placed by the chimney confuses them—they obsessively count its holes until dawn forces them to flee.

Athens

Known as Kolovelonides, they are violent night attackers, repelled only by crosses drawn on doors.

Symi

Children born on Christmas Eve become Kaídes, who wander the streets at night unknowingly, harmless but possessed by an unseen force.

Constantinople

Hairy female creatures called Verveloudes descend chimneys with the goblins, used to frighten misbehaving children into sleep.

Why Fire Saves and Ash Is Cursed

Across all versions, one truth remains constant:

The Kallikantzaroi fear fire.

They descend chimneys to extinguish it, urinate on ashes, and flee when flames roar or incense crackles. For this reason, ashes were never cleaned during the twelve days—only covered and discarded after Epiphany.

When holy water finally appears, the goblins cry out in panic:

“Let’s go! The mad priest is coming with holy water!”

And just like that, they vanish.

A Folklore That Still Burns Bright

The stories of the Kallikantzaroi were meticulously recorded in 1904 by folklorist Nikolaos G. Politis, the founding father of Greek folklore studies. His work preserved regional voices, dialects, fears, and humour—offering a rare glimpse into a world where myth explained winter darkness and ritual protected everyday life.

Grotesque, comic, frightening, and absurd, the Kallikantzaroi remain one of the most vivid symbols of Greek Christmas tradition—a reminder that between light and darkness, belief once mattered as much as warmth itself.

And perhaps, somewhere deep underground, they are still sawing away.