When she disappeared on her most ambitious trip—what she hoped would be a record-setting journey around the world—it sparked a decadeslong mystery: What happened to Amelia Earhart?

Now, a commercial real-estate investor from Charleston, S.C., thinks he might have found a vital clue.

Tony Romeo, a pilot himself and a former U.S. Air Force intelligence officer, is the latest in a string of adventurers to plumb the Pacific Ocean in search of the plane Earhart was flying in 1937 when, at the peak of her fame, she vanished.

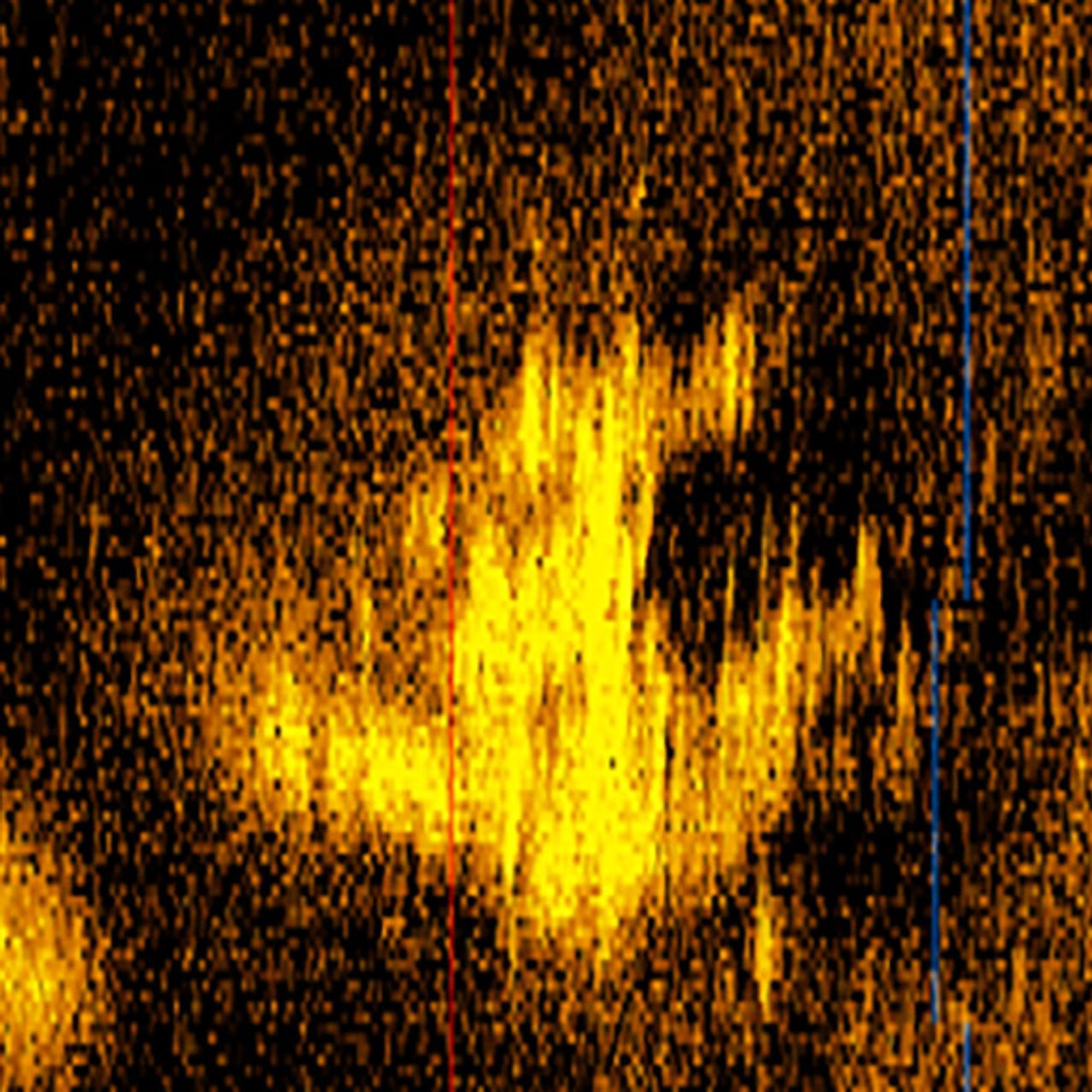

In December, Romeo—who sold his commercial properties to fund his search—returned from an expedition with a sonar image of an aircraft-shaped object resting on the ocean floor. He believes it’s Earhart’s Lockheed 10-E Electra, and experts are intrigued.

The location where Romeo said he captured the image is about right, said Dorothy Cochrane, a curator in the aeronautics department of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, and sonar experts who have viewed the image agree that it’s unusual enough to take a closer look.

Romeo said he plans to return to get better images. “This is maybe the most exciting thing I’ll ever do in my life,” he said. “I feel like a 10-year-old going on a treasure hunt.”

At the dawn of the modern aviation age, Earhart’s record-breaking run as a pioneering pilot made her an international celebrity. She was the first woman to fly solo, nonstop across the continental U.S. and the Atlantic, and the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to the mainland over the Pacific.

“For her to go missing was just unthinkable,” Romeo said. “Imagine Taylor Swift just disappearing today.”

Since Earhart vanished, voyagers on at least a half-dozen trips have sunk millions into hunts for her lost plane.

People can’t quit Amelia. They also can’t seem to find her.

In 1999, Dana Timmer, an America’s Cup sailor, helmed a deep-water search near Howland Island, a dot of land between Australia and Hawaii where Earhart was last expected to land. Timmer saw a promising shadow on sonar, but never raised the cash to go back and verify his find.

In 2009, a team put together by Ted Waitt, founder of the Gateway computer company, hauled in a handful of junk including a metal drum and a 6-inch-wide cable. “We’re confident we know where #Earhart isn’t,” the group tweeted after the expeditions.

Nauticos, an ocean exploration firm, launched three searches, in 2002, 2006 and 2017, but found nothing but a piece of pipe and other shipping trash, said David Jourdan, the company’s president and founder.

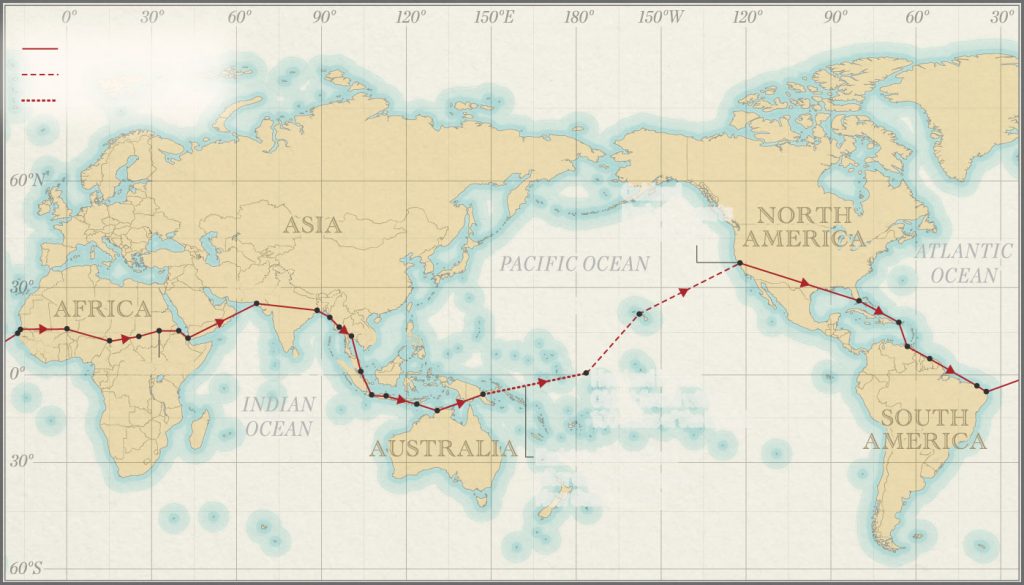

Fateful Flight

For years adventurers have searched the Pacific Ocean along the final stretch of Amelia Earhart’s flight route in hopes of finding her missing plane.

Note: Flight path is simplified.

Sources: Smithsonian Institution (Oakland departure); Sammie L. Morris, Purdue University (Miami to Oakland route)

Emma Brown/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“It’s the only thing in my career that I’ve ever looked for and not found,” said Tom Dettweiler, a sonar expert who participated in two of the Nauticos searches and was part of the team that found the Titanic off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, in 1985.

Excluding the Waitt group, which declined to disclose costs to the Journal, the missions collectively cost at least $13 million when adjusted for inflation.

Romeo and two of his brothers, all pilots, thought they’d bring their airmen’s read to “the perfect riddle” of where Earhart disappeared. “We always felt that a group of pilots were the ones that are going to solve this, and not the mariners,” Romeo said.

They tried to imagine Earhart’s strategy by drawing on clues about her direction, location and fuel levels based on radio messages received by Itasca, the U.S. Coast Guard vessel stationed near Howland Island to help Earhart land and refuel. Then Romeo and his team plotted a search area based on where they thought Earhart was most likely to have gone down.

Romeo said he sold his real estate interests in 2021 and spent $11 million to fund the trip and buy the high-tech gear needed for the search—including an underwater “Hugin” drone manufactured by the Norwegian company Kongsberg.

“That’s the vehicle I would choose to use,” said Larry Mayer, an oceanographer and director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire.

Romeo’s expedition began in early September from Tarawa, Kiribati, a port near Howland Island, with a 16-person crew aboard a research vessel.

In outings that lasted 36 hours each, the unmanned submersible scanned 5,200 square miles of ocean floor. About 30 days in, it had captured a fuzzy sonar image of an object the size and shape of an airplane resting some 5,000 meters underwater within 100 miles of Howland Island. But the team didn’t discover the image in the drone’s data until about 90 days into the trip. By then, it wasn’t practical to turn back, Romeo said.

Experts who have seen the image said they want to see clearer views of the object with details such as a serial number that matches Earhart’s vessel.

“Until you physically take a look at this, there’s no way to say for sure what that is,” said Andrew Pietruszka, an underwater archaeologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California, San Diego, who leads deep ocean searches for lost U.S. military aircraft and the soldiers who went down with them.

The search for Earhart’s plane is particularly challenging because of the remoteness of her last known location. “It’s very deep water, and the area that she could’ve possibly been in is huge,” Dettweiler said.

This was also Earhart’s challenge.

On July 2, 1937, she and navigator Fred Noonan took off from Lae, Papua New Guinea, nearing the end of their historic trip. They planned to refuel at Howland, an uninhabited island where a runway and refueling station had been built ahead of their arrival, before flying on to Honolulu and finishing in Oakland, Calif.

The world was watching.

Earhart and Noonan took off from Lae into a strong headwind. Operators listened to Earhart’s radio messages as she flew across the Pacific toward Howland, a half-degree north of the equator. The Coast Guard’s Itasca, stationed near the island, estimated their progress by the strength of the radio transmissions.

The last messages came in so strong that a radio operator looked skyward, expecting to see her fly overhead, according to Laurie Gwen Shapiro, a journalist who is working on a biography of Earhart.

She was nowhere to be seen.

After 16 days, the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ended their search, and on Jan. 5, 1939, Earhart was declared dead.

Most experts who have studied Earhart’s last broadcasts expect to find her craft within range of Howland Island, but in the absence of its discovery, a host of theories have emerged. In one improbable scenario, Earhart was captured by a foreign military. In another, she made a secret return to the U.S. and lived a quiet life out of the spotlight under a new name. In a third, she was a spy.

“That’s just nonsense,” said Cochrane, the National Air and Space Museum curator. “None of that is practical.”

For now, the world is still waiting for an answer.

“It was one of the great mysteries of the 20th century and still now into the 21st century,” Cochrane said. “We’re all hopeful that the mystery will be solved.”

Write to Nidhi Subbaraman at nidhi.subbaraman@wsj.com