The negotiations for a peace agreement in Ukraine are difficult; however, regarding Greece, they raise a secondary but inevitable question. If cheap Russian natural gas begins flowing again to Europe, what will become of the economic and geopolitical benefits of the vertical corridor and the agreements for American LNG? The government appears reassuring, believing that Europeans have learned their lesson and will no longer allow energy dependence on Russia. Specialists also point out that the vertical corridor was designed in 2015 and began implementation in 2017, meaning it was a strategic plan carried out by different governments; it simply happened that, due to current circumstances, its usefulness became more visible—and they insist that this usefulness will not be lost.

One of the key agreements at the P-TEC energy conference, held at Zappeion on November 6–7, was the one signed between the American company Venture Global Inc and the Greek Atlantic-See LNG Trade (DEPA and Aktor) for a 20-year LNG purchase agreement aimed at the markets of Central and Eastern Europe—the same markets targeted by the vertical corridor. Ukraine became the first among them, but there are also other countries such as Serbia, Hungary, Moldova, and others, which lack access to alternative energy sources.

The Upheavals

Significant shifts took place in 2025. U.S. President Donald Trump placed heavy emphasis on America’s energy sovereignty. On their part, Europeans reduced tariffs from 25% to 15% in exchange for purchasing military equipment and liquefied natural gas (LNG) worth 750 billion euros by 2028. These terms were part of the agreement announced on July 27 by Trump and Ursula von der Leyen.

The President of the Commission declared the agreement satisfactory, though she was criticized for its ambiguities and for Europe’s inability to stand firm against Trump. What appears like a noose for other European countries with large manufacturing industries turned into an unexpected opportunity for Greece—both for LNG transit and for exploration.

Already since mid-March, Minister of Environment and Energy Stavros Papastavrou, together with Deputy Minister Nikos Tsafos and the CEO of the Hellenic Hydrocarbon and Energy Resources Management Company Aristofanis Stefatos—a strongly U.S.-trained team reporting directly to Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis—began persistently cultivating the Greek government’s relationship with key figures in American energy policy, mainly with Doug Burgum, the head of the powerful National Council of Energy Sovereignty.

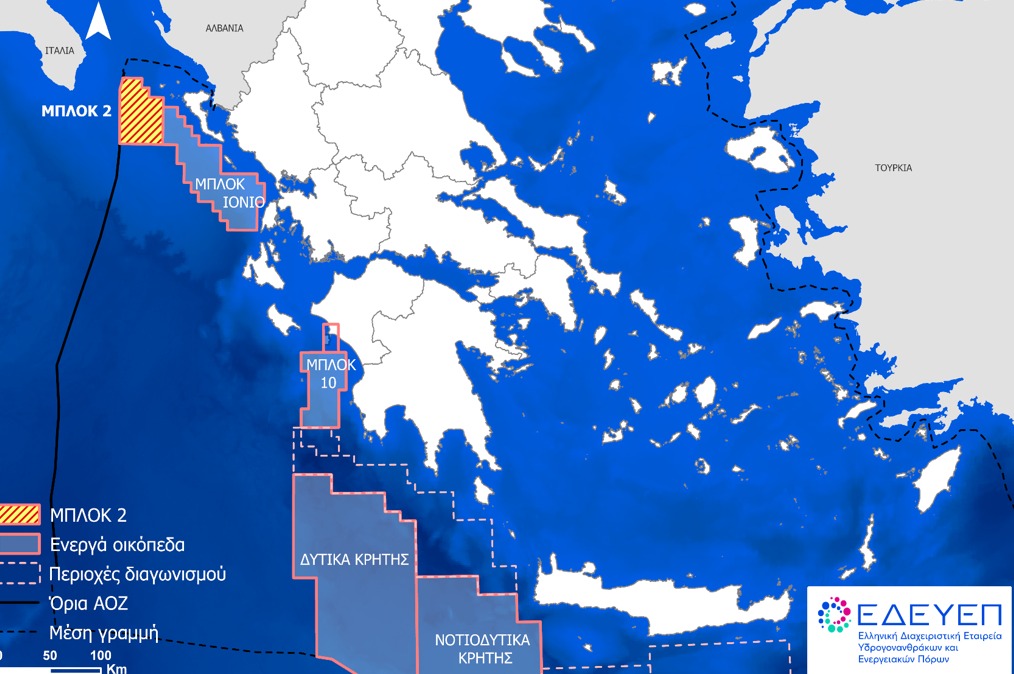

Chevron renewed its interest in hydrocarbon exploration south of Crete, but the relationship with Exxon Mobil went through many difficulties due to the company’s skepticism—both about Greece’s capabilities and about EU regulations and bureaucracy. The atmosphere was “numb,” from the team’s first meeting on May 9 with the company’s vice president, John Ardill, in Irving, Texas, until nearly September, when Exxon, together with HELLENiQ Energy, submitted a bid. To overcome obstacles, the government had to adopt a more energy-realist public narrative and demonstrate speed and efficiency in preparing the tenders.

Dependence or Not?

Naturally, the question arises whether Greece is becoming excessively tied to the United States. Government sources respond that “regarding natural gas, there is no long-term exclusive agreement, and our country can procure gas from other nations as long as it is not of Russian origin.” In any case, on October 20 the EU decided to completely detach from Russian natural gas by 2028. Concerning exploration, they explain that “the cost is so high—5 to 100 million euros for surveys and 5 to 10 billion euros for extraction—that only energy giants can undertake it, and in the Eastern Mediterranean the companies operating are Exxon and Chevron.”