‘You’re just scum” is probably as fitting an apothegm for our current state of political discourse as “It’s morning again in America” was almost 40 years ago.

Nikki Haley’s expression of exasperation with her sedulously repellent rival Vivek Ramaswamy at last week’s presidential debate captured well the low, dispiriting quality of post-Reagan American politics.

Scum was her spontaneous description of Mr. Ramaswamy. Others can probably think of appropriate but even ruder ones.

A long, long time ago, in 2022, Mr. Ramaswamy was a promising arrival on the political scene, a youthful and gifted entrepreneur with a classic American success story, ready to put his many talents at the disposal of the American people. I interviewed him several times and was impressed. He wrote passionately on these pages and elsewhere about reversing the retreat from the American values of political and economic freedom. But his performance on the campaign trail and in debates has betrayed that promise. Last week he capped a yearlong descent into the gutter by seeking political advantage in publicly rebuking another Republican for her parenting skills.

The transformation of Mr. Ramaswamy from brilliant young outsider of principled views and fresh energy to a parody of the most cynical, self-promoting and calculating opportunist is thus complete: from George Bailey to Elmer Gantry in less than 12 months.

But the real question is whether he has read the tenor of American politics better than others—or whether there is still hope.

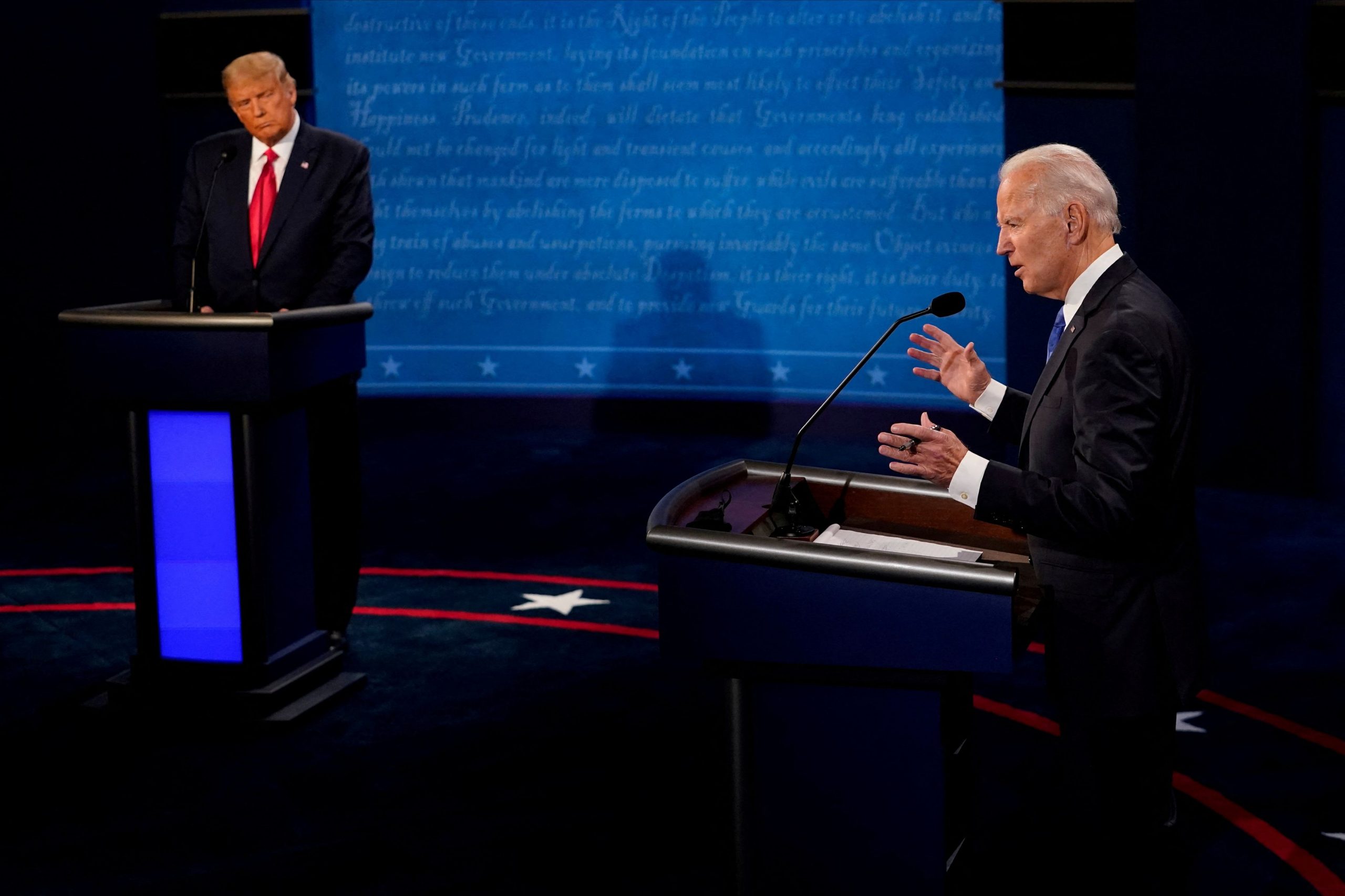

There remains a narrow path away from the national tragedy of a 2024 rematch between Donald Trump, Mr. Ramaswamy’s role model in nastiness, and Joe Biden, a palpably incapable incumbent staring into the abyss of senility.

On the Republican side, while Mr. Trump retains a huge lead, the dreamers can still see a way he can be unseated. State polls in Iowa and New Hampshire give him a smaller advantage than national surveys. Somehow, if the remaining no-hopers would accede to the inevitable, maybe Ron DeSantis and Ms. Haley between them could deliver a double blow to the former president in the first two primary contests in Iowa and New Hampshire, and then one—presumably Ms. Haley, given that her home state of South Carolina is next—could emerge as the clear challenger to a front-runner who by that time will be appearing in more courtroom dramas than Perry Mason.

It still sounds like a bit of a long shot. And on the Democratic side, similar dreams that Mr. Biden might step aside for a more plausible alternative also seem far-fetched—not least because of the absence of a plausible alternative.

But the dream lives on—and moves on to Plan B: a third-party candidate who might save the nation.

That a very large number of Americans are hungry for some alternative from the seemingly inevitable is not in dispute. It’s telling that somewhere between 10% and 20% of those polled say they will vote for Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a famous name. But he’s peddling conspiracy theories and quackery, disqualifying him as a genuine alternative.

So inevitably other names surface. Last week Joe Manchin set the dovecotes fluttering with his announcement that he won’t run again for his West Virginia Senate seat.

There’s much to like about Mr. Manchin. He seems to be the authentic Regular Joe, as distinct from the ersatz one who occupies the White House. He has crossover appeal. In 2018 he won re-election as a Democrat in a state Mr. Trump won twice by around 40 points—though it’s probably important to note (and germane to his decision to step down) that recent polls had Mr. Manchin losing re-election heavily. For a Democrat he talks sense about American energy supply, economics, national security and political culture, though he went along with a deficit-exploding fiscal package that went by the Orwellian name of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The possibility in our current political moment is a strange inversion from the last time a serious third-party contender ran. In 1992, the two main party candidates were both, for all their flaws, plausible and mainstream political figures. Bill Clinton was the New Democrat who had repudiated much of the unelectable left-wing extremism of his party in the 1970s and 1980s. He might have campaigned promising a big stimulus, but he reversed course and governed on fiscal prudence. George H.W. Bush was the model of genteel moderate Republicanism, a successful president ambushed by a brief moment of national angst.

Yet Ross Perot, campaigning on the single issue of deficit reduction, might have done even better than his 19% he got if he hadn’t—thanks to a weird and apparently paranoid grudge against the Bush family—seemed just too unorthodox for the presidency.

In 1992 then we had two main party candidates who essentially campaigned and governed from the center, almost bested by a third-party eccentric focused on a single issue.

This time around we have two main party candidates who in their different ways are outside the historical mainstream, unorthodox and extreme, and a potential third-party candidate who embodies a craving for orthodoxy. If the third party came as close as it did in 1992, could it get even closer in 2024?