If someone wanted to hurt Europe tomorrow morning, they would not start with tanks at our borders or trolls on our screens. They would start by reaching up, quietly, into the thin ring of metal and silicon that surrounds the planet, the satellites that make European life possible, mostly unnoticed. German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has called this our Achilles’ heel in space. Strip away the drama, and he is describing daily life. The phone that guides you, the card you tap, the hospital that schedules your visit, the flight that lands on time, the encrypted line between minister and general: all depend on signals that originate far beyond the atmosphere. We only see this plumbing of our civilization when it breaks.

In Ukraine, we saw what happens when someone turns the taps. On the first day of the invasion, a cyberattack on a commercial satellite network disrupted communications for Ukrainian forces and took thousands of wind turbines in Germany offline. Russian jamming and spoofing of GPS have repeatedly interfered with navigation in the Baltic and the High North, forcing aircraft and ships to reroute. No missiles, no Hollywood explosions, just code and radio waves aimed at an invisible infrastructure that we assumed was safely out of reach.

The uncomfortable truth is that Europe has been treating this infrastructure as if it were a free good: always available, always benign, someone else’s problem. It is not. Space is a strategic arena in which major powers are making long-term choices. The question is whether Europe is one of those powers or just one of the customers.

The United States answered that question by creating a Space Force, folding space into every serious military plan and harnessing the private sector. Thousands of American commercial satellites now provide the backbone for communications, navigation and imagery for the alliance. When a private constellation suddenly became indispensable to Ukraine’s defense, it became clear that European security could hinge on a contract in California and the mood of a single owner.

China has chosen the opposite of delegation. Its space program is tightly bound to the state and the armed forces. Beijing is building its own global navigation, communications and observation systems and quietly developing the tools to interfere with those of others. In this vision, space is leverage: you depend on me; I depend on no one. Russia, unable to match either, specializes in disruption, jamming, hacking, testing anti-satellite weapons, and shadowing other countries’ spacecraft in orbit.

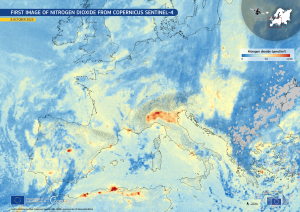

Europe is something else: a space power by necessity, still catching up in strategy. It runs Galileo, a precise navigation system, and Copernicus, an Earth-observation program indispensable for climate, agriculture and crisis response. European governments have now asked their common space agency to deliver for security and defense, backing a new resilience-from-space “system of systems” for secure surveillance, communications, navigation and crisis imagery and a three-year space budget of €22.1bn, a third higher than before, though a sliver is earmarked for defense. On paper, this looks impressive.

But strategy is not a list of program; it is a choice. Europe still hesitates. Launcher delays have forced us to rely on foreign rockets, even as we pour money into new European designs without a coherent plan. Governments and armies use services from non-European companies for crucial communications. A new space security center on the EU’s eastern flank will help, but responsibility for space infrastructure is split between EU institutions, NATO and national authorities, with too many ministries, no single owner and little appetite to pay for redundancy before a crisis. We are rich, capable and exposed.

Put simply, Europe has three paths. We can keep muddling through, assuming that American and commercial systems will always be there when we need them. We can try to do everything ourselves, replicating the full American or Chinese toolbox at the European level, an ambition that would take decades and matching budgets. Or we can do something more subtle and more appropriate to what the EU actually is: we can build allied autonomy.

Allied autonomy means recognizing that the transatlantic alliance remains vital, while also deciding that some functions are too critical to outsource. Europe should be able to guarantee basic capabilities: secure communications for governments and the armed forces, precise timing and navigation, crisis-time observation, a surveillance network, and assured access to orbit on European launchers. These are the equivalent of ports and railways a century ago.

This does not require Europe to mirror every American system or to deploy exotic weapons in space. It does require treating space as core infrastructure in budgets and industrial policy, not as a side-project of telecoms and research. It means backing the new surveillance and communication constellations from design to launch, hardening satellites and ground stations as if interference were a matter of when, not if, and building enough redundancy into the system that no single failure (technical, political or commercial) can switch off a continent.

There is also a diplomatic side to this. Europe is at its best when it turns power into rules. In orbit, as on Earth, we need norms: against debris-creating tests, against reckless manoeuvres and for basic transparency. A Europe that invests in launchers, constellations and space security centers has more standing to set those norms with allies and to link them to access to its market and security partnerships. But rules without capabilities are sermons. If Europe wants a say in how space is used and contested, it has to bring both to the table.

Europeans will never see the satellites that tie their lives together; they notice them only when something goes wrong. Political leaders do not have that excuse. They have been warned in Berlin that Europe’s Achilles’ heel is in orbit. The choice now is whether to keep walking on it, or to turn it into the backbone of a Europe that is secure, prosperous and, yes, still allied, but no longer strategically sleepwalking above the clouds.

This opinion piece was selected to be published within the framework of To BHMA International Edition’s NextGen Corner, a platform for upcoming voices to share their views on the defining issues of our time.