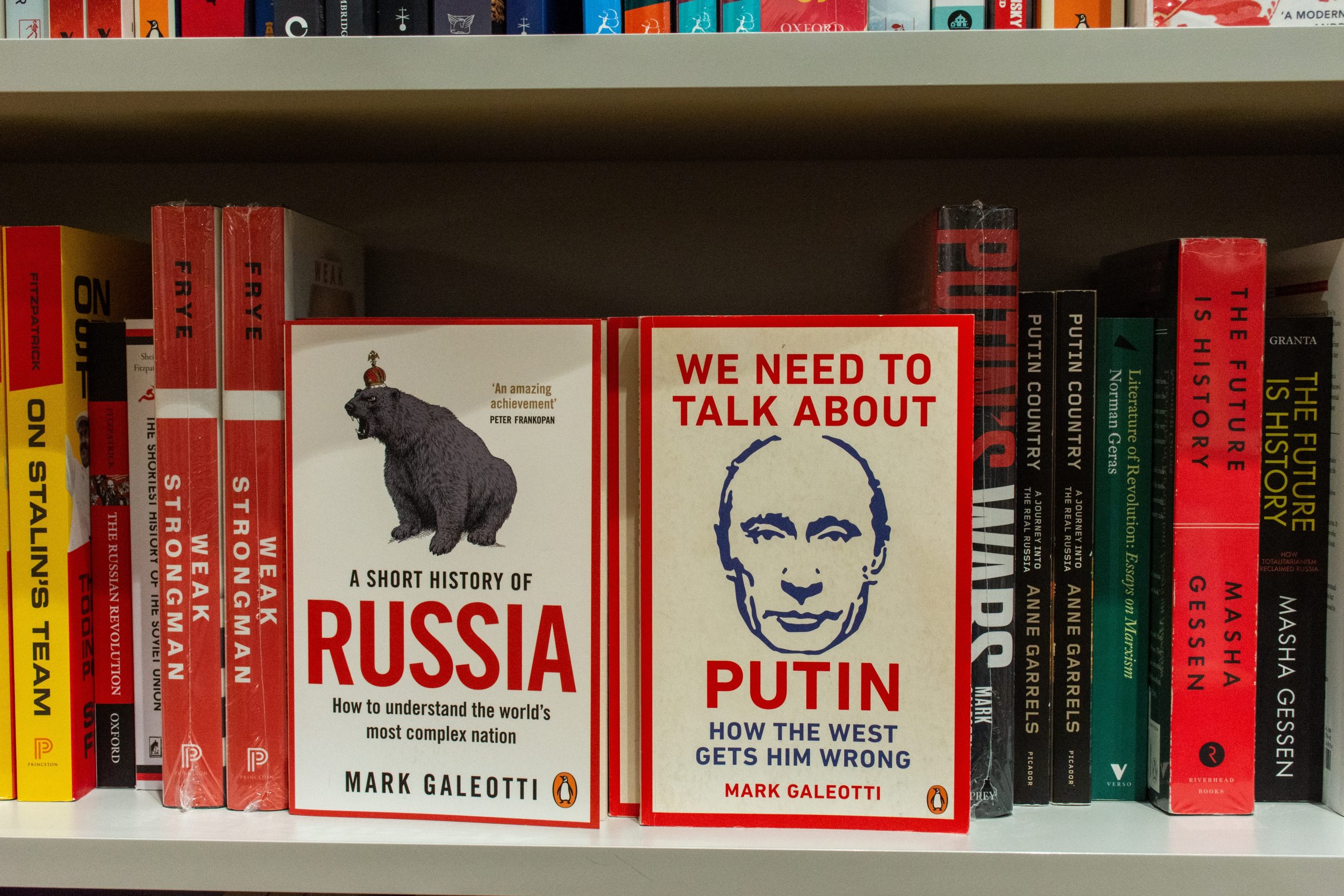

“To Βήμα” spoke with Mark Galeotti, professor of Slavic and East European Studies at the University College of London and scholar of modern Russian history, about the priorities of the Russian president in Ukraine. His book “A Short History of Russia” is published in Greek by Patakis Publications.

After the Trump-Putin meeting, expectations were raised about the prospect of peace in Ukraine. In your opinion, how willing are Kremlin and Putin to serve such an expectation?

I’m still not optimistic, but in truth Trump, in his clumsy and self-interested way, may have opened up a window of opportunity. Putin is under some pressure himself, especially as the Russian economy slides towards recession and the number of dead and wounded exceeds a million. Yet his position is not threatened, and if need be, Russia can keep fighting. After all, Putin believes he is slowly winning on the battlefield, and he doesn’t need to fight forever, just longer than Ukraine can.

So I think Putin is willing to sit back and see if he is offered a deal which suits him, which will allow him to trumpet his success in defying NATO and “saving” eastern Ukraine, although he wants the other side to make a move and signal a willingness to accept his terms. If that doesn’t seem to be on offer, though, he is also perfectly willing to walk away and keep fighting.

Trying to explain why Russia invaded Ukraine, some analysts focus on territorial gains, others emphasize the idea of Greater Russia, and there is also the view that Ukraine is being used as a bargaining chip to upgrade Russia’s role on the international stage. What do you think is true?

I think it’s a combination of factors. Putin has a very 19th-century, almost colonial view of geopolitics, and in particular he has strong views that Ukraine is both an artificial country (it has, after all, only been truly independent for little over a year 1918-20 and then since 1991) and rightly within Russia’s sphere of influence. He never really wanted to annex any of it, with the exception of Crimea (which had been Russian until 1954), but instead to remind it of its place and to prevent further integration into the West. His fear – an unrealistic one – was that it might join NATO, or at least end up being a base for NATO troops.

It was also a question of his own obsession with a historical legacy. Just as being the ‘tsar’ in whose reign Ukraine was ‘lost’ was something he could not bear, so too being the Russian leader who brought Ukraine ‘back’ would, in his eyes, be his crowning glory. Given that he mistakenly believed the Ukrainians would not fight but instead submit to Moscow imposing a puppet leader, he believed this was going to be a triumph that consolidated his place in history.

Many analysts talk about the transformation of the Russian economy into a war economy. Is such an approach justified, what is your impression?

Much of the Russian economy has indeed switched to a war economy – we have seen factories converted from civil to military purposes, and investment very much head that way. This has distorted the whole system, not least driving up wages offered in the defence sector, which is running 24/7, and leading to a labour shortage elsewhere. At present, more than 40% of the government budget is being spent on the military, some 8% of GDP.

That said, the irony is that for most Russians, life has scarcely changed. Unless you come from an impoverished region which provide most of the soldiers (who are, after all, volunteers, generally attracted by the huge bonuses and salaries being offered), everything seems pretty normal. The effects of the war are only creeping up on them: rising prices, sanctions, and so on.

You have covered extensively the power system that supports Vladimir Putin in your books. Is it still as strong today, after 3.5 years of war? And what kind of consensus does it draw from Russian society?

It’s very difficult these days to get a good sense of Russian public opinion. A majority genuinely want to see the war ended, but not at the cost of defeat. With the soldiers being well-paid volunteers, there is not the kind of public backlash there would be if conscripts were being sent to the front. Likewise, as I mentioned, the war and sanctions have not had a serious impact on most people’s lives.

That said, I do think Putin’s position has suffered. This is very much his war – there was no public clamour for it – and especially once the soldiers start coming home and the bloody truth about it becomes better known, there will be a backlash. Furthermore, many within the elite are concerned about the long-term costs, and the degree to which Putin is willing to burn Russia’s future in the name of this unexpected and unwelcome war. There is still no question of any serious threat to his position, not least because enough of the security apparatus is still loyal. But consider what happened when the Wagner mercenary army mutinied in 2023: very few joined the rising, but most of the army and security forces showed no interest in trying to stop it, either. Likewise, if there is some crisis that threatens Putin, I could see many within the elite sitting back and just seeing what happens.