From the Truman Doctrine to John F. Kennedy, and from Barack Obama’s rolled-up sleeves to Zohran Mamdani, Greece has historically drifted along the political currents blowing from the United States.

In the streets and in the digital trenches. From door to door and from reel to reel. Zohran Mamdani, the newly elected mayor of New York City, blended the real and the virtual, defeated Andrew Cuomo’s extremely costly campaign, and sparked global attention.

In Greece, however, we typically experience only the echo. We try to decode the original message—arriving from afar—and then apply it to our own political and social reality, whether by following American “trends” or by adopting strategies crafted for U.S. politics that end up awkwardly patching over long-standing Greek dysfunctions.

Greece is not America, yet it repeatedly tries to align with American ideas or to follow the U.S. playbook—the Truman Doctrine being a defining example.

To understand just how easily American political winds reach Greece and reshape public discourse—therefore shaping political behavior—we return to the protagonist of our small story: Zohran Mamdani.

View this post on Instagram

After Mamdani’s Victory

In the days following his win, many rushed—on social media, of course—to discuss his communication strategy: how he managed to “speak” the language of ordinary people he met on the streets while also speaking the language of young voters on digital platforms. According to these commentators, this dual fluency is precisely what Greece’s Left lacks.

If, in time, Greek political strategists begin producing Mamdani-style content—or something close to it—it will hardly be surprising. As we have already said, political winds blow from across the Atlantic, and we simply raise our sails, albeit with delay. Where those winds ultimately lead us is another story—one whose roots extend deep into history.

According to Jenny Lialouti, Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Political and Social History of Europe at the University of Athens, the relationship between the U.S. and Greece can be seen through three distinct lenses of political influence:

- Geopolitics and bilateral relations in the postwar era.

- Ideological currents and processes circulating between the two countries.

- Political communication, where the U.S. has long set global standards.

The Truman Doctrine and Anti-Communism

Concerning the first dimension: beginning with the Truman Doctrine and American economic aid to Greece, an asymmetrical relationship formed from 1947 onward. At times, this relationship even involved direct U.S. intervention in Greek domestic politics.

“Such cases,” Lialouti notes, “usually came through the American Embassy. One example is the intervention against the minority government of Sophocles Venizelos in 1950—a government favored by the Palace—which paved the way for Nikolaos Plastiras to become prime minister. Other examples include U.S. support for Alexandros Papagos entering politics and backing the adoption of a majoritarian electoral system for the 1952 elections.”

The second dimension concerns ideological influence. A major example was anti-communism during the Greek Civil War and the post-civil-war era, shaped by the American effort to position itself as leader of the “Free World” against Soviet totalitarianism. Greek anti-communism also adopted this rhetoric of anti-totalitarianism and Western freedom.

A key challenge—for both the American and the Greek versions—was balancing the ideal of freedom with the ideal of security, the latter often prevailing.

But anti-communism was not the only ideological transfer. “Important,” Lialouti adds, “was the influence of the liberal-modernizing model that developed in the U.S. and inspired parts of Greece’s academic and political elite in the late 1950s and early 1960s.”

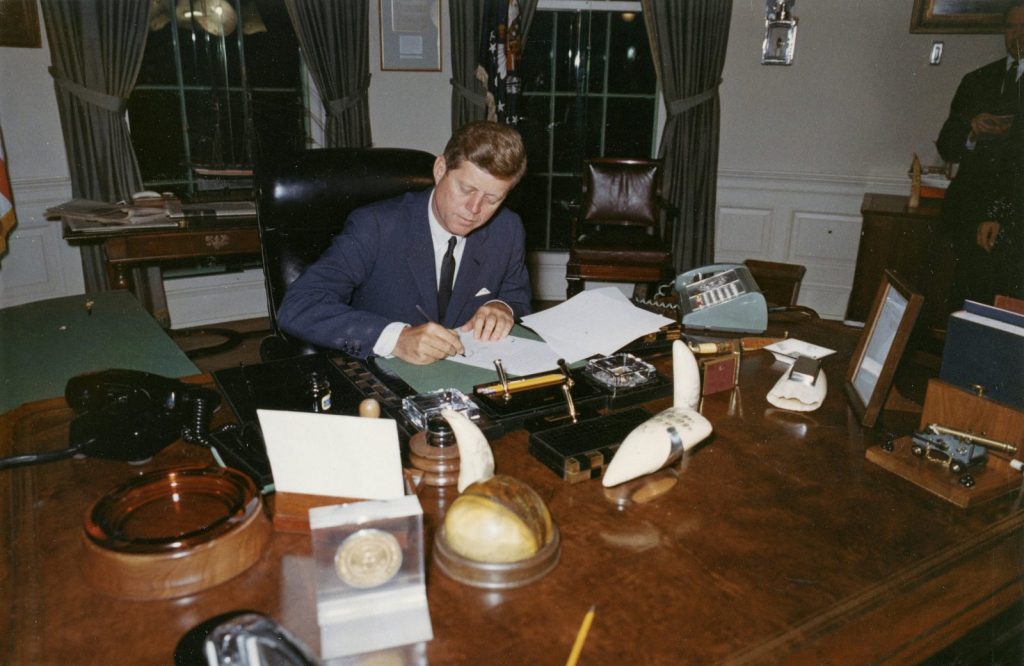

JFK, Vietnam, and Anti-Americanism

The presidency of John F. Kennedy (1961–1963) marked the peak of this influence. Lialouti notes that the arrival of Andreas Papandreou in Greece in 1961—after a distinguished academic career in the U.S.—can be viewed through this lens. He first took on a technocratic role as head of the Centre of Planning and Economic Research (KEPE), then entered politics, becoming a minister in the Center Union government and a member of parliament in 1964.

Beyond Papandreou’s personal presence, American influence was visible in the processes that led to the formation of the Center Union in 1961. In the wake of the 1958 elections—in which the left-wing party EDA became the main opposition—the U.S. encouraged and supported the creation of a centrist formation capable of challenging Konstantinos Karamanlis’ ruling party.

Meanwhile, in the 1960s, political and social protest—especially among the Left and left-wing youth—had both national and international roots. The denunciation of the Vietnam War and American imperialism became central themes. Their rhetoric and methods drew heavily from the protest movements shaking the U.S. at the same time.

The so-called “other America”—the America of radicalism and dissent—became a powerful ideological reference point for young Greeks. Throughout the postwar era, political (and sometimes cultural) anti-Americanism coexisted paradoxically with a growing Americanization of social and cultural practices.

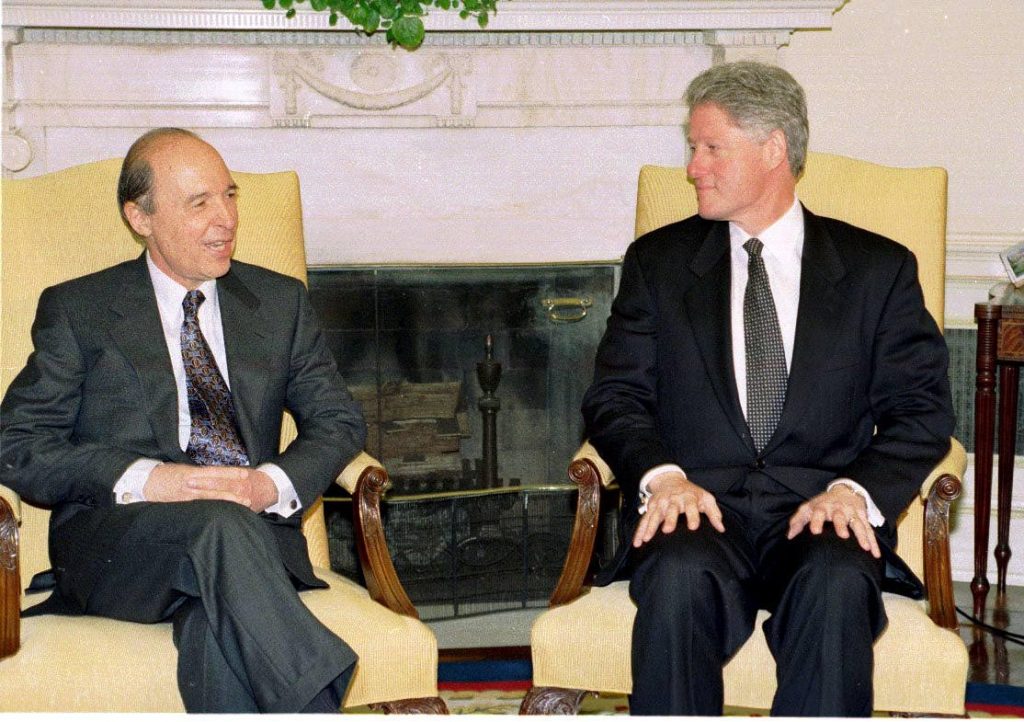

From Bill Clinton to Kostas Simitis

The third dimension of influence is political communication. Throughout the 20th century and into the present, the United States has set the global pace, pioneering concepts and techniques long before they reached Greece.

This is why analysts often speak of the “Americanization of political communication”—meaning a shift toward candidate-centered politics and an expanded role for professional consultants.

In the early years after Greece’s return to democracy (the Metapolitefsi), the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) was accused by its opponents of being the first Greek party to use “Madison Avenue methods,” referring to the use of American political consultants. Given the strong anti-American sentiment of the era—and PASOK’s own anti-American rhetoric—these accusations were politically convenient.

In the 1990s, a new model emerged: the Third Way of Bill Clinton’s New Democrats and Tony Blair’s New Labour. The political trajectory of Kostas Simitis and the modernizing wing of PASOK was often interpreted through this lens. Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign popularized the concept of “triangulation,” introduced by strategist Dick Morris.

Triangulation involves blending left- and right-leaning positions to transcend traditional ideological divides. From the 1990s onward, the logic of triangulation influenced Greek politics as well—and resurfaced during discussions about New Democracy’s 2023 election campaign.

Obama’s Rolled-Up Sleeves

In the late 2000s, Barack Obama’s election redefined the global conversation around political communication. “His campaign,” Lialouti says, “was a milestone: it pioneered the internet as a fundamental tool for outreach and relationship-building with voters, and it mobilized demographic groups typically underrepresented in U.S. elections.”

The white shirt with rolled-up sleeves—projecting a dynamic yet less elitist style—and the variations of the slogan “Yes, we can” became widely imitated, including in Greece. What resonated less, however, was the genuinely bottom-up, participatory nature of the Obama movement, which balanced professional strategy with grassroots enthusiasm.

From Mamdani’s Win to Trump’s Shadow

Recently, Mamdani’s victory in New York—he is a young Muslim immigrant—sparked debate in Greece about the lessons it might offer for political communication and mobilization, particularly regarding the future of the Greek Left.

Yet, as Lialouti warns, such discussions must consider the vast differences between national and local elections—not to mention elections in a multicultural megacity. The community-based character of U.S. political mobilization is also essential to understanding how such victories are built.

Moreover, American influence today is far from one-sided. The potential inspiration drawn from Mamdani’s style is only one face of the coin. The other is the spread of Trump-era patterns—in political style and rhetoric—into Greek politics.

Recent endorsements by Greek politicians of gun ownership, for example, can be interpreted within this framework. Likewise, the escalation of political hostility, often framed as a rebellion against supposedly oppressive “political correctness,” reflects similar trends.

Elements of Trumpism are already visible in Greek political life, Lialouti concludes, and they are reshaping part of the country’s right-wing landscape.