KYIV, Ukraine—At the end of a bare concrete hallway, in a building that sat empty until a few months ago, a dozen men hunched over desks assembling pieces of black carbon fiber and soldering on computer chips. A gyroscope whirred, testing the final product: an explosive attack drone.

This workshop in western Ukraine is one of dozens of startups producing cheap weapons that are helping Ukrainian troops against the Russians. Short on ammunition with additional military aid from the U.S. stalled, Ukraine is trying to compensate by producing an army of a million explosive FPV, or first-person-view, drones.

The country lacks a modern arms industry that can sustain the war effort, and it would take years—and billions of dollars—before Kyiv could produce the kind of artillery and missile systems it needs on a large scale.

But drones—which can be assembled from parts available on the commercial market and cost just a few hundred dollars each—are comparatively cheap and easy to produce. Makeshift factories are now popping up all over Ukraine and churning out thousands of FPV drones each month.

The drones are then delivered to the front, where soldiers attach explosives and fly them into Russian trenches and armored vehicles. They are guided by an operator using a controller and wearing goggles that let him see what the drone’s camera sees.

“With our economy, we cannot make tanks,” said Mykola Havryluk, chief executive of Sparrow Avia, a drone-production company. “Our solution is to make drones.”

With Ukraine now on the defensive, after last summer’s counteroffensive failed to make a substantial breakthrough, FPV drones have become crucial in Kyiv’s efforts to hold the Russians back. The drones can’t do as much damage as artillery shells or mortar bombs, which are now in short supply. But Ukrainian forces are using drones to strike armored vehicles at their weak points to immobilize them, and targeting Russian trucks and even soldiers on foot, making it hard for Moscow to move men and supplies toward Ukrainian trenches.

Ukraine pioneered the use of drones on the battlefield early in the war, using store-bought quadcopters to spot Russian positions. But in the almost two years since, Moscow has made a huge investment in drones of all kinds, and is converting shopping malls in central Russia into drone factories, according to local activists.

Because of frequent Russian missile strikes, Ukrainian drone producers are keeping their operations smaller, with a few dozen employees in one building, a few dozen more in another, in hopes of keeping their work hidden.

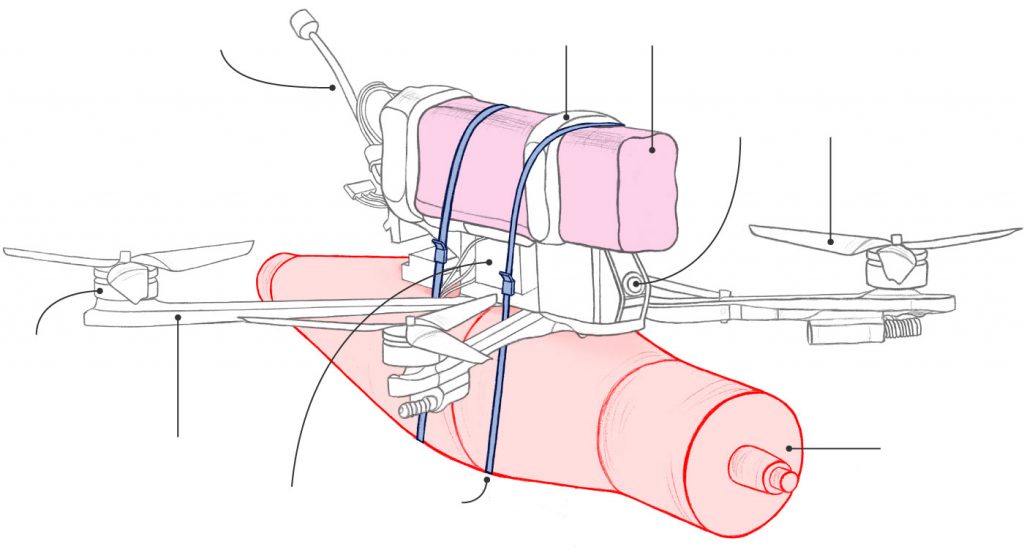

First Person View

FPV drones like this one, which can be manufactured for just a few hundred dollars each from parts mostly available on the commercial market, are becoming one of the most important weapons in Ukraine.

Note: Diagram is schematic

Source: Sparrow Avia

Jemal R. Brinson/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Still, they are aiming to produce on a mass scale. Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s minister of digital transformation, said the country is on pace to meet the goal President Volodymyr Zelensky set late last year of producing at least a million drones this year, an increase of more than 100 times from 2022. Ukraine now makes 62 different kinds of drones, and drone producers are working on new models that can fly farther, carry heavier munitions and evade Russian electronic jammers, which cut off contact between the drone and the pilot.

The Wall Street Journal visited one of Sparrow’s three facilities, which collectively make about 3,000 FPV drones a month. Havryluk and his partner invested roughly $500,000 to get the company off the ground, with the goal of eventually producing 10,000 drones a month.

Late last year, the company moved into an empty building in western Ukraine, installed some ventilation tubes, and turned it into an FPV factory.

The company purchases some parts—like carbon fiber, cameras and engines—but manufactures most parts and designs the drones in-house.

In one room, a 20-year-old engineer looked at models of the drones on screens, tweaking his design. Behind him, several 3-D printers cranked plastic parts.

In the next room, workers welded together battery packs, with different sizes for different drone models, then covered them in black plastic.

The drones themselves were assembled at the end of the hall.

Workers sat in pairs at desks, where they screwed, glued and welded parts together. The room was packed so tightly—with hundreds of drones in various states of assembly stacked around them on shelves and on the floor—that the employees risked knocking something over every time they stood up from their desk. There wasn’t yet a ventilation system in the room, and the welders covered their noses with scarves.

The finished drones look bare-bones compared with ones available online: a thin carbon-fiber body, with four sets of propellers and a battery pack strapped to the top.

“The biggest issue is getting parts from China, and the logistics of getting them here,” Havryluk said, noting that protests by truckers in Poland had slowed the flow of commercial goods into Ukraine in recent months. He said the company is spending roughly $14,000 on parts a month: “It sounds like a big sum, but for the army, it’s a small expense.”

The Ukrainian government buys about half the drones each month, Havryluk said. Volunteers and local governments buy up the rest and deliver them to military units.

Fedorov, the minister of digital transformation, said the government has offered a series of incentives for drone companies to scale up, including tax reductions and the elimination of import duties.

“The role of the state is more like coordination and creating opportunities,” he said, adding that the government was “offering big contracts for producers to scale up.”

So far, Sparrow has only 70 employees, all but three of them men. Havryluk said they planned to add 130 over the next two months. He hires only friends and relatives of current employees, wary of the danger each new staff member brings. If anyone betrays the factory’s location to the Russians, it will likely be targeted with missiles.

Havryluk said employees have an unofficial exemption from conscription, a significant perk when the Ukrainian military is planning to add up to 500,000 new soldiers.

“Not everyone can fight or wants to fight, but this is a way I can still be useful and help the army,” said Serhiy Khluhonets, a 35-year-old former construction worker who joined Sparrow two months ago and now works as a welder.

Out of each batch of 30 drones, one is taken for a test run at a nearby range. On a cold, cloudless January day, a test pilot slipped on the FPV goggles. He guided a 10-inch FPV drone off the snow into the air, and then zipped it back and forth above the tree line at 80 miles an hour.

Of the 11 models that Sparrow makes, its 7-inch drone (measured by the size of propellers it can use) is the most popular. Though it doesn’t fly as far and can only carry about 3 pounds of explosives, it is more maneuverable and, crucially, cheaper, said Andriy Vuhovskiy, head of Sparrow’s FPV department.

“While we’re defending and the Russians are assaulting, [soldiers] don’t need such a long range,” Vuhovskiy said.

Still, Ukraine is developing drones with longer and longer ranges, which its forces have used to strike oil refineries inside Russia this year.

Sparrow has developed a larger strike drone that can carry about 20 pounds of explosives. The company is also working on models that use artificial intelligence to hit the target, even if Russian electronic jammers cut off contact with the pilot.

“For now, the skills of the pilot are important,” Vuhovskiy said. “In the future, you won’t need as much skill.”

—Nikita Nikolaienko contributed to this article.

Write to Ian Lovett at ian.lovett@wsj.com