The New York Times is investigating itself.

Over the past several weeks, Charlotte Behrendt, a top Times editor in charge of probing workplace issues in the newsroom, has summoned close to 20 employees for interviews to determine whether staffers leaked confidential information related to Gaza war coverage to another media outlet.

It is the latest internal crisis at the Times, where management has been at odds with factions of the newsroom over union negotiations and coverage of sensitive topics like the transgender community and social justice.

Reporting about the Gaza war has been a particular flashpoint, especially over an in-depth article that found Hamas weaponized sexual violence in the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel. Some staffers questioned the reporting behind it and alleged that the suffering of Gazans isn’t getting the same attention. Times leaders in March said they stand by the reporting.

The internal probe was meant to find out who leaked information related to a planned podcast episode about that article. But its intensity and scope suggests the Times’s leadership, after years of fights with its workforce over a variety of issues involving journalistic integrity, is sending a signal: Enough.

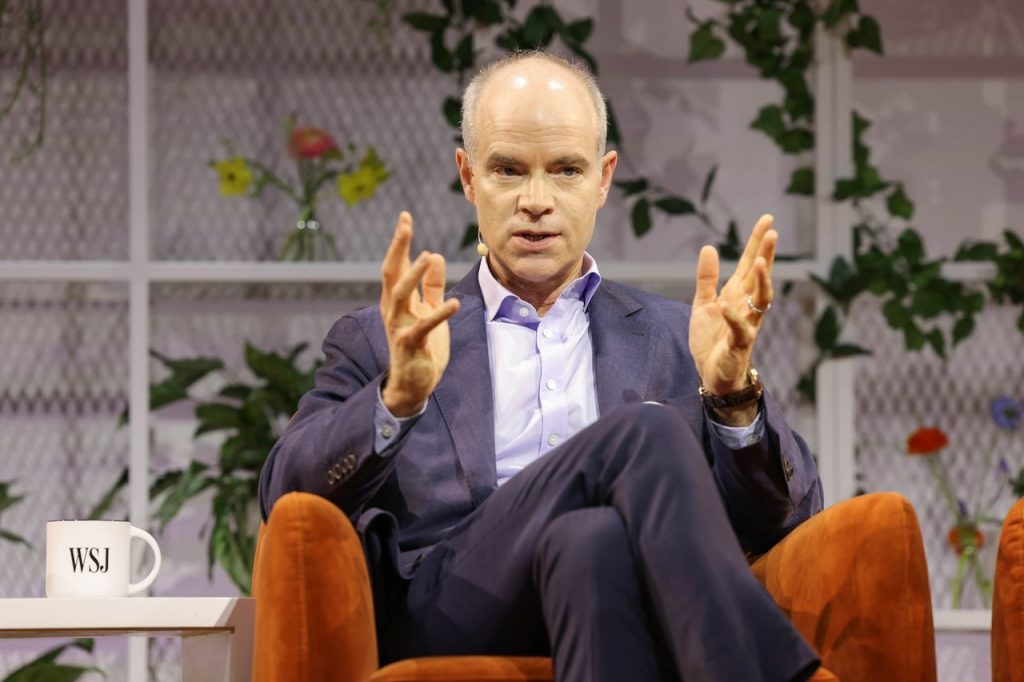

“The idea that someone dips into that process in the middle, and finds something that they considered might be interesting or damaging to the story under way, and then provides that to people outside, felt to me and my colleagues like a breakdown in the sort of trust and collaboration that’s necessary in the editorial process,” Executive Editor Joe Kahn said in an interview. “I haven’t seen that happen before.”

The Times is the envy of much of the news-publishing world, with more than 10 million paying subscribers and a growing portfolio of products like cooking and games apps. But while its business hums along, the Times’s culture has been under strain.

In many ways, it is a story familiar to companies big and small across America, as bosses struggle to integrate a new generation of workers with different expectations of how their jobs and personal lives should mesh—and whose evolving social values can sow discord in the workplace.

But these tensions have particular resonance at the Times, which has long prided itself as a standard-setter in American journalism. Newsroom leaders, concerned that some Times journalists are compromising their neutrality and applying ideological purity tests to coverage decisions, are seeking to draw a line.

Kahn noted that the organization has added a lot of digital-savvy workers who are skilled in areas like data analytics, design and product engineering but who weren’t trained in independent journalism. He also suggested that colleges aren’t preparing new hires to be tolerant of dissenting views.

“Young adults who are coming up through the education system are less accustomed to this sort of open debate, this sort of robust exchange of views around issues they feel strongly about than may have been the case in the past,” he said, adding that the onus is on the Times to instill values like independence in its employees.

Kahn said he welcomes the normal push and pull of any newsroom—journalists challenging each other’s assumptions and debating whether coverage is fair.

But he said opposition to the Hamas sexual-violence article, penned in late December by veteran correspondent Jeffrey Gettleman and two freelancers, crossed a line when confidential Times work-product was allegedly shared outside the newsroom.

Tensions have run high at the Times lately, especially over an in-depth article that found Hamas weaponized sexual violence in the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel. PHOTO: ANGELA OWENS/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Details about staffers’ pre-publication debates were revealed in an article published by nonprofit news organization the Intercept that said the podcast episode was shelved.

Some Times staffers said the probe was justified. But others said management is going too far. Behrendt, a lawyer by training whose official title is director of policy and internal investigations, asked for the names of participants in a chat group for Middle Eastern and North African Times employees and asked some staffers to name others who had discussed concerns about the Gettleman story, people familiar with the interview sessions said. At least one session lasted longer than an hour.

One staffer complained about the Gettleman piece in a letter to the Standards department, an official channel for raising internal concerns about the Times’ journalism. Behrendt, who had obtained the letter from another source, later called the author in for questioning. In the interview, she asked if anyone else helped her write the letter, and for her communications with a worker on the “Daily” podcast.

Stacy Cowley, a business reporter and Times union officer who sat in on a few interviews to represent staffers, said the Times is targeting employees who have been struggling to get the company to listen to their concerns about war-related coverage.

“Instead of taking them seriously, the company is turning around and bullying that group into silence,” she said. The union has filed a grievance alleging that the company was targeting a group of staffers of Arab and Middle Eastern descent. Times leaders said the allegations are false.

Strong passions

Coverage of the Israel-Hamas war has become particularly fraught at the Times, with some reporters saying the Times’s work is tilting in favor of Israel and others pushing back forcefully, say people familiar with the situation. That has led to dueling charges of bias and journalistic malpractice among reporters and editors, forcing management to referee disputes.

“Just like our readers at the moment, there are really really strong passions about that issue and not that much willingness to really explore the perspectives of people who are on the other side of that divide,” Kahn said, adding that it’s hard work for staffers “to put their commitment to the journalism often ahead of their own personal views.”

Joe Kahn, executive editor of the Times, acknowledged it can be hard for staffers ‘to put their commitment to the journalism often ahead of their own personal views.’ PHOTO: GARY HE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Last fall, Times staffers covering the war got into a heated dispute in a WhatsApp group chat over the publication’s reporting on Al-Shifa hospital in Gaza, which Israel alleged was a command-and-control center for Hamas.

As Israel advanced on the hospital, doctors there were disputing Israel’s claims that it was coordinating the evacuation of premature babies. When a Times reporter in the chat questioned whether information coming from the doctors could be trusted, another shot back: “Are you conflating every doctor at Shifa with Hamas?”

The first reporter called the response an “old trick” meant to attribute to a skeptic “some shade of racism or chauvinism” to “put him on the defensive.”

International editor Philip Pan later intervened, saying the WhatsApp thread—at its worst a “tense forum where the questions and comments can feel accusatory”—should be for sharing information, not for hosting debates, according to messages reviewed by the Journal.

“We need to do a better job communicating with each other as we report the news, so our discussions are more productive and our disagreements less distracting,” he wrote in the chat.

Some Times veterans said criticism of the publication’s work—from external sources or colleagues—can be healthy. “We should be open to criticism, think about what it means for our coverage, without allowing our independence to be compromised,” said Peter Baker, chief White House correspondent at the Times, in an interview. “Finding that happy middle space is a huge challenge, particularly in this era of polarization and social media and very loud discourse.”

The Times isn’t the only news organization where employees have become more vocal in complaints about coverage and workplace practices. War coverage has also fueled tensions at The Wall Street Journal, with some reporters in meetings and internal chat groups complaining that coverage is skewed—either favoring Israel or Palestinians.

At the Times, the intensity and sometimes-public nature of the sparring has forced management to intervene.

The company’s leaders in February deleted critical comments by Times staffers in the internal communication platform Slack about a trans-related opinion piece by Times opinion columnist Pamela Paul, for example, saying the company doesn’t allow criticism of colleagues or their work in large forums.

‘Trust team’

Despite the cultural turmoil, the Times’s business keeps growing. The company signed up 300,000 subscribers in the most recent quarter. A weak spot lately has been the online ad market, one reason shares in the Times are down 9% this year after rising 36% in 2023.

The publisher of the Times, 43-year-old A.G. Sulzberger , says readers’ trust is at risk, however. Some journalists, including at the Times, are criticizing journalistic traditions like impartiality, while embracing “a different model of journalism, one guided by personal perspective and animated by personal conviction,” Sulzberger wrote in a 12,000-word essay last year in Columbia Journalism Review.

Sulzberger greenlighted a “trust team,” a group focused on efforts to improve reader confidence in its reporting. The group is behind features such as disclosures that explain why the Times uses anonymous sources and videos of reporters discussing their work.

Despite such moves, NewsGuard, an organization that rates credibility of news sites, in February reduced the Times’s score from the maximum of 100 to 87.5, saying it doesn’t have a clear enough delineation between news and opinion. “Our standards and processes are among the most robust and rigorous of any news organization in the country,” said a Times spokeswoman. “Nothing has changed in how we label our news and opinion coverage.”

Seed of activism

The current dynamics at the Times stretch back to 2020, when a seed of employee activism took root in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing. In June of that year, the staff staged a rebellion after the publication of an op-ed piece by Republican senator Tom Cotton, “Send In The Troops,” that suggested the U.S. military should quell riots. Some staffers said it made them feel unsafe.

Within days the Times had parted ways with Editorial Page Editor James Bennet . In a recent account of those events in the Economist, Bennet said Sulzberger supported the decision to publish it, and said he was forced to resign. Sulzberger has said he disputes Bennet’s narrative.

The company said it conducted a review after publishing the op-ed and found “the piece itself and the series of decisions that led to its publication did not hold up to scrutiny,” said a Times spokeswoman.

Emboldened by their show of strength on Bennet, employees would flex their muscles again on multiple occasions, pushing to oust colleagues they felt had engaged in journalistic or workplace misconduct.

In 2019, Donald G. McNeil Jr., a star science and health reporter, was investigated internally over allegations he had used racist language during a Times-sponsored trip to Peru for high-school students. Two years later, in a Medium post recalling the events, McNeil said he repeated the N-word while speaking to a student about a classmate’s use of the slur. Then-editor Dean Baquet told the staff that while McNeil “showed extremely poor judgment” he was given a second chance because “it did not appear to me that his intentions were hateful or malicious.” After 150 staffers protested, the Times and McNeil ultimately parted ways .

“Donald was reprimanded in 2019 and his eventual departure involved more than one issue,” said a Times spokeswoman.

Employees were making their voice felt at the Times. At the same time, some editors and reporters were growing concerned that some Times journalists were letting their personal views dictate which stories to pursue—or not pursue.

One way to counter that trend was with the creation of a new beat for reporter Michael Powell to cover issues around free speech and expression. Powell created the beat in coordination with then-Deputy Managing Editor Carolyn Ryan, who had been tasked with safeguarding independence in the newsroom.

One thing Powell noticed, he said, was that coverage that challenged popular political and cultural beliefs was being neglected. Powell’s work includes a story on MIT’s canceling of a lecture by an academic who had criticized affirmative action , and another examining whether the ACLU is more willing to defend the First Amendment rights of progressives than far-right groups.

“We kind of both had a nagging sense that we needed to write in a much more systematic way about these third-rail issues, of identity, gender, speech,” said Powell of his early conversations with Ryan. “The fact that I had all this territory was not a good sign.”

Kahn says it isn’t up to only one reporter to do this kind of work. “It’s a commitment that only makes sense across all the beats in the newsroom,” he said.

Powell left last year to join the Atlantic, and the Times recently appointed Jeremy Peters, who had been covering media politics, to the role.

Drawing a line

Management concerns about independence deepened in February of last year when some Times contributors and staff signed an open letter to the Times’s standards editor laying out complaints about transgender coverage.

The letter, signed by over 1,000 Times contributors, including a small number of full-time staffers, criticized the characterization of trans people in the article, “The Battle Over Gender Therapy,” and the framing of the article “When Students Change Gender Identity, and Parents Don’t Know .”

That same day, Glaad, a nonprofit LGBTQ advocacy organization, sent a similar letter protesting the coverage.

Kahn, who succeeded Baquet as executive editor in June 2022, and Opinion Editor Kathleen Kingsbury said in a letter to staff that they wouldn’t tolerate participation by Times journalists in protests or attacks on colleagues.

Jazmine Hughes, a New York Times Magazine writer, who had signed the trans coverage petition and was warned not to do it again, left months later after signing another petition from the activist organization Writers Against the War on Gaza. Hughes resigned “under pressure,” she said in a statement at the time in a union newsletter.

Jake Silverstein, editor-in-chief of the Times’ magazine, described her actions as a “clear violation of The Times’s policy on public protest.”

Divisions have formed in the newsroom over the role of the union that represents Times staffers, the NewsGuild-CWA. Some staffers say it has inappropriately inserted itself into debates with management, including over coverage of the trans community and the war.

While the Guild represents staffers across many major U.S. news outlets, its members also include employees from non-news advocacy organizations such as pro-Palestinian group Jewish Voice For Peace, Democratic Socialists of America and divisions of the ACLU.

When Times staffers logged on to a union virtual meeting last fall to discuss whether to call for a cease-fire in Gaza, some attendees from other organizations had virtual backgrounds displaying Palestinian flags. The meeting, where a variety of members were given around two minutes to share their views on the matter, felt like the kind of rally the Times’ policy prohibits, according to attendees.

Partly in response to such activities, some Times journalists launched an “Independence Caucus” for journalists at the Times and other outlets.

Political project

When it comes to coverage of U.S. politics, the Times has sought to counter the perception that it has a liberal bias. After Donald Trump won the presidency, reporters from the national desk were sent to places where Trump proved popular, like Pittsburgh, Fort Smith, Ark., and eastern Iowa. The Times also held question-and-answer sessions with residents in some of those areas.

The remit was to do deep dives reflecting the points of views of people around the country on topics like immigration and trade, said Trip Gabriel, a reporter on the national desk at the time.

“We were looking to better understand voters or Americans we may have overlooked but also to convince readers we were interested in those peoples’ points of views and people should read the Times in those places,” said Gabriel, who’s currently writing obituaries for the Times.

Kahn said the Times’ national desk now is bigger and more equipped to cover an unprecedented election. The Times will also be more committed to covering misinformation in the 2024 election, with a team of eight to nine people, he said.

In January, Sulzberger shared his thoughts on covering Trump during a visit to the Washington bureau. It was imperative to keep Trump coverage emotion-free, he told staffers, according to people who attended. He referenced the Times story, “Why a Second Trump Presidency May Be More Radical Than His First,” by Charlie Savage, Jonathan Swan and Maggie Haberman, as a good example of fact-based and fair coverage.

Kahn defended the focus the Times, like other outlets, has given to President Biden’s age, despite some concerns from staffers and outsiders.

“What you do is you pursue every story, you follow the facts and you give readers the information they need to make intelligent decisions,” he said.

Write to Alexandra Bruell at alexandra.bruell@wsj.com