Egypt is emerging as a pivotal factor in the complex geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly in shaping the balance of power over the crucial issue of maritime zone delimitation, as well as in key areas such as energy, security, and migration. “The most populous Arab country remains a rare pillar of stability amid a series of deeply problematic situations — from the civil war ‘nightmare’ in Sudan, the de facto failed state of Libya, and the fragile truce in Gaza, to the risk of a resurgence of movements like the Muslim Brotherhood. Egypt also hosts several hundred thousand migrants within its borders,” a senior diplomatic source told To Vima, highlighting the special importance of President Sisi’s regime for Greek interests.

“Along with Saudi Arabia, Egypt serves as the main counterweight to Turkey’s ambitions to establish itself as a hegemonic power at the strategic crossroads between East and West,” the same source added.

Within this context — and despite the recent, nearly uncontrolled cooling of bilateral relations caused by the confiscation of lands belonging to the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai — Athens aims to further consolidate its partnership with Cairo as it explores the creation of a five-party cooperation framework in the wider region.

The Maritime Zones

Greece and Egypt are linked by their partial Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitation agreement of August 2020, which they regularly cite as a model of respect for the Law of the Sea and the principles of good neighbourly relations — in direct contrast to Ankara’s revisionist agenda in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Greek–Egyptian EEZ remains the only practical challenge to the Turkey–Libya memorandum, while a similar agreement had already been signed between Egypt and the Republic of Cyprus (2003–2004). However, the 2020 delimitation excluded areas east of the 28th meridian, which Turkey also claims — offering Egypt the argument that a bilateral deal with Ankara could grant Cairo a larger maritime area than any possible extension of the Greek–Egyptian agreement.

While Ankara has been persistently attempting to rebuild ties with President Sisi — partly due to a shared approach on the Palestinian issue — Athens remains calm. “The level of cooperation and mutual understanding with Egypt is extremely high. A bilateral settlement between Cairo and Ankara is out of the question,” close aides to Foreign Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis told To Vima, even as experienced legal officials acknowledge that some Turkish overtures to Egypt appear “tempting.”

Still, it did not go unnoticed that last summer Cairo issued a verbal note disputing part of Greece’s eastern continental shelf limits, as set out in its Maritime Spatial Plan — effectively suggesting that Greek islands do not enjoy full maritime effect. “In fact, in the 2020 agreement, Crete received only 5–7% effect, Karpathos even less, while Rhodes was not counted at all,” recalled a member of the Greek negotiating team at the time.

The Emerging Five-Party Framework

The question, therefore, is twofold: Can Athens prevent a Turkish–Egyptian understanding, and is an extension of the Greece–Egypt EEZ the best possible answer?

“A bilateral deal with Cairo for areas east of the 28th meridian is not on the horizon,” senior diplomatic sources told To Vima, adding that the proposed five-party cooperation format — championed by Athens — could reshape the landscape.

“If Turkey refuses to sit at that table, where maritime zones in the Eastern Mediterranean could be discussed, then bilateral negotiations may gain a different momentum,” the same sources noted. The goal, they stressed, is a comprehensive settlement based solely on the Law of the Sea — a principle consistently upheld by Greece, Cyprus, and Egypt, despite minor deviations already evident in their 2020 EEZ accord.

Officially, Foreign Minister Gerapetritis has yet to brief his Egyptian counterpart, Badr Abdelatty, on Greece’s five-party initiative — though he has done so with his Israeli and Turkish counterparts. Still, all indications suggest that Cairo will respond positively, maintaining its “wild card” position: it has internationally recognized agreements with Athens and Nicosia, has filed objections at the UN regarding its western maritime border with Libya, and remains in open communication with Ankara despite President Sisi’s enduring mistrust of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a known supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood — Sisi’s main domestic rival.

The two countries also share historical links rooted in their Ottoman past, with their bureaucracies traditionally maintaining steady channels of communication.

Incentives and Pitfalls

Cairo highly values Athens’ support for its €7.5 billion agreement with the European Commission, signed in March 2024 to bolster the Egyptian economy — with Greece consistently acting as Egypt’s gateway to Europe. So far, only €1 billion has been disbursed, amid European concerns over migration management. As Brussels often notes, “Egypt is too big to fail.” Aid to Cairo, therefore, is seen as a prerequisite for medium-term stability in one of the world’s most turbulent regions — a point Athens regularly underscores.

Just last week, on the sidelines of the EU summit, the EU–Egypt Conference reaffirmed both sides’ commitment to international law — particularly the Law of the Sea — as well as their respect for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all states in the region.

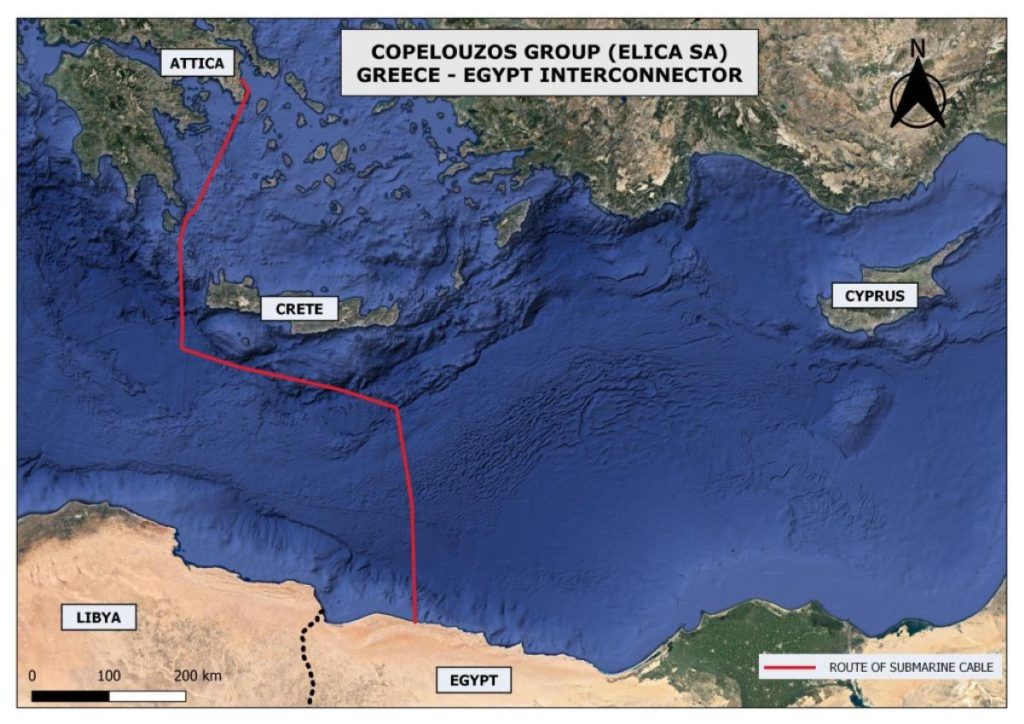

A distinct pillar of Greek–Egyptian and EU–Egyptian cooperation is energy. Athens and Cairo are advancing the GREGY electricity interconnection — one of the most ambitious projects in the Eastern Mediterranean. The initiative carries multiple layers: a “green” project under the EU’s energy independence framework, a geopolitical instrument reducing vulnerability to external interference (notably from Turkey), and an infrastructure link running through the jointly delimited EEZ.

By contrast, the issue of the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai remains a thorn in bilateral relations despite recent progress. “Until the documents are signed, nothing can be taken for granted,” officials closely involved in the matter told To Vima. Athens remains focused on safeguarding the monastery’s Greek Orthodox and religious character, as well as ensuring the long-term presence of the monastic community.

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ presence at the enthronement of the newly elected Abbot of Sinai, Father Symeon, was itself a symbolic act of support — a clear message to Cairo that Athens intends to keep a close watch on developments in Sinai.

Even if the decision of the Ismailia Court of Appeal on the monastery’s property rights came as an unacceptable — and nearly trust-shaking — surprise for Athens, what now matters most, Greek officials emphasize, is “to avoid any disturbance in the strategic relationship with Egypt.”