PARIS—French solar-panel company Photowatt once powered Europe’s ambition to become a renewables manufacturing giant, one that would provide the technology to help achieve the continent’s far-reaching climate goals.

Today, Photowatt is instead hanging by a thread, a potent symbol of the West’s struggles to fend off fierce competition from China .

A wave of cheap Chinese exports now threatens millions of jobs and is stirring fresh friction between Beijing and leaders in the U.S. and Europe. Photowatt’s fate, and the decimation of Europe’s solar-panel industry, is a warning to the U.S. , which is now considering how to protect American industries from renewed pressure from China .

Photowatt’s orders have plunged, its customers lured away by solar panels imported from China at rock-bottom prices. Cash infusions from the French government keep it alive. Even Photowatt’s state-controlled owner, the power company EDF, has largely stopped buying its panels in favor of those made by Chinese companies.

“There are fewer and fewer of us. We lose skills, workshops close—it’s hopeless even,” said Emilie Brechbuhl, an engineer and union delegate at Photowatt. “We aren’t competitors of the Chinese. We are nonexistent.”

Beijing is seeking to stimulate a flagging economy by channeling investment into its vast manufacturing sector. That threatens a repeat of the so-called China shock two decades ago when Chinese exports flooded global markets and destroyed many Western competitors.

In particular, fears are surging across the West that China will crush its green industries, forcing the U.S. and Europe to rely on a geopolitical rival in China for the goods that are expected to power the low-carbon economy of the future.

In particular, fears are surging across the West that China will crush its green industries, forcing the U.S. and Europe to rely on a geopolitical rival in China for the goods that are expected to power the low-carbon economy of the future.

The sectors that Chinese officials dub the “new trio”—solar panels, electric vehicles and batteries—are creating massive overcapacity, according to Western governments. China’s wind-turbine manufacturers are also hunting for customers in the West, threatening an industry still led by European and U.S. companies like Vestas and GE Vernova.

During a visit to China this month, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen pressed Beijing to rein in subsidies for green manufacturers. Yellen said the Biden administration was determined to prevent a repeat of the wave of China imports 15 years ago that drove U.S. solar panel producers and other manufacturers out of business.

“It would not be acceptable to the United States, to President Biden, that this happen again,” she said.

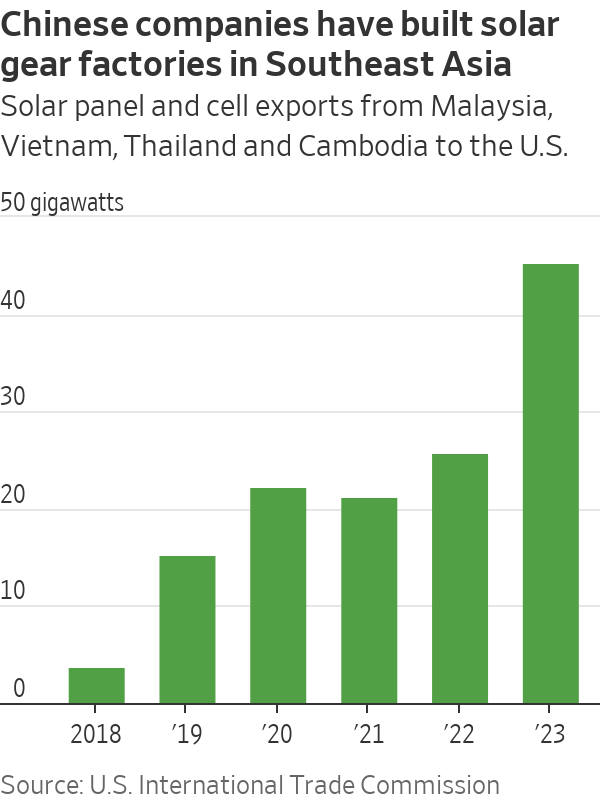

The U.S. has imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels for more than a decade. That has slowed imports directly from China. But Chinese companies have set up factories in Southeast Asia that are exporting heavily to the U.S.

In Europe, the alarm is so great that authorities are abandoning some of their long-held reluctance to challenge Beijing.

Over the past two months, they have opened probes into subsidies potentially channeled from Beijing to Chinese solar-panel companies in Romania and wind-turbine companies in France, Spain, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria.

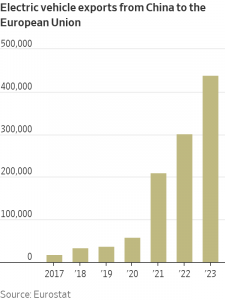

The investigations follow a probe into Chinese electric-vehicle subsidies that is likely to result in import tariffs in the coming months. Allowing China to grab most of the European EV market as it did solar panels would be disastrous for the continent’s economy, where millions of people work in the auto industry.

Europe’s EV companies are competing against made-in-China models that are usually 20% to 40% cheaper. For example, the MG4, a hatchback made by China’s SAIC Motor , sells in France starting around €25,000—the equivalent of $26,700—compared with €39,000 for the Volkswagen ID.3 hatchback.

Europe’s EV companies are competing against made-in-China models that are usually 20% to 40% cheaper. For example, the MG4, a hatchback made by China’s SAIC Motor , sells in France starting around €25,000—the equivalent of $26,700—compared with €39,000 for the Volkswagen ID.3 hatchback.

“We can’t afford to see what happened on solar panels happening again on electric vehicles, wind,” Margrethe Vestager , the European Union’s competition commissioner, said this month.

Chinese officials have rejected criticisms of Beijing’s industrial policy and accused the West of hypocrisy. Last month, China filed a complaint at the World Trade Organization against U.S. tax credits that are reserved for domestic manufacturers of electric vehicles.

While Europe has already faced a surge of electric-vehicle imports, the U.S. hasn’t been hit yet—partly because it has already placed tariffs on all Chinese cars. But the Chinese EV giant BYD is planning to build a plant in Mexico . That would allow it to export with minimal tariffs to the U.S. BYD has said it doesn’t plan to enter the U.S. market.

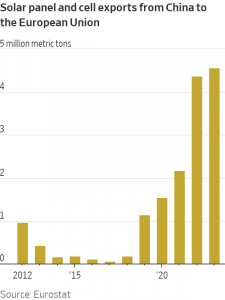

China’s green-energy equipment exports pose a dilemma for the West. Its cheap yet high-performing solar panels, EVs and batteries are accelerating the global shift to clean energy by making it more affordable. Europe is counting on solar panels to be its leading source of electricity by 2030 and will need to install hundreds of millions of panels by then. The continent’s imports of solar panels from China have more than quadrupled over the past decade. China now controls more than 95% of the European market.

Most EU governments oppose import tariffs on Chinese panels. Instead, they pledged this month to give European panel producers a leg up in tenders for publicly subsidized solar farms and use government funds to support the industry. Help hasn’t arrived in time for a number of EU producers that shut in recent months after a huge influx of Chinese panels over the past year.

When the U.S. slapped steep tariffs on Chinese solar panels in 2012, Europe was preparing to do the same. But then China retaliated, announcing an antidumping probe on French wine and signaling it was considering a similar move against European luxury cars, a pressure point for Germany due to its large car sector.

The EU set a minimum import price on Chinese panels. Much of the European solar business died off in the following years. The EU scrapped the minimum price altogether in 2018.

“China is very good at playing the member states like a piano,” said the former EU trade chief Karel De Gucht .

Photowatt survived thanks to the French government’s determination to keep it afloat. In 2012, then-President Nicolas Sarkozy visited its factory near Lyon to announce that he had ordered EDF to buy the company. It was on the verge of bankruptcy. EDF’s renewable-energy arm would buy all the solar panels produced by Photowatt for its own solar-power installations, Sarkozy said.

“Photowatt is a symbol,” Sarkozy said. “We don’t want the only jobs created by the solar supply chain in France to be in the installation of panels.”

Photowatt makes silicon wafers that are then assembled into solar cells and panels, one of the few companies outside China in that part of the supply chain. Photowatt invested in a wafer technology that was supposed to allow it to compete against the Chinese. The production process was less energy-intensive than the Chinese technology—and thus more environmentally friendly—but the wafers were less efficient.

The bet didn’t work out: Developers want panels with the maximum output at the lowest cost.

As Photowatt continued to lose tens of millions of euros a year, EDF slashed purchases of its panels and sought to shut the company down. But the government of President Emmanuel Macron nixed that idea.

“EDF wanted to close Photowatt,” Jean Castex said in 2021 when he was the French prime minister. “We stopped them!”

These days, EDF says it doesn’t want to make solar panels and is trying to find an “industrial partner” for Photowatt. Macron’s government this month announced financial incentives for solar-panel production in France. Two large factories are in the works but neither has broken ground yet.

“We have managed to free ourselves from dependence on Russian gas and oil. Do we want to move to a dependence on Chinese photovoltaic panels?” said French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire . “We must therefore produce solar panels on our territory.”

Write to Matthew Dalton at Matthew.Dalton@wsj.com