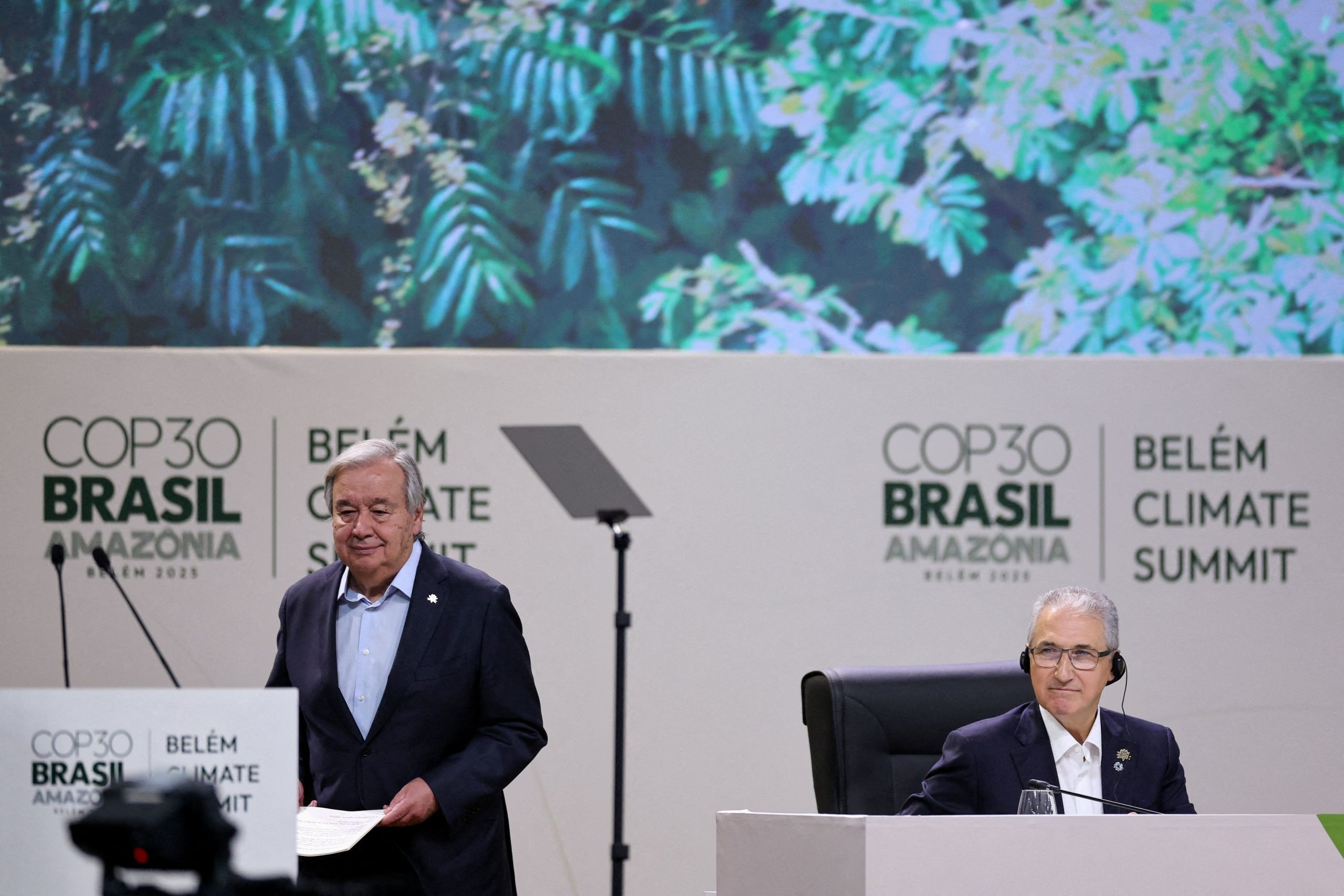

David Wallace-Wells, journalist at The New York Times and author of the influential work The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming (Metaichmio, 2019), speaks to To Vima about the COP30 Summit.

Six years after writing your warning book, are we better or worse off?

“The risks have increased. There are specific reasons to believe that the planet’s distant future may not be as bleak as it seemed likely in 2019. But in terms of public awareness and public policy, in recent years we have moved in the wrong direction. We’re seeing fewer climate protests, fewer discussions among leaders, less commitment to action. At summits such as COP, the UN General Assembly, and the World Economic Forum in Davos, climate has slipped down the scale of priorities. This by itself is not the end of the game for the climate, because decarbonization is still happening at a rapid pace. Still, there is more complacency and denial.”

What is the significance of choosing Belém as the host city for COP30?

“The Amazon has already shifted from being a carbon sink—helping to combat warming—to being a carbon source, due to logging and exploitation. This is worrying, because the Amazon does enormous work in maintaining the planet’s health. When I saw President Lula in New York last September, he said that having the world’s leaders confronted with the rainforest itself would make them understand the urgency of the crisis. Hosting the conference in a place on the front line of the climate battle is certainly important.

Beyond the Amazon, Brazil itself matters. We’re living in a geopolitical moment in which the rules of the planet are no longer set exclusively by the United States. We’re not even in a bipolar era of U.S.–China competition anymore. There is a lot of new activity and opportunity coming from developing nations in the Global South, as they seek to establish geopolitical and energy independence and climate resilience.

Thanks to falling costs of clean energy, the world’s poorer countries are now shedding carbon emissions on their own, asserting a kind of independence from global leaders. This indirectly condemns the climate policy of the last decade, during which the world’s rich nations failed to meet their decarbonization commitments. But it’s also a sign of relative hope that the world is moving in the right direction even without the support of the Global North. Many countries in the Global South are in fact moving faster.

It remains impossible to meet the goals we set in Paris a decade ago, yet geopolitical developments are creating new dynamics. I think we’ve lost something very important as we shift to a new framework where each country is expected to take on decarbonization and resilience on its own. That is a dramatic setback, but there is encouraging activity among developing countries, many of which are following decarbonization pathways faster than previously expected.”

How do you assess President Donald Trump’s stance toward COP30?

“He essentially ignores it. And when he does pay attention to it, he undermines it, through the actions of certain diplomats. One could say that Trump is following—less delicately—a policy that his predecessors also pursued in a more concealed way. On the other hand, rhetoric matters, and President Trump presents an ugly face of the United States.

The U.S. is today the world’s largest exporter of oil and natural gas. At a time when artificial intelligence requires massive cheap energy, we are doubling down on dirty, expensive energy sources and canceling domestic projects that could provide much cheaper energy. Of course, we still don’t know the fate of China’s alternative bets on green technology and decarbonization. But for those of us who believe in some value of American leadership on the world stage, this is a rather dark period.”

You have studied how climate change can destabilize societies—fueling nationalism, mass migration, mental health crises—and you also discuss widening inequalities. Should these issues be priorities at COP30?

“Some of our projections are rapidly coming true in the form of individual disasters, such as the fires in Los Angeles. Indeed, the countries producing the largest number of migrants are usually those under climate pressure, which also leads to a shift toward authoritarianism, as we see in some Sahel countries with political destabilization. Yet there is also remarkable human resilience in the face of disasters—though sometimes accompanied by a lack of empathy and a shallow moral imagination. A meeting like COP must address the ‘normalization’ of climate chaos, which is increasingly seen as something ordinary in people’s mindsets.”

You describe how crop failures can threaten global food security. How do you think COP30 could respond?

“Warming is harmful to crops because it changes seasonal patterns, making areas that were optimal for certain crops unsuitable, while it is difficult to shift cultivation zones. Warming also affects weed and pest growth, and increases extreme weather events. Already, hundreds of millions of people are suffering needlessly from food insecurity. This isn’t happening because climate change has already reduced food quantities. In fact, every year we produce more food than the last. It happens because food production systems have become more unstable. And this instability is accompanied by financialization, which has proved catastrophic for the world’s poor.

As a result, levels of extreme hunger are rising even as global food productivity is higher. The global food system has become far less reliable, and food supplies that should be going to the world’s poor are more often being diverted to the wealthy.”