The evolution of China’s higher education system reflects a constant negotiation between external influence and domestic priorities. Historically, China has selectively borrowed from foreign models—first from the West in the late 19th century, then from the Soviet Union in the early years of the People’s Republic.

Reforms have played a decisive role in shaping this trajectory. Following the founding of the PRC in 1949, radical reforms imposed a Soviet-style system that emphasised specialised training, strong state control, and the alignment of universities with economic planning. After 1978, a new wave of reforms introduced under the open-door policy drew heavily on Western ideas, including liberal arts education, marketisation, managerial efficiency, and internationalisation. These two reform phases—Sovietisation and post-1978 globalisation—restructured Chinese higher education and set the foundation for its modern success.

In the 21st century, reforms have continued under Xi Jinping, with the “Double First-Class” initiative aiming to elevate China’s top universities and disciplines to world-class levels, with 80 Chinese universities in the top 500 according to the 2025 Global Web Rankings for Universities. At the same time, the government has tightened ideological supervision, mandating greater emphasis on political education, loyalty to the Party, and the integration of national priorities into research agendas. This dual strategy seeks to balance global competitiveness with political control, ensuring that higher education serves both developmental and ideological purposes.

This vision reflects a distinctly Platonic understanding of education as a tool of statecraft. For Plato, the task of education was to form philosopher-kings capable of ruling wisely and preserving the moral order of the polis. Chinese universities function in a similar way: they are tasked not only with advancing research and innovation but also with producing graduates aligned with the political and cultural values of the state. This Platonic orientation finds a natural parallel in the Confucian tradition, where education for centuries meant the cultivation of virtuous officials through the imperial examinations, binding intellectual achievement to civic responsibility. Both traditions converge in treating education as inherently political and moral, rather than purely intellectual.

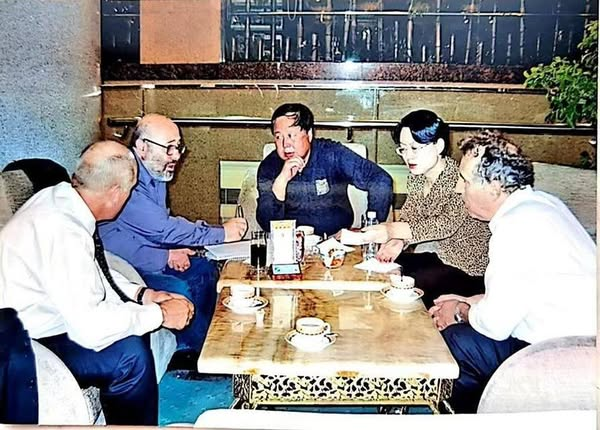

Photo taken some time in 1998 in Shenyang, a meeting with colleagues Robert Sims, Roman Tomasic (RIP) , professor Zang Shuliang, and Ms Cao, a meeting to build trust foremost that paved the way for one of the first joint institutions the “Asia-Australia Business College (AABC) a Sino-foreign educational joint institution established by Liaoning University and Victoria University in September 1999 with the license NO.MOE21AU02DNR20000014O awarded by the National Ministry of Education.”

The Onset of Transnational Education Reforms in 2025

Since 1978, transnational education (TNE) has been one of the most visible expressions of China’s participation in global higher education. With 15 international branch campuses, 333 joint colleges, and 2,427 joint education programs, around 800,000 Chinese students are currently enrolled in TNE initiatives. I was privileged to have been associated on the ground with developing and managing TNE ventures in China, with Charles and other colleagues. Notably, joint international business programs between Victoria University and Liaoning University Australian-Asian Business College (Shenyang-China), and the Central University of Finance and Economics School of International Business (Beijing-China) , thus enhancing educational cooperation between Australia and China.

Yet the scale is now set to expand dramatically: the Ministry of Education has signalled its intention to increase TNE enrolments to 8 million students, positioning TNE as a strategic mechanism for both educational reform and economic transformation. The forthcoming reforms, previewed at a series of policy briefings from May to September, aim to lower entry barriers, clarify third-party involvement, and standardise applications, while increasing transparency for institutions and foreign partners. However, these liberalising measures are tightly circumscribed by principles of quality, sovereignty, and cultural alignment. The state’s expectations remain clear: universities must reinforce Party-building, embed ideological education, and ensure that foreign curricula and expertise are genuinely imported in line with the “Four One-Thirds” rule.

In effect, China is not passively globalising its higher education system but actively shaping the terms of engagement. TNE is welcomed as long as it contributes to national capacity-building, talent cultivation, and economic upgrading, while safeguarding ideological control and cultural sovereignty. The result is a carefully managed form of globalisation—opening the door wider, but only on China’s own terms.

The Bertrand Russel and Nikos Kazantzakis Prophecy about China in the Modern Era

Bertrand Russell’s “wisdom” regarding China centers on his book, The Problem of China, where he advised China to develop an orderly government, industrialization under national control, and universal, scientific education, rather than simply adopting Western models. He believed Chinese civilization had a unique “pacific temper” and would offer the world a new model for life, but only if it modernized effectively to resist Western exploitation and fostered its own culture and intellectual traditions. Nikos Kazantzakis, whose heart was also won by China, had the same way of thinking. When he fell ill during his last visit to China, he longed to spend the rest of his life there. Later, he was honored by the Communist Party as a great writer and lover of peace. It is no coincidence that during his November 2019 visit to Greece, in his official speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping referred to Nikos Kazantzakis as a giant of modern Greek literature.

Thus, through the passage of time China’s higher education system has developed as a hybrid one: shaped by globalisation and Western models, yet deeply rooted in its Platonic and Confucian conception of education as the cultivation of leaders and citizens for the service of the state. In this way, Chinese higher education today stands at the crossroads of Plato, Confucius, and globalisation, embodying a unique synthesis of ancient philosophy, cultural heritage, and modern ambition.

* Steve Bakalis is a Visiting Professor at Central University of Finance and Economics. Charles Sun is the Founder and Managing Director of China Education International.