Early Monday morning. The ferry departs from the picturesque harbor of Katapola on Amorgos, bound for Piraeus. Only a few passengers are on deck. Among them is 40-year-old Michalis from Naxos, visiting the Cycladic island for the first time with his girlfriend, enchanted by the “Τhe Big Blue”, made famous by Luc Besson’s 1988 film. “Did you notice that even the cats of Amorgos seem happy? Unfortunately, we’ve changed. Unplanned development and over-tourism have destroyed our islands. I hope the same doesn’t happen here,” he confides just before disembarking in Naxos.

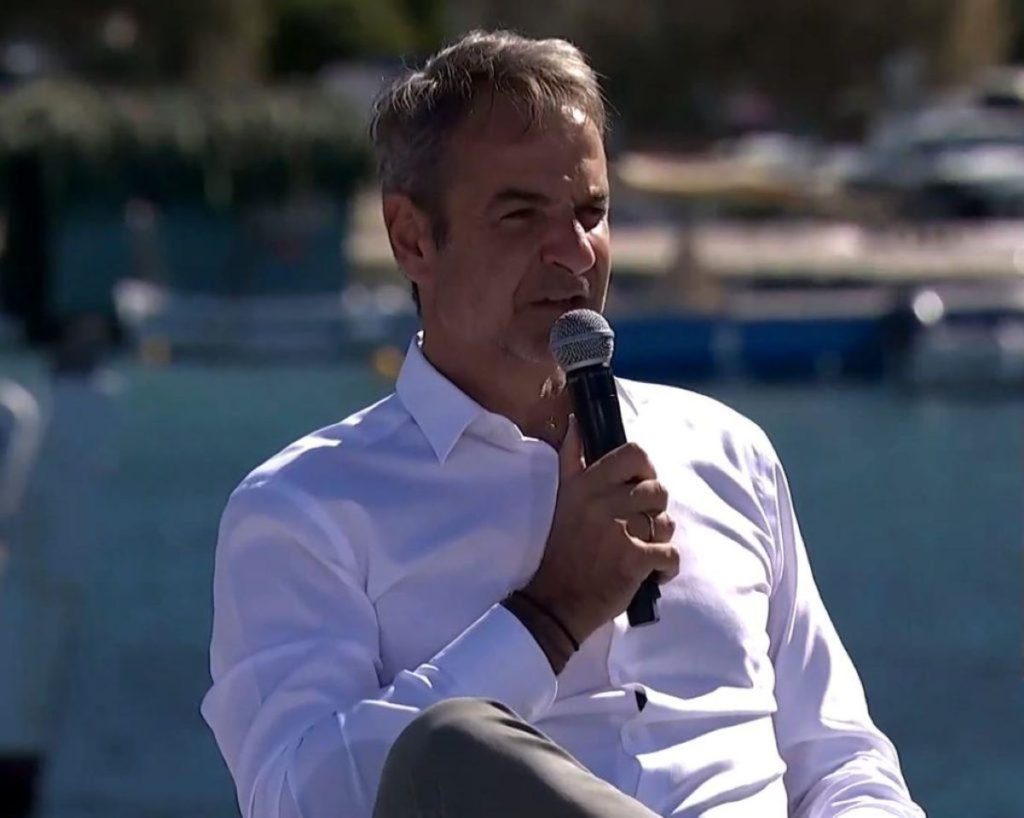

Two days earlier, Amorgos welcomed Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, accompanied by four ministers, three Cycladic MPs from New Democracy, and the EU Commissioner for Fisheries and Oceans, Costas Kadis, for the celebration of “Amorgorama”. The emblematic initiative, born in 2013 by the island’s own fishermen, aims to protect the marine environment and sustainably manage fisheries. Last August, it was codified by Presidential Decree 73/2025—the first of its kind in Greece. The decree bans commercial and recreational fishing around the island within a 1.5-nautical-mile radius during the critical spawning months of April and May and imposes a full prohibition in the Katapola area and the islets of Gramvousa and Nikouria.

A Turning Point Since the 1990s

Amorgorama has become a living laboratory of the so-called “quadruple helix” of innovation for sustainable local and regional development. It gradually grew from collaboration between the Professional Fishermen’s Association of Amorgos “Hozoviotissa”, the Cyclades Preservation Fund (CPF), the Blue Marine Foundation (BMF), the Agricultural University of Athens, and the local government authorities, the South Aegean Region, and the relevant ministries (Development, Environment and Energy, Shipping and Island Policy).

“By the mid-1990s, Greek fisheries production had already reached a turning point. After 2010, the situation worsened dramatically, with fishermen using ever more equipment to achieve the same results. By 2015, the fishermen of Amorgos realized they couldn’t continue like this,” says Vangelis Paravas, scientific advisor to the CPF. Similarly, Michalis Krosman, president of the Professional Fishing Association of Amorgos, recalls that most people assumed the sea’s resources were endless—but stocks were declining each year, incomes were shrinking, and fuel, nets, and boat maintenance costs were skyrocketing.

Michalis Krosman came to Amorgos from Germany four decades ago as a ‘foreigner’. Today, as president of the Amorgos Professional Fishing Association, he has played a decisive role in shaping Amorgorama into a grassroots initiative. Credit: ‘Revive our Ocean’/ Brendan Hubbard

In this pressing context, the need for a new, sustainable approach to fisheries management was not an environmental luxury but a matter of survival. At the center of the effort was voluntary self-restraint: abstaining from fishing in April and May, the heart of the reproductive season, and cleaning the island’s remote northern coasts instead of using nets. Images of plastic bags, bottles, and fishing lines piling up on the boats became part of a new, humble ritual.

A Culture of Consensus and Open Assemblies

Michalis Krosman’s focus and persistence united the fishermen. Arriving from Germany four decades ago as an outsider, he quickly found a community and purpose. As president of “Hozoviotissa”, he established a culture of consensus and open assemblies, where practical management proposals were written collectively at the table. This grassroots approach allowed Amorgorama to grow organically: professionals who wanted to protect both the sea and their livelihoods began by coordinating among themselves.

“When the CPF partnership began in 2019, the fishermen already had a clear will and voice, operated by consensus, and were active in international conferences and meetings. They had even submitted their first proposals to the Ministry of Development as early as 2015,” Paravas notes. What was missing was rigorous scientific documentation. The Agricultural University of Athens stepped in to produce data and systematic monitoring. In 2022, a memorandum of cooperation was signed among all stakeholders in Amorgos in September of that year.

Under the guidance of Assistant Professor of Fisheries Biology Stefanos Kalogiros, experimental fishing using specialized equipment, biological and environmental assessments of the three zones, and socioeconomic evaluations of displaced fishing efforts were conducted. In November 2023, the fishermen themselves, including the owner of the only trawler, unanimously chose the most ambitious plan: three fully protected zones and a two-month suspension of fishing around the island. This plan became the backbone of the Presidential Decree, effective from November 18.

From Vision to Reality

After nearly a decade of emails, technical opinions, and consultations from 2015 to the 2022 Memorandum of Cooperation, the combined effort of fishermen, scientists, environmental organizations, and the state bore institutional fruit. The journey was not easy. Persistence, skillful navigation of bureaucratic obstacles, and a steady belief that a small island could show the way to a new human-sea relationship were essential. The celebration culminated last Sunday in Aegiali, the island’s second port, where the Prime Minister spoke with Michalis Krosman and Yannis Psakis, secretary of the Fishing Association, in a lively discussion moderated by Angela Lazou-Dean, Projects Manager for Greece at the Blue Marine Foundation.

The Four Critical Axes

Amorgorama has passed the legislative threshold; now it will be judged in practice. The first test concerns enforcement of the fishing restrictions. Exposed coasts and the island’s back sides face strong northerly winds, capable of challenging patrol vessels. Without suitable Coast Guard assets, the ban could be undermined, sending a mixed message to other Cycladic fishing communities. The project team prioritizes strengthening surveillance; the Ministry of Shipping has pledged to upgrade Coast Guard capabilities, and a vessel from the European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA) will be present in November.

The second axis is social justice. The April–May moratorium is environmentally necessary, but it cannot succeed if small-scale coastal fishermen are left to “live on air.” Targeted financial support and temporary compensation for lost income, based on real production data, are essential. The Agricultural University study has already calculated economic needs per vessel, providing a framework for fair compensation. Short-term gaps are covered by environmental partners; in the medium term, the state must integrate the necessary tools to ensure costs are not unfairly shifted to the most vulnerable.

The third axis is scientific monitoring. The decree sets a five-year horizon for evaluation and adjustments. Measurable data on stock recovery, age and size distribution of fish, habitat conditions, and displacement of fishing effort are critical to maintaining social legitimacy and legal resilience. Kalogiros notes that the Agricultural University of Athens has committed, together with the General Directorate of Fisheries, to monitor the decree’s multifaceted impacts.

The fourth axis focuses on funding. Monitoring, enforcement, and implementation must have a stable financial channel. The European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund’s operational program opens the door to long-term support, from scientific research contracts to surveillance equipment and participatory management initiatives.

Visibility and Transparency Are Key

Beyond these, Paravas emphasizes that successful promotion and dissemination of the model will be measured by two indicators: strict field implementation, “so the message is clear that the no-fishing zones are truly closed,” and transparent communication of results—annual reports on stocks, violations, coastal cleanups, and socioeconomic impacts. Only then will Amorgorama convince other fishing communities that self-restraint works. During the official celebration in Aegiali, Psakis summed up the initiative in one sentence: “No fisherman imagines the sea empty.”

Shortly after the officials left Aegiali, the Amorgorama team returned, satisfied, to Katapola for aerial drone mapping of the Nikouria no-fishing zone. “Personally, my interest in marine biology started with The Big Blue. That’s the truth, and somehow life brought me back here, to Amorgos,” says Kalogiros, gazing at the view. That evening, at Katapola port, the CPF organized a public screening of the documentary Ocean with David Attenborough for locals and visitors in the beautiful Botanical Park.

When the lights came on, Kristin Rehberger, co-producer and founder of the “Revive Our Ocean” initiative, addressing the global 30X30 goal, took the microphone: “There’s an old saying that it’s better to light a candle than curse the darkness. Amorgorama has lit such a candle.”