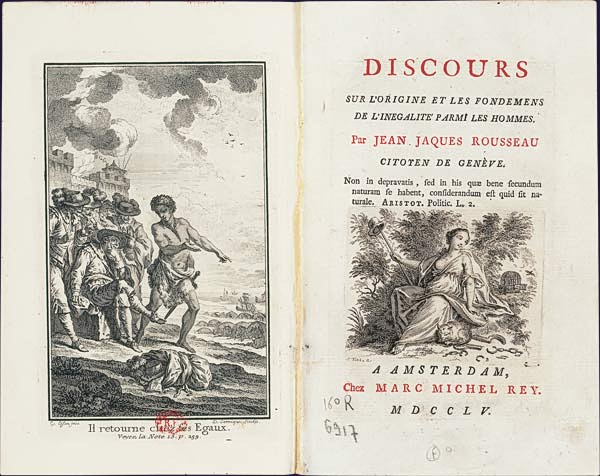

Two hundred and seventy-one years after the publication of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men, his enlightenment spirit returns to his birthplace, Geneva, on the occasion of a series of commemorative lectures on inequality organized by the Rousseau Association and the University of Geneva in collaboration with To Vima. In this conversation, moderated by Association president Martin Rueff (MR), the world-renowned Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel (MS) talks to the Greek Minister of Economy and Finance and President of the Eurogroup, Kyriakos Pierrakakis (KP). MR: “When does inequality cease to be a strictly economic issue and become a wound in the body of democracy? Can we understand inequality without asking ourselves about the common good?”.

MR: “When does inequality cease to be a strictly economic issue and become a wound in the body of democracy? Can we understand inequality without asking ourselves about the common good?”.

MS: “Two years ago, my family and I were vacationing in Florida. I remember one day I met a woman in the elevator of the building where we were staying. She asked me: “Where are you from?”. I replied: “From Boston.” “I’m from Iowa. And I’d like you to know that we can read in Iowa,” she said. When the elevator reached her floor, just before she got out, she added: “You know, we don’t like people from the coastal states very much.” The woman was almost definitely middle-class, maybe even upper-middle-class. So there was no question of her being at the receiving end of financial injustice. But tinged with bitterness as they are, her words relate to the wound you mentioned, and in particular to the demand for dignity and social recognition that underpin the polarization that plagues many societies and has paved the way for an authoritarian populist backlash against the establishment. Kyriakos, are you experiencing a rift and this sort of simmering discontent in Greece and more broadly? Do you believe recent decades have seen a failure of the mainstream parties of the center-left and center-right to address ever-deepening economic inequalities? A failure that has helped transform economic inequality into inequalities of respect, dignity, recognition and appreciation?”

Kyriakos Pierrakakis: “That’s a very good question, Michael. I will start by saying that it’s wrong to view the economy in terms of data alone, devoid of social context. Of course there are some objective variables: being able to make a living, for example, and support a household. But over and above these, there are inequalities of opportunity and parameters affecting social mobility that are crucial for the maintenance of social cohesion. Our world is evolving exponentially, and political parties everywhere in the world, not only in Europe, can’t always respond to exponential challenges. While we still interpret the world linearly in our head, it is actually becoming increasingly exponential. What’s more, political systems also tend to react in the old, linear way. I would add that our political vocabulary has changed little since the 1970s and 1980s, even though we now live in an entirely different era. In order to address emerging inequalities and the developmental challenges they pose, we must also adapt our vocabulary. And one more thing. As a student, I was influenced by Robert Putnam’s work on social capital and how we structure social relations as a function of social systems and the economic “equation” I mentioned. This emerging sense that certain groups do not “belong” in society is also a result of an erosion of trust and, in some cases, an unpicking of the social fabric. Which means we need new tools in our education, and in our social security and health systems, which will help us tackle the inequalities that are emerging faster than in the past.”

MR: “Michael, is meritocracy a promise we can keep or a tale we need to rewrite?”

MS: “Certainly, in the United States and in Europe, meritocracy is looked upon as the ideal. If the alternative to meritocracy is aristocracy or feudal privilege or the distribution of social roles and opportunities on the basis of birth or origin—if the alternative is nepotism, favoritism and corruption—, then meritocracy could serve as the definition of a just society. But suppose we could achieve perfect meritocracy, with everyone enjoying genuine equality of opportunity. Would that make for a good society? I’d argue it wouldn’t, because meritocracy has a dark side. Even a perfect meritocracy would be corrosive to the common good. Why? Because it would encourage the “successful” to believe their success is entirely their own doing, and that they deserve the prosperity the market has bestowed on them. By extension, anyone who falls behind should simply accept their fate. This somewhat brutal mindset fuels both the divide between winners and losers and the anger and resentment we see today.”

Statements by the Greek Minister of National Economy and newly elected President of the Eurogroup Kyriakos Pierrakakis in Brussels, on 11 December 2025. / Δηλώσεις του Έλληνα υπουργού Εθνικής Οικονομίας και νεοεκλεγέντα προέδρου του Eurogroup Κυριάκου Πιερρακάκη στις Βρυξέλλες, στις 11 Δεκεμβρίου 2025

KP: “It all depends on the definitions. The same term can mean different things. Context matters. If we are talking about meritocracy in a society that has set improving and upgrading its institutions as a common goal, then it is a good thing. But if we are talking about meritocracy as a destiny defined by social position and birth, then it’s negative.

My motto as Minister of Education was excellence, meritocracy (in the sense of striving to become the best version of yourself, whatever that may be, not of social status), and access to the tools required to achieve both. Is that fully feasible? No. But it is what we should aim for in the new social structures of the 21st century, and do so taking the rapid technological developments into account. The key challenge for any minister of education today, as it’s shaped by artificial intelligence and the technologies of the 4th industrial revolution, is to design a system of education for the four-year-olds starting school which looks ahead to the world those same children will be inhabiting at eighteen. What will the jobs of tomorrow be? What skills do you give them so they have a genuine opportunity to pursue their dreams? So the challenge translates into choosing the right tools and into radical new policies which seek to provide every child with opportunities, while simultaneously ensuring a level playing field. I feel we have a great deal of work ahead of us, but very little time.”

MS: “I see two problems with our current educational systems, in so far as they reflect the tyranny of meritocracy. One is justice, meaning inequalities of income and wealth that are transformed into inequalities of honor, recognition, respect and dignity. Meritocratic institutions that entrench and preserve inherited cultural advantages. But there is a second problem: the corrosive effect meritocratic competition has on the way we teach students and the way they themselves perceive the intrinsic mission of education, which is nothing less than fostering a love of teaching and learning, reading, deliberation, critiquing our ethical and civic convictions, understanding what is worth caring about and why, and which career paths are worthy of our moral and human aspirations. The endless networking, the pursuit of titles and credentials, the rivalry, the whole culture that deflects education systems from their mission.”

MR: “Kyriakos, you also served as Minister of Digital Reform. My question is whether there is such a thing as a digital public good. What should be universally accessible in a digital democracy today?”

KP: “If I may, I’ll start by linking this issue to something Michael said, because what we are defining and how is crucial once again. Is excellence a wall or a ladder? Is it an affirmation of social achievement or does it encourage social mobility? I believe it’s the latter. We must pitch our goals at what a society can achieve at every level. In Greece, a traditionally bureaucratic country, we created a platform, gov.gr, through which citizens can access thousands of services from home or work, instead of having to visit public services in person. And it has proved extremely popular. The question is do you redesign services to empower citizens. Think how important that is for people with disabilities, for workers with families who can’t spend hours wading through a Kafkaesque bureaucracy. But there is also the world which Orwell describes. So smart regulation, like the GDPR, promotes our values with regard to how technology can protect citizens. And this is where the Collingridge dilemma comes into play: regulate too early and you can damage growth, but leave it too late and you achieve very little. The challenge, especially for Europe, is how to be both an innovator and a regulator. Let me add that, at the end of the day, technology policy is not about technology itself; it’s about citizens’ needs. In this light, technology can support social mobility.”

MS: “Kyriakos, I like your emphasis on the purposes technology can serve. And I would like to add the role it can play in education. One example are the online courses we developed to give everyone free access to my classroom at Harvard. But I have a reservation: Do we really want fair access for all children to all social media platforms that monopolize their attention, keep them glued to screens, and direct their attention to trivial things or—worse— outrageous things that fuel societal anger? Over and beyond access, we need to pay attention to how these platforms are or are not cultivating citizens capable of reasoning together, formulating arguments together and consulting each other with mutual respect rather than consuming enticing ‘content’ on their screens.”

KP: “After four years as Minister of Digital Governance, I became Minister of Education and one of the first things I did, influenced by Jonathan Hyde’s book, which the Prime Minister and I read in the summer of 2024, was to ban mobile phones in Greek schools.”

MS: “How did that go?”

KP: “At first we were a bit worried about the mandatory nature of the measure, but teachers embraced it, as they believed it had value for the social capital of the classroom as well as for the educational process itself. With certain exceptions, it has worked exceptionally well.”

MS: “What about social media bans, like the one Australia recently introduced in schools?”

KP: “We are looking at what we can do about children and young people accessing social media. Here again, the data in Hyde’s book speaks for itself; we need targeted policies. Let us not forget that the devil is in the details. If regulation isn’t done right, exploitative situations arise. The way the algorithms interact with brain functions has been shown to be problematic, especially in younger children. Policy makers cannot ignore this. And another thing: when we formulate policies, we usually have an economist and a lawyer in the room. I think we also need people who understand technology. Not necessarily people who write code, but people who understand how technology works, and how it can create arenas with winners and losers if left unchecked.”

MR: “One last question to both of you. What do you consider the moral duty of political leadership to be today? Honesty, imagination, protection? In other words, what makes for good leadership when it comes to confronting inequality?”

KP: “I wouldn’t choose a single quality. Balance is certainly needed, which is markedly lacking in many parts of the world. And humility, too: knowing what you don’t know, but also knowing that you have to ask the right questions. A lack of efficiency is another thing that erodes trust in many societies. When we say we have to do something, we have to do it well and effectively. When we fail, we have to acknowledge the failure and regroup quickly. The way political competition works today has eroded confidence in politicians’ ability to effect change quickly and on a large scale. We need to be more curious, and to combine flexibility and speed in generating solutions.”

MS: “I agree that effective governance can help restore trust, but I would add that we also need to build and nurture communities, to re-weave the moral fabric that holds societies together. One of the most corrosive aspects of recent decades has been the alienating effect of inequality. Wealthy people, and those of more modest means, are increasingly living entirely separate lives. We send our children to different schools. We do not associate with people from other social and ethnic backgrounds. I think we need to build a broad, democratic equality over and beyond mobility by creating shared public meeting places within civil society, which will remind us of everything we share as citizens.”

KP: “And these spaces can’t just be digital, Michael. Digital can add to what you rightly suggest, if it’s properly designed, but it can never form its core. We need physical interaction; we need to be in touch with each other.”

MS: “I absolutely agree.”

MR: “Thank you both. I think this dialogue highlights the respect, care and humility that can characterize a conversation between a politician and a philosopher”. Michael Sandel is Professor of Political Philosophy at Harvard University. In 2025, he was awarded the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy, which is considered the equivalent of the Nobel. Kyriakos Pierrakakis is Greece’s Minister for the Economy and Finance. In 2025 he was elected president of the Eurogroup. Martin Rueff is Professor of French Literature at the University of Geneva and President of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Society. In 2025, he was awarded the Henri-Gal Grand Prize for Literature.

The conversation was organized and edited for To Vima by Angelos Alexopoulos.