From Vladimir Putin in Russia to the theocrats in Iran, authoritarian leaders are increasingly shutting down independent media and locking up reporters , with hundreds of journalists now in jail around the globe.

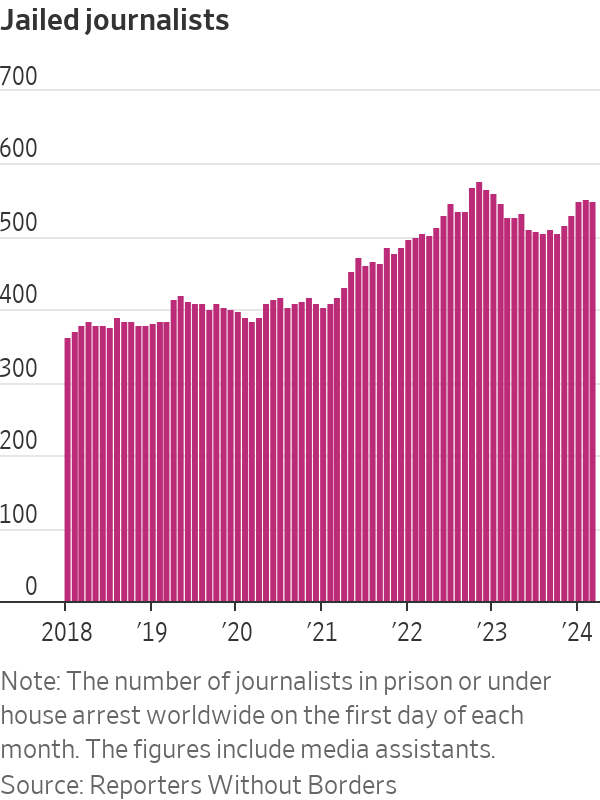

The surge in government crackdowns on the press, which accelerated after Russia invaded Ukraine two years ago, has left more than 520 journalists imprisoned worldwide, including a few dozen under house arrest, according to the Paris-based advocacy group Reporters Without Borders. The figure is among the highest the group has ever recorded.

The crackdowns reverse an expansion of media freedom that began after the end of the Cold War, as many governments turn toward autocracy. Even places that were once bastions of the free press, such as Hong Kong , are tightening restrictions on journalists. And countries such as Russia that once tolerated some dissent are imposing near-totalitarian limits on independent journalism, leaving state media and government propaganda to fill the void.

Many other journalists have been forced into exile under threat of imprisonment or worse, while authorities have banned numerous independent news outlets, forcing them to close or operate from abroad. New censorship laws restrict how journalists can cover topics deemed off-limits, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

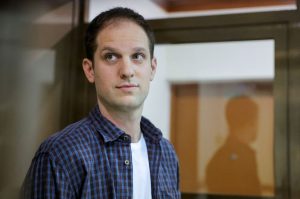

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that an agreement to release Evan Gershkovich is a possibility. PHOTO: REUTERS

“It is difficult to work knowing that at any moment the newspaper can be closed and journalists arrested without hope of a trial,” said Oleg Roldugin, editor in chief of Sobesednik, one of Russia’s last remaining independent newspapers. undefined undefined Russia is now one of the most dangerous places to practice journalism, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data collected by Reporters Without Borders. Nearly three dozen journalists are in Russian prisons, among the most of any country. That puts Russia ahead of Saudi Arabia and Syria and behind only China, Myanmar, Belarus, Israel and Vietnam, according to the data. Globally, around 600 journalists have spent time in prison or under house arrest so far this year.

The figures show Israel arrested the most journalists in 2023, and is now holding 35, after it detained dozens of reporters in the Palestinian territories following the deadly Hamas attack on Oct. 7. Reporters Without Borders doesn’t list the reasons for their arrest. Israel doesn’t say why these people were arrested.

Reporters Without Borders said Israeli forces have killed 21 journalists covering the ground offensive in the Gaza Strip, making the Palestinian territory the world’s most deadly place for reporters this year and last. The advocacy group says its investigations suggest seven of the journalists were explicitly targeted by Israeli forces or killed while identifiable as journalists. It has filed a complaint with the International Criminal Court over their deaths. At least 83 other journalists have been killed in the Gaza Strip during the war; the advocacy group is investigating whether their deaths were linked to their reporting.

Israel’s military, known as the Israel Defense Forces, said it “takes all operationally feasible measures to mitigate harm to civilians including journalists. The IDF has never, and will never, deliberately target journalists.”

Mexico is the second-deadliest country for journalists, with four killed last year and 11 in 2022. Reporters in Mexico often face violent reprisals from drug cartels, gangs and even local officials. The Mexican government didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“The number of countries witnessing a decline in media freedom has more than tripled during the last decade,” said Marina Nord, research fellow at the V-Dem Institute, a Swedish academic group that monitors treatment of journalists, censorship laws and other indicators to track broad shifts in democratic values. “This is a worrying trend, because attacks on media freedom are a strong indication that other democratic freedoms are in danger.”

The imprisoned journalists stand accused of a range of crimes—including espionage, incitement, spreading misinformation and terrorism—that press-freedom advocates say are designed to silence dissent or punish reporters who have exposed official wrongdoing.

Some have been detained for what appear to be geopolitical reasons. Putin has said that Wall Street Journal Reporter Evan Gershkovich , a U.S. citizen who has been held in a Moscow jail for a year, could be part of a prisoner exchange, “but we have to come to an agreement.”

Gershkovich is being held on an allegation of espionage that he, the Journal and the U.S. government vehemently deny.

The 32-year-old reporter was accredited by Russia’s Foreign Ministry when he was taken by officers from Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, during a reporting trip in Yekaterinburg on March 29 last year.

The U.S. has said Gershkovich isn’t a spy and has never worked for the government. The Biden administration has classed him as wrongfully detained, a designation that commits the U.S. government to work for his release.

Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, who is in custody on espionage charges, stands behind a glass wall of an enclosure for defendants as he attends a court hearing to consider extending his detention in Moscow, Russia, March 26, 2024. Moscow City Court’s Press Office/Handout via REUTERS

The journalist Alsu Kurmasheva, a dual U.S.-Russian citizen who works for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, is also detained in Russia. The U.S. hasn’t reached a decision on whether she has been wrongfully detained. Kurmasheva was taken into custody in October and charged with failing to register as a foreign agent. She also faces charges related to a book she edited that is critical of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Through her husband and legal team, Kurmasheva has denied the charges. The State Department says Russia has brought baseless charges against her.

Most of the world’s imprisoned reporters are local journalists who don’t have a foreign government working on their behalf. Many are freelance reporters or independent bloggers. undefined undefined The Kremlin has passed a suite of laws that attempt to quash opposition to its war in Ukraine. Many of the 34 journalists in Russian prisons are there because of their reporting on the conflict, according to Reporters Without Borders. Russia has outlawed the use of the words “war” or “invasion” to describe what the Kremlin calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine.

This month, Roman Ivanov, a reporter for the independent news website RusNews, was sentenced to seven years in a penal colony for several posts on social media and his Telegram channel that described alleged human-rights violations and war crimes by Russian forces in Ukraine. One post summarizes a United Nations report that found the Russian army committed war crimes, including executions, rape and torture, during the first months of the invasion. A court near Moscow convicted Ivanov of spreading “fake news” about the Russian army.

His sentencing was guarded by special-forces soldiers and a battalion of police “so dense that the batons were knocking against each other,” according to a report by Sobesednik, the independent Russian newspaper.

When the judge asked Ivanov if he understood the verdict, Ivanov replied, according to Sobesednik: “This is a verdict on you!” undefined undefined The Kremlin’s censorship laws forced much of the staff of Novaya Gazeta, Russia’s most celebrated independent newspaper, into exile in Latvia in April 2022. The newspaper set up a separate entity there called Novaya Gazeta Europe, which Russia has since declared “undesirable.” Russians working for it face fines or imprisonment. undefined undefined Still, the original Russian entity continues to publish, its reporting muzzled by the new laws and its print license revoked by the government, meaning it can’t publish more than 999 copies of each edition.

Sobesednik put Alexei Navalny on its front page after the prominent Kremlin critic died in a Russian prison in the Arctic last month. Authorities confiscated all copies of the paper around Moscow and have repeatedly blocked the newspaper’s websites, said Roldugin, the paper’s editor in chief.

“I think they want us to get scared and shut ourselves down. I will not say that we are completely calm, but we do not intend to close ourselves yet,” Roldugin said.

The Russian newspaper Sobesednik shows a photo of the late Alexei Navalny on the front page. PHOTO: MAXIM SHEMETOV/REUTERS

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov dismissed the suggestion that Russia is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist.

“There are many truly dangerous countries in the world for journalists,” he said in an email to the Journal.

Peskov said that in connection with Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine, “we now have very strict legislation regarding the sphere of information, but these laws are clear and precise. Those who violate them are punished.”

Moscow’s censorship policies are echoed and even amplified in other post-Soviet states. In neighboring Belarus, Russia’s closest ally, there are now 41 journalists locked up on a range of charges, such as defamation of President Alexander Lukashenko or membership in an “extremist” group—usually a foreign media outlet that has been banned by the government. In Kyrgyzstan, authorities this year arrested 11 journalists from the investigative outlet Temirov Live. Kyrgyzstan has also opened a probe into the investigative website 24.kg, after Russia’s media regulator sent a letter to the outlet in 2022 telling it to delete articles about the war in Ukraine and then blocked access to the site from Russia.

“The situation is getting worse and worse in central Asia, and we see that there is Russian pressure behind it,” said Jeanne Cavelier, head of the Eastern Europe & Central Asia desk at Reporters Without Borders.

The governments of Belarus and Kyrgyzstan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Iran releases two

Protest movements in the Muslim world have led to sharp crackdowns in recent years. Iran has arrested more than 70 journalists since the death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of Iran’s morality police, which detained her for allegedly not wearing the Muslim headscarf. The 22-year-old’s death in 2022 sparked widespread protests and violent reprisals by the Iranian authorities.

Niloofar Hamedi and Elaheh Mohammadi, two journalists who were among the first to report on Amini’s death, were arrested in 2022 and charged with collaborating with the U.S. Both have denied the charges and were released on bail in January after spending 17 months in prison. Twenty journalists are currently imprisoned in Iran, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Iran’s ambassador to the U.N. didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Algerian government has closed independent news outlets and jailed several high-profile journalists in the wake of a protest movement that arose in 2019 to demand more political freedom. Ihsane El Kadi, the founder and editor in chief of two of Algeria’s leading privately owned media outlets, was arrested in December 2022 and charged with receiving foreign financing to undermine national security.

El Kadi denied the charges, saying he received money from his daughter in London to help keep his media outlets operating. El Kadi was a critic of Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune , who called him an “informer” on national television after his arrest. He was sentenced last year to seven years in prison. undefined undefined “He covered subjects that could potentially destabilize the powers that be, and they made him pay dearly,” said Pierre Brunisso, a Paris-based lawyer who represents El Kadi.

The Algerian government didn’t respond to a request for a comment.

China holds the most

In Asia, Vietnam and Myanmar have become among the world’s most prolific jailers of journalists. Myanmar has imprisoned dozens of reporters since a military junta took control of the country in 2021. There are 35 journalists currently imprisoned by authorities in Vietnam.

The government of Communist-ruled Vietnam didn’t respond to a request for comment. Myanmar’s embassy in Washington said some of the journalists were arrested for “their unlawful activities prevented by the existing laws and regulations of a sovereign country so as to maintain law and order, not for their media reporting. But media persons should abide by the laws of Myanmar, and no one is above the law.”

Henry Tong, an exiled Hong Kong activist who is currently living in Taiwan, tears apart a cardboard with 23 on it, during a protest against Hong Kong’s Article 23 national security law in Taipei, Taiwan March 23, 2024. REUTERS/Ann Wang

China holds the largest number of journalists—more than 100—in its jails, a spot it has occupied for much of the last two decades. Many were detained during Beijing’s crackdown in Xinjiang province starting in 2014. Hong Kong has tilted toward Chinese-style policies after Beijing passed a national-security law for the city in 2020.

Authorities say the law is necessary to maintain public order after protests swept the territory in 2019, but critics say it is being used to silence independent journalism and political dissent. This month, Hong Kong passed a new national-security law that press freedom advocates say could impose greater limits on independent journalism.

A spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in Washington said China’s constitution guarantees freedom of speech and publication.

“Everyone is equal before the law and no one is allowed to break the law with any excuse,” said the spokesman, Liu Pengyu, adding that the U.S. should “stop pointing fingers at China’s press freedom.”

Write to Matthew Dalton at Matthew.Dalton@wsj.com and Jack Gillum at jack.gillum@wsj.com