Swiping through Tinder in Saudi Arabia, a profile of a woman in her mid-20s includes photos of her manicured hands holding flowers, a matcha latte, a tennis court and some art. She reveals no photos of herself.

“Looking for a partner who can play sports,” her biography reads. “And if you are looking for a fun and short relationship, swipe left.”

Another profile of a woman in her early 20s obscures her face with emojis or her phone blocking view. She features photos from her point of view—reading in a cafe, driving with a puppy in her lap, traveling around Istanbul. One man shares images with his face showing, wearing a thobe and headdress while holding a falcon on his arm, with other photos at the gym and pool. Another man includes only a hook emoji in his bio—a signal that he is looking for a hookup.

It may seem like an unusually covert way to date in the eyes of many Americans. But young Saudis are navigating a burgeoning world of romance, as the country’s loosening of strict moral codes gives way to a dating culture in bloom. Look no further than the millions of people who downloaded Tinder in Saudi Arabia over the past five years to understand how much the Islamic kingdom has relaxed its customs around courtship.

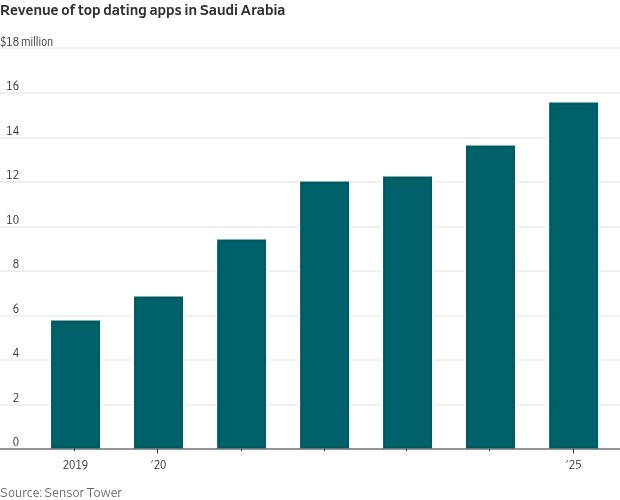

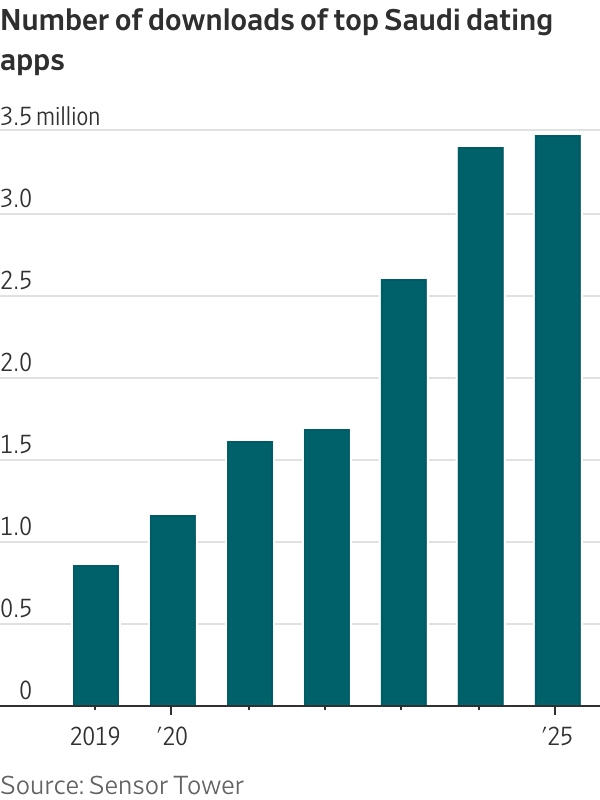

It is a significant change from the days when most meetings between young people were carefully managed by relatives with an eye to marriage, and any form of premarital romantic relations was off limits. The top matchmaking apps in Saudi Arabia brought in nearly $16 million in net in-app revenue, according to Sensor Tower, a market-intelligence firm. Downloads of the top dating apps in the country of around 35 million people have risen every year for half a decade, hitting 3.5 million in 2025.

Some young people are now being more overt on their dating profiles, revealing their faces and personal details including names, interests and universities attended. Some post photos of themselves in traditional Saudi dress: for men a thobe and headdress, for women an abaya and headscarf.

It is becoming more common in some places to see mingling between men and women who aren’t relatives, socializing that was anomalous a decade ago. Young Saudis, including one attending a desert rave held in the middle of the night in the neighboring United Arab Emirates, said their generation was still fumbling around to figure out how to manage more casual interactions or find spouses outside the purview of parents.

“My generation in Saudi grew up secluded and in gender-segregated schools,” said Tala Alarfaj, a 23-year-old from Saudi Arabia’s East Coast. “People are still getting used to the concept of dating.”

While secret dating has long been a reality, the cost of getting caught by agents from Saudi Arabia’s religious police, who once but no longer frequently roamed the streets, turned young lovers away. Parents tended to arrange marriages through family connections, and although the culture has loosened up in the past decade, Saudi society remains conservative when it comes to gender-mixing, dating and sex.

Now, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, is nearly a decade into an ambitious modernizing project. His massive social and economic development plan, called Vision 2030, aims to brighten Saudi Arabia’s global image, woo international tourists and high-skilled expatriates from the West and wean the kingdom off its reliance on petrodollars. Since his appointment in 2017, Saudi Arabia has reined in its religious police, lifted a ban on women driving, allowed restaurants and cafes to desegregate by gender and promoted cinema and music events. In recent months, the kingdom has quietly loosened long-enforced restrictions of alcohol.

Religious police once cracked down on the sale of love-themed items on Valentine’s Day, including red roses and gifts meant for the celebration, which is named after a Christian saint. Now, those items are freely exchanged between lovers, and luxury hotels are promoting romantic packages for the holiday.

The social changes have led to Saudis wooing one another at hip cafes in more liberal cities like Riyadh and Jeddah. They are getting to know each other online and at large events including Riyadh Season, an annual entertainment festival. Places to openly date are still limited, and unmarried lovers huddle in discreet, permissive cafes they find through word of mouth, while others in more conservative circles have secret dates in cars with tinted windows.

Women and gay users in the country feel the most stigma around dating, often obscuring their faces and leaving few identifying details on dating apps. Some post no photos of themselves at all. Instead there are pictures of cats, fast cars, landscapes or fancy meals. Saudis in gay relationships said they got away with public dates, as two people of the same sex hanging out raises few suspicions. They, too, are using dating apps, subtly hinting at their sexual orientation by including their preferred pronouns in their bios and opening up their profiles to be viewed by the same sex.

Some young Saudis say they still feel shame around dating even as it becomes more ubiquitous. Men are sometimes reluctant to marry a woman they’ve met on the dating scene because of the stigma.

“When you’re secluded for way too long, you don’t know the steps, you don’t know how to properly get to know the other gender when it comes to dating,” Alarfaj said. “We are just now figuring all that out.”

Saudi Arabia’s Sharia-based justice system continues to prohibit sex outside marriage and homosexuality. While the kingdom appears to have eased up on prosecution and punishment, judges could still sentence people to flogging, imprisonment and even death for consensual sexual relations the state considers illegitimate, according to rights groups.

“These social changes exist in a legal gray area,” said Andrew Leber, an assistant professor at Tulane University and a nonresident fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Middle East program. “The scope of what is tolerated is much greater than what is legally guaranteed.”

Some religious Saudis and members of the kingdom’s diminished but still influential clerical class are concerned the crown prince is taking things too far. They don’t want Saudi Arabia, which occupies a sensitive position as a guardian of Islam’s holiest sites, to end up like the United Arab Emirates, where alcohol flows freely, prostitution operates indiscreetly and legal gambling is on its way.

“A top-down shifting from something quite restrictive is complex,” said Philippe Thalmann, a Cambridge University anthropology researcher focused on social reform in Saudi Arabia. “But the apps are surely part of that transition.”

Alarfaj said some conservative families have become more strict, taking up the slack as the state backs off of its enforcement of social restrictions.

“The changes are happening so fast, and some people are afraid of it,” she said.