ADZOPÉ, Ivory Coast—In the central clearing of a steep-sloped cocoa plantation, surrounded by trees dripping with fat green pods, Brice-Armel Konan raised his smartphone toward the sky and saved the coordinates of his location in an app.

The farm, he calculated, was 1.4 miles from the nearest forest. “This one should be low risk,” he said.

It’s a scene being repeated across the West African nation of Ivory Coast, the world’s largest cocoa producer, as it embarks on a gargantuan experiment meant to make chocolate more sustainable. Its success will determine whether chocolate will become more expensive, on top of some of its highest price increases in the U.S. in recent years.

At the center of these efforts is a new European Union law that seeks to protect the world’s rainforests, which have shrunk dramatically in recent decades due to the expansion of land used to grow cash crops like cocoa, palm oil and coffee, or to herd cattle. Because the EU is the world’s largest chocolate market, importing more than half of the world’s cocoa beans, the law will also apply to global confection giants like U.S.-based Mars, the maker of M&M’s, or Switzerland-based Nestlé.

Starting from Dec. 30, chocolate makers that sell or produce in the EU will have to show that the cocoa they use wasn’t grown on land cut from forests since the end of 2020. In practice, it means that each morsel of cocoa that makes its way into the bloc will need to be linked to the GPS coordinates of the farm where it was harvested.

That’s where people like Konan, who helps monitor cocoa farm data in Ivory Coast for the Rainforest Alliance, a nonprofit based in New York and Amsterdam, and his smartphone come in. Such nonprofits, along with industry groups, governments and chocolate companies, are racing to help farmers record the data they need in time.

Ivory Coast’s cocoa and coffee regulator says it has mapped just over 80% of the country’s estimated 1.55 million cocoa farms. That leaves some 300,000—or about 2,000 a day—to be mapped or otherwise accounted for by Oct. 1, the start of the new cocoa season.

“You walk a lot. In the heat. Sometimes in the rain,” said Konan, an agricultural technician by training whose grandfather farmed cocoa and coffee. “Sometimes you have no signal.”

Confusion reigns

The EU initiative is part of a growing movement to make raw materials—including agricultural products and minerals used in smartphones and electric cars—traceable, with the goal of reducing the potential harm they inflict on the environment and local populations.

Ivory Coast was once covered in dense rainforest. But over the past 60 years, 90% of the country’s forest cover has disappeared, making it one of the countries with the highest annual rates of deforestation in the world over that period, according to the United Nations.

Ivory Coast and neighboring Ghana, the world’s No. 2 cocoa producer, are both working to stem the loss of forest cover.

In 2017, on the sidelines of a U.N. climate conference in Germany, the two governments signed a plan with some of the world’s largest cocoa and chocolate companies to halt the clearing of forests for cocoa production and restore areas that had already been degraded.

Since then they have worked to map cocoa farms—many of them mom-and-pop operations with less than 5 acres—along with organizations like the Rainforest Alliance, which has offered its own, separate certification process in Ivory Coast since 2009.

By 2022, the 36 signatory companies, which account for 85% of global cocoa use, said they had mapped 567,264 farms in Ivory Coast and were able to trace about 85% of their directly sourced beans in Ivory Coast and Ghana.

That effort doesn’t translate easily to the EU initiative. There is no central database for the various mapping initiatives. Some farms may have been mapped multiple times while others have never had their coordinates recorded.

A worker transports a bag of sun-dried cocoa beans at a warehouse in Kwabeng in the Eastern Region, Ghana, February 28, 2024. Long the world’s undisputed cocoa powerhouses accounting for over 60 percent of global supply, Ghana and its West African neighbour Ivory Coast are both facing catastrophic harvests this season. REUTERS/Francis Kokoroko/File Photo

Another snag is the level of detail of the required GPS longitude and latitude coordinates. The EU deforestation legislation requires cocoa farms to provide GPS coordinates that have at least six digits after the period, such as 6.113647, -3.850584. Previously, farmers and organizations under the Rainforest Alliance’s certification program shared GPS coordinates with only four decimal points.

That means potentially tens of thousands of farms that have been mapped will have to be mapped again—quickly.

“We did this job in three years,” said Jean-Marc Gouda, a team manager at the Rainforest Alliance. “The challenge is to tell them to do it again in six months.”

The EU also requires larger farms to submit GPS coordinates of their entire borders, rather than just a single point within the farm, and provide a digital representation of the farms’ boundaries. Officials say they might use satellite images and on-the-ground inspections to check the supplied data is accurate.

Many farmers are only now finding out about the new EU requirements.

Even if the mapping is completed in time, the system where companies will need to upload the GPS data is still under development, raising concerns over a last-minute scramble to log millions of coordinates.

The Ivorian government has said it would be ready to comply with the EU law in time. Still, at a global cocoa conference in Brussels last month, industry groups urged the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, to delay implementation of the new law.

“This regulation will have a cost,” said Michel Arrion, chief executive of the International Cocoa Organization, which represents 52 cocoa-importing and exporting countries. “There will be a lot of documentation and bureaucracy.”

Speculators pile in

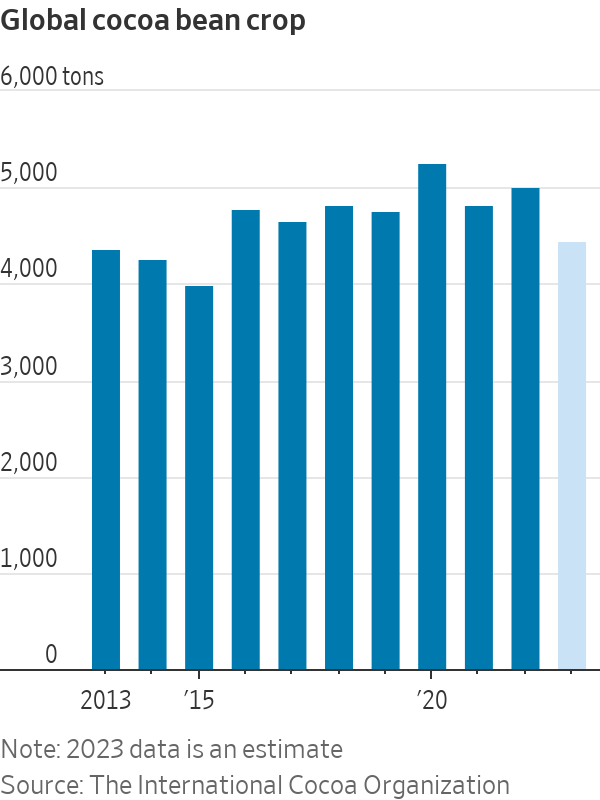

For consumers, the EU law couldn’t have landed at a worse time. Unseasonably hot and dry weather during the rainy season and wet weather during the dry season as well as cocoa-tree diseases have hit harvests across West Africa, the source of 70% of the world’s cocoa beans. Stockpiles this season are expected to be the lowest in 45 years, as demand outstrips supply for a fourth consecutive season.

Hedge funds and other speculative traders have piled into the market, betting that shortages would send prices higher. Net long positions in cocoa futures—or bets that prices will rise—were at their highest in about a decade at the end of January, according to data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Prices for cocoa recently touched a record high of nearly $11,500 a metric ton on the futures market in New York, about four times as high as they were a year ago and more than double the previous record of about $5,400, set in 1977.

Chocolate companies including Mondelez International and Lindt & Sprüngli have already warned that they will have to lift prices further this year. Those increases, which Mondelez said could reach double digits, will come on top of a 12% rise in the price of U.S. chocolate candies in 2023 and a 14% increase in 2022, according to data from Circana, a Chicago-based market-research firm.

In times of high prices, companies also often shrink the size of their products or tweak recipes to use less cocoa.

Farmers have traditionally responded to cocoa shortages by clearing forests to make way for more farmland. That’s not an option under the new EU legislation.

Failure to map all the farms in Ivory Coast and other cocoa-producing countries could take more beans out of the market, worsening the shortages.

“This is the Titanic heading towards the iceberg,” said Edward George, founder of London-based Kleos Advisory, which advises investors on African commodities markets. “There’s a full-on crisis. Prices could remain painfully high.”

Mapping risk

Cocoa currently accounts for 10% of Ivory Coast’s GDP and 25% of jobs, said Finance Minister Adama Coulibaly.

Growing cocoa is done almost completely by hand, with the aid of a machete. A 2021 study by Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands showed that between 30% and 58% of cocoa farmers in Ivory Coast and Ghana earned a gross income below the World Bank extreme poverty line, which at the time was $1.90 a day.

Farmers have only just begun to see the benefit from higher prices, because the Ivorian and Ghanaian governments sell crops a year ahead of time. On April 2, Ivory Coast raised the price it pays farmers by 50%, to 1,500 West African CFA francs ($2.49) a pound. Ghana raised its prices by 58% a few days later.

The farm that Konan of the Rainforest Alliance remapped is part of Société Coopérative Agricole Adzopé Nord, or Socaan, a cooperative that sells to cocoa-trading and processing giant Cargill. It has about 3,400 members in and around the town of Adzopé, and produced about 7,000 metric tons of cocoa during the season that ended Sept. 30.

At Socaan’s offices recently, Konan and Adou Adou Constant, the cooperative’s head of sustainability, studied maps covered in dots that represent member farms. Most of the dots were green, meaning there was low risk of deforestation or encroachment on a protected area. There were a couple of orange dots, for medium risk.

Brice-Armel Konan of the Rainforest Alliance records the GPS coordinates of a cocoa farm on his phone. PHOTO: ALEXANDRA WEXLER/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The few clumps of red dots were closest to forests or protected areas, indicating high risk. Socaan sends representatives to those areas for additional on-the-ground monitoring, as well as education about deforestation.

Constant says around 93% of member plantations are mapped and part of a certification program, like Rainforest Alliance. New members provide GPS coordinates to the co-op, often using smartphones donated by Cargill.

“The mapping is a challenge,” Constant said.

On benches lined up under trees in front of the offices of Société Coopérative Fraternité d’Adzopé, or Scafra, another cooperative in Adzopé, about two dozen farmers gathered to hear from the Rainforest Alliance’s Gouda as he explained the need for their plots to be remapped to six digits.

“Don’t be afraid,” he said.

None of the farmers present at the meeting had heard about the new EU requirements to combat deforestation. Some worried that more onerous regulations would continue to surprise them and create more work.

“We are worried about a policy that is going to start in six months, and at the same time, we don’t have any details on what we need to do,” said Kpomin Minrienne Kole Edi, the chief executive of Scafra.

To increase their harvests now, farmers will have to invest more in things like fertilizer and pesticides, industry experts say. And instead of simply clearing new land for crops, farmers will have to use good agricultural practices like pruning and replacing aging trees with new seedlings. To motivate farmers to do that, industry experts say, cocoa prices need to remain higher for longer.

“Nobody really expects the price to go down quickly anytime soon,” said Antonie Fountain, managing director of the Voice network, an association of civil society organizations working in sustainable cocoa based in the Netherlands. “The sector is finally at the point where we’re acknowledging that we need to pay more for sustainable cocoa.”

Write to Alexandra Wexler at alexandra.wexler@wsj.com