It was just a few months after we’d landed in Madrid when I found myself in a pediatrician’s office, clutching a squirming, crying baby. Our daughter was about one, deep in her “I hate doctors’” phase, and my fledgling Spanish wasn’t helping. The moment she spotted that white lab coat, she transformed into a howling, flailing ball of fury and tears.

Once the doctor had kindly assured me my child would, in fact, survive this week’s virus, she suddenly launched into a passionate description of a book she had fallen in love with. Between the wails, I caught a few words. It was by a Greek writer… something about the police or maybe a detective? “Oh! Markaris!” I exclaimed as the pediatrician nodded ecstatically. And there we were: a Greek, a Spaniard, and one hysterical baby, bonding over “Inspector Haritos”.

It was the first time in all my years abroad that I had met a foreign reader of modern Greek literature “in the wild.” Homer, Plato, Sophocles, and Cavafy are the staples most non-Greek speakers know, but the modern canon rarely crosses borders. In 1957, The UNESCO Gazette published a list of the world’s most translated authors between 1948 and 1955. Lenin reigned supreme with 968 translations. Plato appeared in 32nd place with 229, followed by Homer (172) and Sophocles (110). In the list’s latest iteration, only Plato remains.

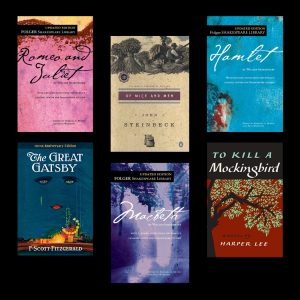

Thankfully, the roster of Greek authors translated and published abroad has grown and finally extended beyond the marble halls of antiquity. Giorgos Seferis, Odysseas Elytis, Yannis Ritsos, Nikos Kazantzakis, Emmanuel Roidis, M. Karagatsis, Ilias Venezis, Georgios Vizyenos, Alexandros Papadiamantis, Stratis Tsirkas, Penelope Delta, Dido Sotiriou, Margarita Liberaki, and Antonis Samarakis are among those who have reached international readers.

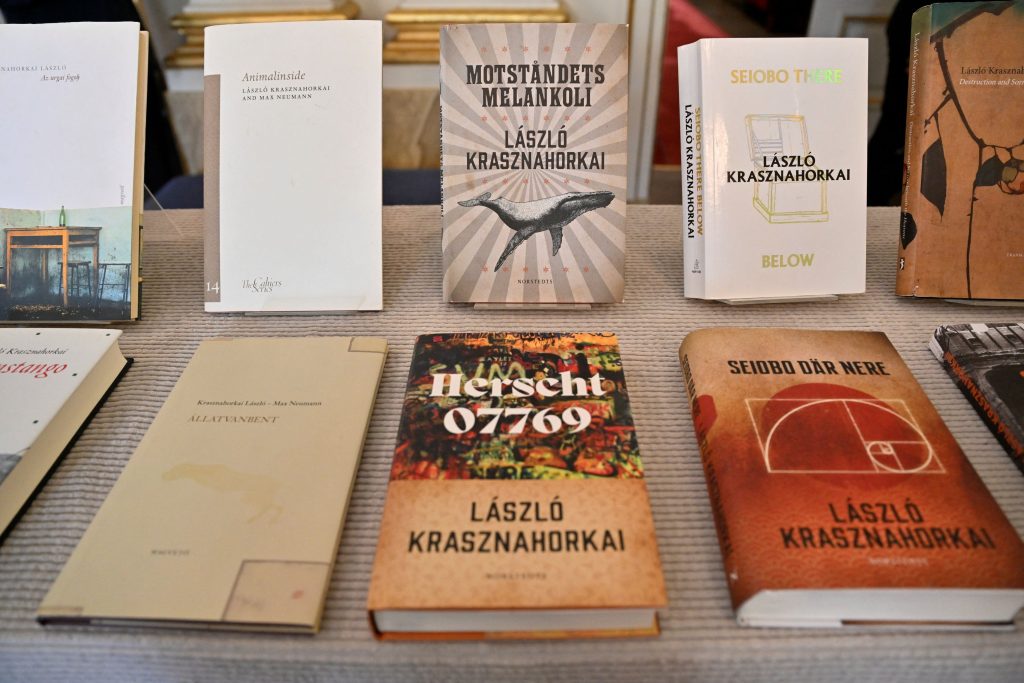

Foreign-language editions of contemporary Greek authors on display at a bookstore in Athens./ Photo by Myrto Polymili

In more recent decades, Rhea Galanaki with Eleni, or Nobody and The Life of Ismail Ferik Pasha, Apostolos Doxiadis with Uncle Petros and Goldbach’s Conjecture, Petros Markaris with his Costas Haritos detective series, and children’s favorite Eugene Trivizas with The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig have all expanded Greece’s literary footprint.

Photo by Myrto Polymili

Yet within Greek literary circles, there’s a consensus that the country’s literature still hasn’t found the international audience it deserves. The explanations vary. Some cite the language’s limited reach, a few million speakers worldwide. Others suspect that foreign publishers see Greek fiction as too bound to themes of civil war and tragedy.

Nikos Bakounakis, who has led the Hellenic Foundation for Books and Culture (HFBC) since its establishment just over a year ago, is cautiously optimistic. “Publishers in non-English-speaking countries do want to include Greek authors on their lists,” he tells To Vima International Edition. “Anglophone publishers, however, rarely translate from other languages at all. Only about 3% of literature published in English is translated. It’s a self-sustaining literary ecosystem, constantly replenished by writers from across the English-speaking world: the U.S., the U.K., Ireland, South Africa, Australia, Canada, New Zealand.”

Evangelia Avloniti, founder of the literary agency Ersilia, knows the difficulty firsthand. “It took me a couple of years to realize how hard it is for Greek authors to find a home abroad, especially in fiction.” She founded Ersilia at the onset of Greece’s financial crisis, a result of “a series of fortuitous events,” she says. From the start, she represented both Greek authors internationally and foreign publishers and literary agencies in Greece.

Her early successes included Christos Ikonomou’s Something Will Happen, You’ll See and Nikos Dimou’s On the Unhappiness of Being Greek. “Apart from being incredible books,” Avloniti recalls, “they also had special relevance for international publishers at the time, given the Greek economic crisis.” The acclaim didn’t translate into major profits. “Advances were low, and sales modest,” she says. Friends teased that her new profession looked more like “an expensive hobby.” Not anymore.

Everything changed when Stefanos Xenakis and Theodore Papakostas entered the scene. The Gift—Xenakis’s runaway bestseller, a collection of stories about compassion and empathy—became one of the “biggest non-fiction success stories in Greece in a decade.” “When Stefanos approached me to represent the book internationally, I jumped at the chance,” Avloniti says. The gamble paid off. The Gift has since sold in 31 territories, performing strongly across major markets. “We’ve had heated auctions in the U.K., the U.S., Germany, France, and Spain, which rarely happens with Greek titles,” she raves.

Somewhere along the way, Avloniti started to expand the agency. Avgi Daferera, who specializes in children’s books, joined her at Ersilia. They also started working as primary agents, representing Greek authors in Greece as well.

Ersilia Literary Agency’s children’s agent Avgi Daferera with founder Evangelia Avloniti (right) at the 2024 Frankfurt Book Fair. / Photo by Ersilia Literature Agency

Around 2020, Theodore Papakostas, better known online as Archaeostoryteller, entered the picture. His debut, How to Fit All of Ancient Greece in an Elevator, was described by the Times Literary Supplement as a light-hearted book that takes you on a whistle-stop tour of Ancient Greece. It “has sold more than 50,000 copies in Greece and has been acquired by 17 international publishers following competitive auctions among major houses. It has since become a bestseller in several countries”, Avloniti recounts.

These successes not only established Ersilia on the international map, they also made the agency financially sustainable for the first time. Avloniti credits a combination of factors: a distinctive book, strong domestic sales, and a full English translation. Both Xenakis and Papakostas benefited from their publisher, Key Books, which invested early on in complete translations, the kind of practical support that opens doors abroad, she reiterates. “It’s been easier and more profitable to sell Greek non-fiction abroad than fiction,” she reflects. “These two books have made Greek authors a little more visible.”

The Gift— Stefanos Xenakis’s runaway bestseller on compassion and empathy — and How to Fit All of Ancient Greece in an Elevator by Theodore Papakostas, better known as Archaeosto-ryteller, are two of Greece’s standout successes among international publishers./ Photo by Ersilia Literary Agency

Bakounakis, clear-eyed about the economics of translation, emphasizes the role of public funding. “For a book to reach readers abroad, authors and publishers must rely on translation grants,” he says. The GreekLit program, launched in 2021 by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, aims to provide this type of financial assistance. The initiative, which has been under the purview of HFBC since last year, subsidizes the translation of Greek works across every category of writing. So far, more than 60 translation grants have been approved into 21 languages, ranging from English, French and German to Catalan, Georgian, Arabic, Albanian, Rumanian and Turkish, permitting a small but significant constellation of Greek voices to find new readers across the globe.

During our discussion, Bakounakis points to Norway as a success story. “Through its publicly-funded foundation NORLA, the country built an entirely new literary brand: Nordic noir–and its global success owes much to translation grants, coordinated promotion, and a strong festival presence.”

Petros Markaris, Bakounakis notes, offers both a model and a path forward for Greek authors. His celebrated series featuring “Inspector Costas Haritos”, the detective with a fondness for dictionaries and Athens’s endless traffic jams, captures the shifting socio-economic rhythms of modern Greece. The books have captivated readers far beyond the country’s borders; Italy’s Rai 1 even adapted them into a television series, Kostas, which streamed in the United States this summer.

Avloniti agrees that translation grants can be transformative. “When we lament the scarcity of Greek successes abroad,” she says, “we forget that we’re not the only ones producing great fiction and non-fiction. Extraordinary titles are emerging from every corner of the world. Publishers need a reason to choose a Greek book over, say, a Romanian, Slovenian, or Catalan one.”

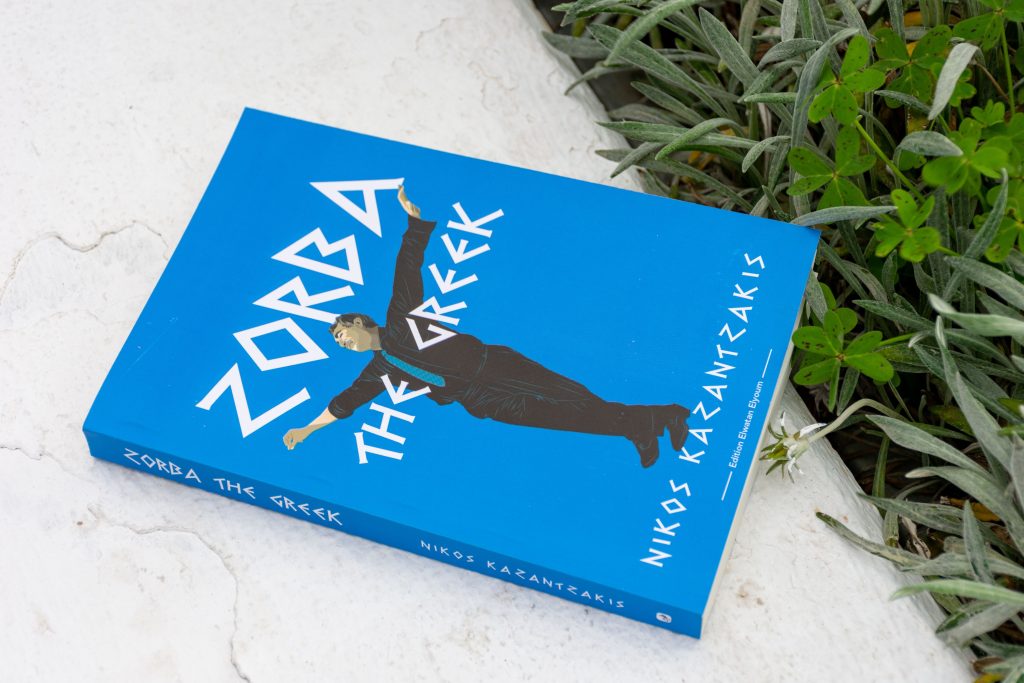

Nikos Kazantzakis’ 1946 novel Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas.

Notwithstanding financial considerations, it seems that the future of Greek authors abroad may depend less on grand institutions than on momentum—the quiet, cumulative force of a few voices breaking through, slowly but surely. As Bakounakis reiterated during our discussion, it takes only a couple of writers to open the gates for the rest, and a couple of fortuitous occasions, like Greece’s upcoming role as the guest of honor at the Turin International Book Fair in May 2026. With more and more Greek authors being translated every year, that sea change may already be under way.