Greece’s tax system over the past decade illustrates in stark terms the limits of apparent fiscal success. Surpluses and compliance gains suggest effective governance on paper, yet the underlying design—heavy reliance on indirect levies such as VAT, excise duties, and social contributions—continues to distort behaviour and discourage participation in the formal economy. Like a firm that sets prices too high for its customers, the state raises revenue while shrinking its economic base. Every euro collected through taxation is ultimately a euro withdrawn from citizens’ capacity to spend, save, or invest.

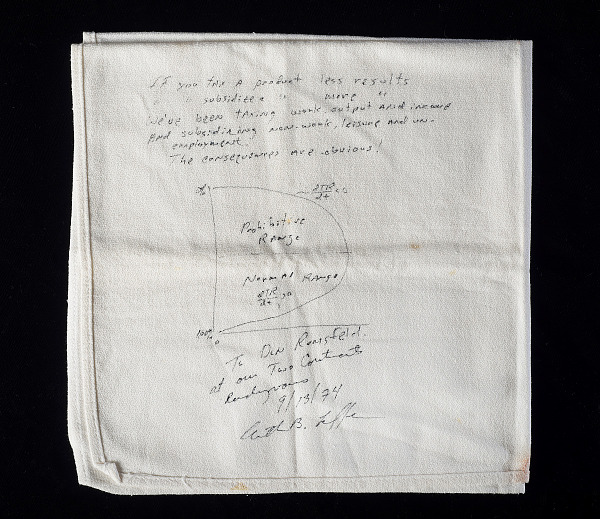

Such mechanics make Greece a textbook case of a country operating on the right-hand side of the Laffer Curve, where high rates suppress the very activity they aim to fund. The Laffer Curve, famously sketched on a napkin by Arthur Laffer in 1970, shows that between no yield at 0% tax and no yield at 100% tax, there exists a rate that maximizes revenue. Today, it is part of mainstream economics curricula and widely discussed as a diagnostic tool, illustrating the trade-off between tax rates and economic activity (Mankiw, Principles of Economics, 10th edition, 2024).

Economists across the spectrum accept the Laffer Curve as a conceptual framework: it does not prescribe universal tax cuts but highlights the risks of excessive rates in narrow, consumption-heavy systems like Greece’s. It functions much like a price set by a firm: low prices yield weak revenue, moderate prices maximise revenue, and excessive prices reduce demand. Governments face the same constraint. Beyond certain thresholds, higher rates can reduce revenue—a concept largely uncontroversial in theory.

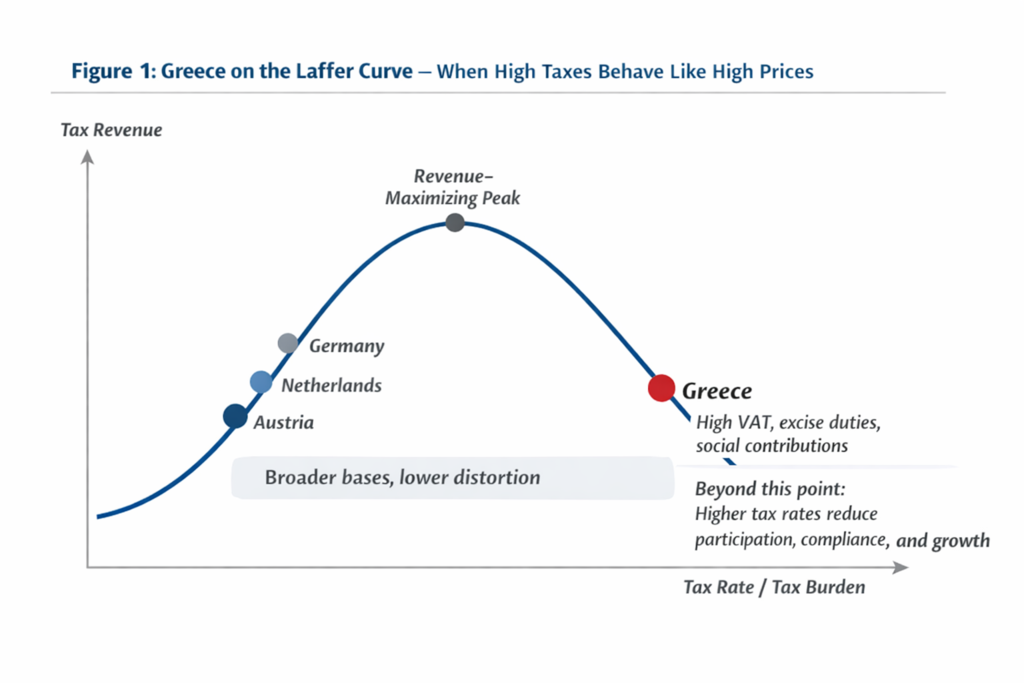

Greece on the Laffer Curve

Figure 1: Greece on the Laffer Curve — Taxation and Economic Participation

The horizontal axis represents overall tax rates; the vertical axis represents revenue collected. The red dot marks Greece’s current position beyond the revenue-maximising peak, while several Northern and Central European economies appear closer to the peak or left-hand side, supporting both compliance and growth.

It also needs to be stated that maximizing revenue at the Laffer Curve peak is not necessarily the government’s objective. The goal is to secure sufficient funding while maintaining participation, supporting growth, and preserving social stability. High rates beyond the peak may boost short-term receipts but risk undermining the very base—labour, consumption, and investment—from which revenue is drawn.

Enforcement Gains and Structural Limits

Recent enforcement improvements illustrate both progress and limits. Between 2017 and 2023, Greece reduced its VAT gap from 29% to 11.4% through digital invoicing and real-time reporting (VatUpdate – VAT Gap Data). This mirrors a firm improving billing systems: essential, yet insufficient. Perfect collection cannot overcome structural rate pressure.

In 2025, Greece recorded a primary budget surplus of roughly €12.65 billion through November, well above initial targets (Reuters – Greek Budget Data). Strong tax receipts and restrained expenditure contributed, but the surplus also reflected early inflows from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). From a Laffer Curve perspective, this distinction matters: a surplus achieved via enforcement and front-loaded EU funds does not prove that tax rates are economically optimal. With the RRF ending in 2026, growth momentum may slow, exposing structural fragility (To Vima – Greece in 2026).

This highlights a European paradox: the EU enforces fiscal discipline through common rules yet tolerates wide divergence in tax design. Countries with similar obligations achieve very different growth outcomes, exposing a gap between formal fiscal consistency and economic cohesion.

Fiscal Literacy and Governance

Headline surpluses matter less than composition. Systems heavily reliant on indirect taxation risk weakening the economic base if inflows fade or compliance gains plateau. Yet surpluses also offer opportunity: rebalancing the tax mix, easing pressure on labour and consumption, and implementing reforms that broaden the base rather than raise participation costs. Done well, this shifts Greece closer to the Laffer Curve’s peak—maximising sustainable revenue without suppressing activity.

Greece’s experience reveals a governance challenge: high rates persist because they are administratively reliable and politically legible, not economically efficient. Power exercised without economic literacy mistakes enforcement for reform, surplus for sustainability, and control for competence. There is a fundamental truth: there is no “public money.” All funds are taxpayers’ money—raised through direct taxation, borrowing, or inflation—and must be managed responsibly.

Conclusion: Fiscal Literacy Before Fiscal Power

Greece’s fiscal challenge is no longer one of discipline but of design. Surpluses and compliance gains create the appearance of success, yet the tax structure continues to discourage participation, growth, and investment. Like a firm priced out of its market, the state risks shrinking its economic base while competitors attract capital and opportunity.

The lesson of the Laffer Curve—and basic pricing theory—is simple: revenue is maximised through balance, not pressure. High “prices” reduce demand. Narrow bases magnify distortion. Enforcement cannot substitute for sound design. Sustainable public finance, like any business model, depends on aligning rates with behaviour, authority with knowledge, and revenue with long-term trust. As Daron Acemoglu observes, countries falter not merely from lack of discipline, but from extractive institutions that inhibit opportunity (Acemoglu & Robinson, Why Nations Fail, 2012).