The arrival of artificial intelligence (AI) has presented challenges, including placing higher education at the center of a debate reshaping teaching, learning, assessment, and academic integrity. Regulators such as the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) in Australia have made it clear that universities must adapt responsibly, building frameworks that ensure AI supports—not substitutes—human judgment, ethical reasoning, and genuine learning.

As someone associated with the higher education sector, I have witnessed the excitement, anxiety, and confusion unfolding across the university sector. Students wonder what counts as “their work” in an AI-assisted world. Academics fear that critical thinking may be overshadowed by algorithmic shortcuts. University leaders grapple with the need to innovate while safeguarding educational values. In many ways, the dilemmas we face echo the great technological shifts of the past.

Society Has Been Threatened — and Has Adapted — to Technological Change

Every major technological shift documented in history has arrived with both hope and fear. Yet history shows that while disruption is inevitable, societies adapt—and often emerge wiser and stronger.

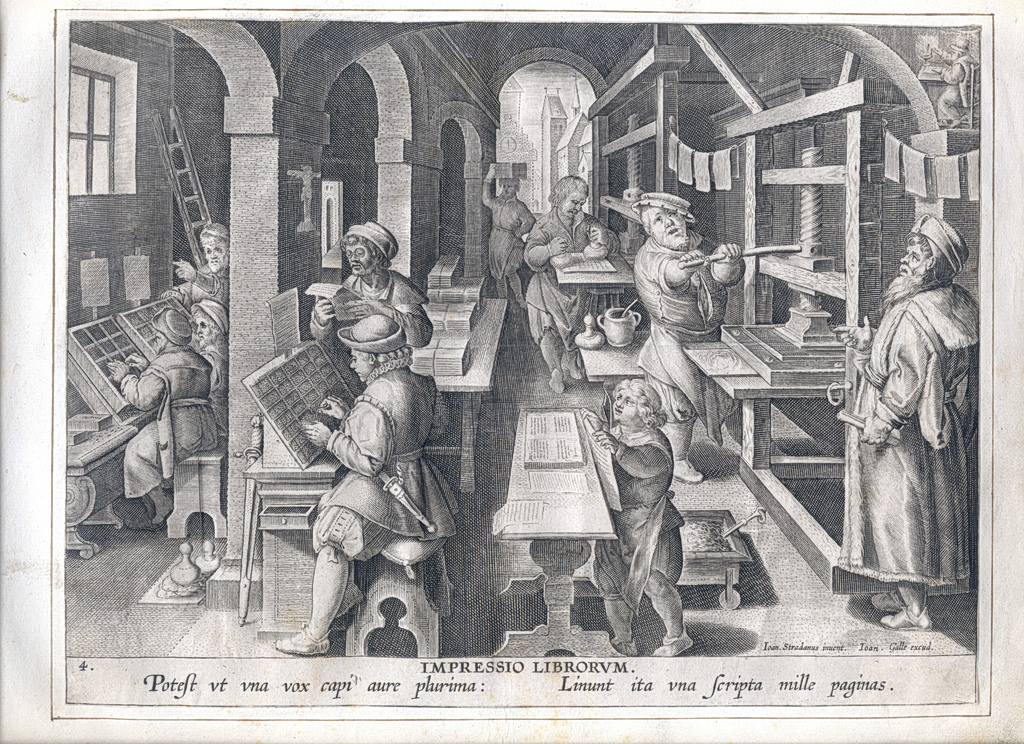

The Printing Press (15th century)

Gutenberg’s invention was feared for undermining tradition and spreading dangerous ideas. Instead, it democratized knowledge, expanded literacy, and birthed the scientific revolution.

The invention of printing, anonymous, design by Stradanus, collection Plantin–Moretus Museum in Antwerp, Belgium. /Stradanus, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Industrial Revolution (18th–19th centuries)

Automation displaced craftsmen, triggered unrest, and destabilized economies. Ultimately, new industries emerged, productivity rose, and labor protections evolved. During this period, the economist Frédéric Bastiat mocked fears of technological progress with his satirical “Petition of the Candlemakers”, exposing the absurdity of trying to halt innovation. His message is timeless: progress cannot be stopped, but it must be guided.

Electrification and Mass Production (20th century)

Critics warned that assembly lines would deskill workers and dehumanize labor. Yet electrification raised living standards, created new professions, and transformed society.

Computers and the Internet (late 20th century)

Predictions of mass job loss and social fragmentation did not materialize. Digitalisation introduced new challenges, but also new industries, and modes of learning.

Lesson Across Eras

Technological disruption initially threatens existing systems and identities, but societies adapt by reinventing institutions, re-skilling workers, and redefining roles. Today’s AI revolution echoes the same tension. As The Guardian notes, mere “tool competence” is no longer enough; the differentiator is how humans direct, constrain, and ethically steer these tools.

AI, Misinformation, and Expertise in a Global Context

Against this background Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa has repeatedly warned that the greatest threat democracies face today is not a single leader or ideology, but the technology infrastructure that amplifies falsehood, outrage, and authoritarian tactics. “Without facts, there is no truth; without truth, there is no trust; without trust, there is no shared reality,” she has argued — and without shared reality, democratic societies fracture. Platforms optimized for engagement reward emotional manipulation over accuracy, creating information ecosystems where lies flourish faster than evidence.

This challenge is now recognized globally. In Australia, the government has just introduced a restriction banning social-media access for under-16s — a response to concerns that young people are particularly vulnerable to misinformation, algorithmic manipulation, and AI-generated content. The law signals growing recognition that digital environments require stronger protections for younger users and clearer standards for trustworthy public discourse.

In China, policymakers have taken a very different but equally consequential approach. A national credentialing system requires influencers discussing expert-level topics to display verified professional or academic qualifications. Unverified content risks suppression or removal. Officials argue this raises the baseline quality of online discourse and helps combat AI-driven misinformation, while critics warn it may limit diversity of viewpoints and suppress dissent.

Global Dilemma

Free-speech environments struggle with misinformation, emotional manipulation, and declining trust.

Centralized systems can raise standards but risk narrowing pluralism and suppressing heterodox ideas.

Youth protection measures, such as Australia’s, highlight recognition that AI-generated content introduces new cognitive, social, and civic risks.

Across these contexts, one insight recurs: societies must rethink how expertise, authority, and credibility are recognized in a digital world where AI can generate persuasive falsehoods at scale. The challenge is not simply stopping misinformation — it is designing systems where trustworthy knowledge can survive and thrive without suffocating debate, creativity, or dissent.

AI in Higher Education

Back to the university challenges of our times!

As Thomas Sowell observed: “In a democracy, we have always had to worry about the ignorance of the uneducated. Today we have to worry about the ignorance of people with college degrees.” Sowell warns that credentials alone do not guarantee understanding and in an AI-driven world, confidently misinformed individuals — armed with degrees, influence, or platform — can spread misinformation as easily as anyone else. Education without critical thinking is insufficient; judgment, humility, and evidence-based reasoning remain essential.

Within universities, these concerns are daily realities. Students now face the challenge of distinguishing between assistance and substitution. AI can accelerate learning, but overreliance can hollow it out. As educators, we must design assessments that value originality, curiosity, and critical inquiry — skills AI cannot automate.

In faculty meetings, research panels, and curriculum committees, the debate centers on one question: How do we preserve the integrity of human learning in an AI-saturated world? The answer lies not in banning AI, nor in blindly embracing it, but in guiding students to use it responsibly, reflectively, and creatively. Education has always been more than the transmission of information; it is the formation of judgment, character, and intellectual independence.

Conclusion: The Light We Choose to Cast

Across history, societies confronted new technologies with fear, resistance, and adaptation. Each time, the outcome depended not on the machines themselves, but on the wisdom of those who used them.

AI presents the same challenge. Universities, policymakers, educators, and students now stand at a turning point. Tools are becoming powerful; algorithms are becoming autonomous. But meaning, ethics, judgment, and purpose remain human responsibilities.

The question is not whether AI will transform the world — it already has. The real question is whether we — teachers, students, leaders, citizens — will cultivate the wisdom needed to guide it. As history and philosophy remind us, information without judgment becomes noise, confusion, and even danger. The future will be defined not by the brilliance of machines, but by the depth of our humanity.

*Dr Steve Bakalis is an economist with interests in political economy, social justice, and public administration, having collaborated with La Trobe University, the University of Melbourne, Victoria University, and universities in the Asia-Pacific region and the Arabian Gulf.