Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fleeing Israeli strikes have tripled the population of Rafah, turning this small southern Gaza city on the Egyptian border into a flashpoint in one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

Families displaced from points north by Israel’s war against Hamas have packed schools and other shelters beyond capacity, and pushed rents for small apartments from $100 before the war up to nearly $5,000. New arrivals in Rafah have few options beyond camping in parks and empty lots, using salvaged materials for shelter or sleeping in the elements as winter sets in. The United Nations warns that Rafah could soon host half of the Gaza Strip’s roughly 2.2 million people.

Aid groups have already documented outbreaks of disease, including hepatitis, rabies and herpes, resulting from overcrowding, inadequate water and overextended sewage-treatment plants. A fuel shortage prevents desalination plants from fully treating water, causing widespread diarrhea.

People are chopping down trees for firewood or scavenging it from bombed out houses to cook and boil drinking water. Prices for food and bottled water are surging, while supplies of medicine and sanitary products like diapers and tampons dwindle.

Boys hold containers while they line up, as displaced Palestinians, who fled their houses due to Israeli strikes, shelter in a tent camp near the border with Egypt, amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinian Islamist group Hamas, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip, December 11, 2023. REUTERS/Mohammed Salem

“Everywhere there are families in the streets, because they have nowhere else to stay,” said Mustafa Ayad, who fled Gaza City earlier in the war with 13 family members.

Ayad’s family first took refuge in Khan Younis, south of Gaza City, before fleeing again last weekend following a night of shelling by Israeli tanks targeting Hamas militants a few hundred feet away. They made the five-mile journey to Rafah, where they were squatting in the center island of a busy traffic circle, under a mockup of a rocket named after Hamas’s armed wing.

“I don’t know what to do,” he said. “It’s a total mess, it’s unimaginable.”

Israel launched a military campaign aimed at destroying Hamas, a U.S. designated terrorist group, in response to the militants’ Oct. 7 attack, which killed an estimated 1,200 people and took some 240 hostages back to Gaza. At least 137 hostages, including 19 dead bodies, are still being held inside Gaza, according to the Israeli prime minister’s office, after Hamas freed more than 100 captives in exchange for the release of Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli prisons.

Israel resumed its bombing and ground operations after talks to extend a weeklong truce in late November collapsed over disagreement about which hostages would be released. Under the terms initially agreed by the two sides, Hamas had to release all the civilian women and children first, but failed to do so, mediators said.

Displaced people began trickling into Rafah within the first week of the war.

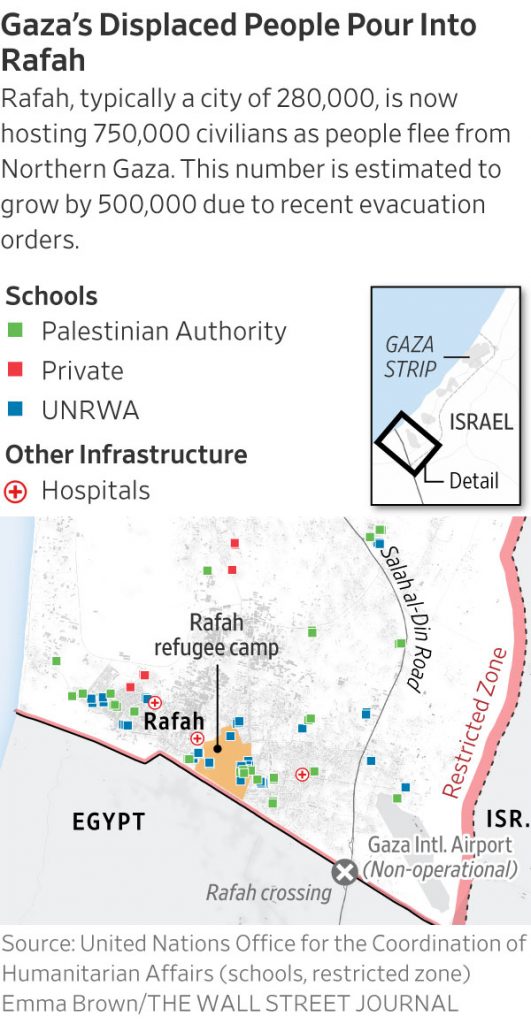

Rafah, an ancient city that dates back to the Bronze Age, straddles the Egyptian frontier and contains the Gaza Strip’s only border crossing that doesn’t lead into Israel. As fighting to the north progressed, more civilians moved south. Rafah was spared the most intense bombing, but still saw near-daily airstrikes. A few thousand people—mostly foreigners and dual nationals—have been allowed to leave for Egypt through the Rafah crossing.

By the time the warring sides agreed to a pause in hostilities last month, around 1 million people were already displaced to southern areas, including Rafah. When fighting resumed on Dec. 1, Israeli forces began focusing on southern Gaza, primarily Khan Younis. In phone calls and leaflets dropped from the sky, they warned civilians to leave the battle zone there. Many are ending up in Rafah, where renewed Israeli airstrikes have killed at least 68 people in the past week, according to the United Nations.

Rafah is already hosting 470,000 displaced people alongside its existing population of some 280,000. The latest evacuation orders could displace half a million more people to Rafah, according to Thomas White, director of affairs in Gaza for the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees.

“The water and sanitation infrastructure…will not even come close to providing for an IDP population that could reach a million people,” White said on X.

Palestinian children hold pots as they queue to receive food cooked by a charity kitchen, amid shortages in food supplies, as the conflict between Israel and Hamas continues, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip December 14, 2023. REUTERS/Saleh Salem

For the Israeli military, the battle for the southern Gaza Strip is expected to be even more complex and difficult than in the north. Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups are expected to make a stand there as Israeli evacuation orders push much of the local population into a smaller patch of territory.

Asked if Rafah could become a target, the Israeli military said it doesn’t comment on future plans.

Israel says its military is targeting Hamas and that it has made extensive efforts to ensure the safety of civilians, including using leaflets, text messages and other means to warn civilians of impending warfare and direct them to designated safe zones in Gaza. More than 17,000 Gazans, a majority women and children, have been killed in the past two months, according to officials in the Hamas-ruled enclave. The figure doesn’t distinguish between militants and civilians.

The humanitarian crisis could also have broader ramifications, if Palestinians crowded in Rafah try to force their way into Egypt, which has so far resisted large-scale displacement out of concern that it would spread instability and spell the end of any future Palestinian state. The Egyptian army may then face a choice between using force to push back unarmed civilians or accepting a refugee crisis in the already precarious Sinai Peninsula.

“What Israel is offering the Palestinians boils down to two things: you either flee—go anywhere except Gaza and Israel—or die in Gaza,” said Mohannad Sabry, a scholar at King’s College London’s Defense Studies Department and the author of a book on Sinai.

A reprise of 2008, when Hamas militants destroyed part of the Egyptian border wall with an explosion and around half of Gaza’s population crossed in for nearly a week, is “becoming more and more probable,” said Sabry. “What do you expect from people who are sitting there with hellfire raining on them from the sky? Israel is forcing the situation in that direction.”

An aerial view of tent camps where displaced Palestinians, who fled their houses due to Israeli strikes amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinian Islamist group Hamas, shelter in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip December 9, 2023. REUTERS/Mustafa Thraya TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

A decade ago, Egypt faced a wave of insurgency in Sinai and the army razed its side of Rafah, relocating thousands of inhabitants and expanding the buffer zone with Israel, where it dug a ditch 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep. Now, Egypt is preparing for the possibility that the border won’t hold, building sand berms on its side of the border.

That may not be enough. Many in Gaza fear that once enough people gather in Rafah, Israel will bomb the border to encourage them to flee into Sinai. An Israeli military spokesman declined to comment on such scenarios.

After walking most of the way to Rafah with more than 30 relatives following intense shelling in Khan Younis on Monday night, Mahmoud Al-Kudhair said there’s no way he will carry on to Sinai. “We prefer to die here,” he said. Another evacuee, 30-year-old Younis Nasr, said if Sinai becomes an option, he might consider it “for the sake of the children.”

For now, the streets of Rafah are teeming with people in search of basic items like flour, salt, sugar and canned goods. A few fruit stands keep operating, but most shops closed after depleting their stocks amid an Israeli blockade of the enclave. Children beg for handouts.

“We are tossed in the street. Where shall we go?” said Mahmoud Shushaa, who was sitting on a donkey cart in a busy Rafah roundabout on Monday, surrounded by children. “We came from Khan Younis, and they asked us to go to Rafah, but we didn’t find a proper place. We went to the schools, but the schools are full.”

The Fatema al-Khateeb school in Rafah’s Al Shaboorah district has the capacity to shelter 1,500 people. As displacement in Gaza increased, its director said he pushed that to 4,000 and then again to 6,000, at which point the school could no longer provide everyone a meal a day. It began distributing partial portions to try to get everyone at least 1,000 calories a day, even as new arrivals camped outside the gates.

Tal al-Sultan, an existing refugee camp on the edge of Rafah, is where the Israeli military has specifically urged people in Khan Younis to move. In an empty lot surrounded by low-rise residential buildings, a few hundred people erected makeshift shelters out of wooden two-by-fours and nylon tarps. Unrwa has distributed hundreds of tents in Rafah, but most people have to make their own.

On Sunday, 72-year-old Ibrahim Abdullah crouched on his knees, digging a hole in the sand with his hands to place posts for a tent. Originally from Gaza City, he and his family have relocated four times since the war began, ending up in Rafah.

“God willing it will be safe,” he said. “We hope they are telling the truth.”

-Ghassan Adnan, Saleh al-Batati, Suha Ma’ayeh and Abeer Ayyoub contributed to this article.