For years, the Lauder family hosted the annual meeting for shareholders of their cosmetics giant at the elegant Essex House overlooking the southern edge of New York’s Central Park.

In a scene that looked more like a wedding than a corporate meeting, attendees would nibble on gourmet pastries and tropical fruit and leave with goody bags filled with face-cream samples, perfumes and lipsticks.

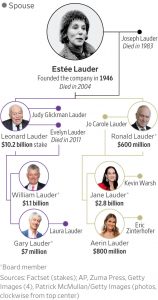

In between, they would mingle with the legendary New York clan that has controlled Estée Lauder since its founder first put her creams in jars more than 70 years ago: her son Leonard, who secured the brand’s place in America’s department stores; his brother Ronald, who ran for mayor of New York and became an art connoisseur; Ronald’s daughter Jane, a marketing executive with stints leading Origins and Clinique; and her cousin William, who helmed the company from 2004 to 2009.

This year, instead of going to a luxury hotel, shareholders logged into a virtual 34-minute meeting, a Covid carry-over. And behind the screens, a family skirmish over the struggling business and its future is roiling the empire just as Leonard, aged 90, officially ends his term as a board member.

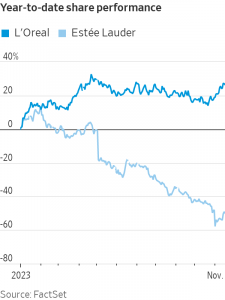

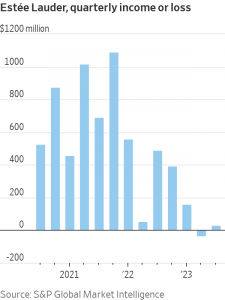

Estée Lauder shares have plunged about 50% this year, erasing roughly $45 billion in market value. Its China business has become a drag on profits. Some of its brands have been slow to tap into TikTok to reach younger consumers. Competitors are faring better, such as French giant L’Oréal, whose shares are up nearly 30% this year, or luxury conglomerate LVMH, which owns Sephora and is behind brands such as Dior fragrances and Fenty Beauty.

The founding family and board are divided about what to do—a state of disagreement the Lauders prefer to keep out of public view. Leonard and other members of the board are dissatisfied with Estée Lauder’s current chief executive, Fabrizio Freda, according to people familiar with the matter. Leonard’s 63-year-old son William, who is executive chairman, and other directors still want Freda at the helm to execute a turnaround plan he’s set in motion to clear out unsold inventory and boost profits. Jane, age 50, an heir from the other side of the family, is on the shortlist of internal CEO contenders, some of the people said.

Some board members are considering external candidates in addition to internal ones to succeed Freda; former board member Irv Hockaday is advising Estée Lauder on CEO succession, people familiar with the matter said. Some family members and other directors have informally raised questions over whether the next CEO should be an expert in business turnarounds or in building brands and employee morale.

In written statements, the Estée Lauder board and the family said they support the current CEO. Freda, 66, declined to comment through a spokeswoman.

“The Board of Directors has confidence in Fabrizio and strongly supports his profit recovery plan,” Charlene Barshefsky, a longtime member of the Estée Lauder board and its lead independent director, said in a statement. “The company is taking the necessary measures to address near-term performance and drive future growth.”

“Together, we have a deep commitment to, passion for and responsibility to the legacy and the future of this company,” William Lauder said on behalf of the family.

His father, Leonard, added: “I am confident The Estée Lauder Companies is in good hands. We have the best brands and the best people, and William and Fabrizio’s skillful and thoughtful management will take us into the future.”

The Lauder family, which collectively has seen its fortune shrink by around $15 billion this year, is an iconic example of the American dream. They are a close group of parents, children, uncles, aunts and cousins—inspired by a matriarch—that has worked from the ground up to build a commercial dynasty, but who also have had time to socialize their way to the top of New York society with philanthropic and artistic patronage.

The company’s namesake was one of the country’s most famous women entrepreneurs. Estée Lauder, born Josephine Esther Mentzer in 1908, learned how to make skin creams from her uncle in the kitchen, and started selling them in the 1930s and 1940s, pioneering the idea of free samples. She would give women facials in the Miami hotel where she and her family sometimes stayed, her elder son, Leonard, said in 2021.

Estée brought Leonard into the business from a young age. She took him on sales calls at salons. She took him to dinner with the company accountant and lawyer in 1946 on the night she decided to launch Estée Lauder Cosmetics as a formal entity. He was just a teen.

For the Lauders, work was family, and family was work, and work and family mean everything. When asked if Leonard resented his mother always working, he said in 2021: “Not at all. Work was love.”

Later, Leonard’s wife, Evelyn, held many titles at Estée Lauder, including director of new products and marketing. They worked together—and sometimes stole a kiss at the office—during their five-decade marriage.

The dynamics of familial attachment at work and beyond the office remain strong today, in the third generation away from Estée’s kitchen-cream chemistry. Aerin, Ronald’s daughter, wrote an Instagram post on Aug. 31: “#throwbackthursday NYC night out with my uncle Leonard. His famous blue notes have become collectors’ items. He forever reinforces brand equity and excellence. Recently, he told me he liked to take employees to the archives and serve donut holes and coffee and tell stories about the various brands. Thank you LAL (Leonard A. Lauder) for your constant passion and advice.”

The night out was, of course, black tie. The Lauders have exercised their wealth as benefactors of New York’s cultural institutions and have often been photographed over the years at fundraising galas. Leonard and Ronald are both serious art collectors and some of the art is displayed at the company’s offices. In 2013, Leonard donated $1 billion of cubist artwork to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Whitney Museum of American Art is now housed in a building named after him, its former chairman.

Ronald has been a fierce advocate for returning art stolen by the Nazis to its original owners. He was ambassador to Austria under Ronald Reagan and is a co-founder of the Neue Galerie of German and Austrian art on the Upper East Side of New York. Ronald in 2006 famously purchased Gustav Klimt’s 1907 painting of a Jewish socialite, “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer,” for $135 million — at the time the largest sum ever paid for a painting.

The blue notes Aerin referred to on Instagram are written words of encouragement and praise Leonard would scribe to colleagues or employees on notepads the color of Estée Lauder’s signature blue.

Aerin’s father Ronald worked in the family business and had various stints on the board, but never served as the company’s CEO. The last time Estée Lauder changed CEOs, he said he wasn’t sure that he wanted his younger daughter Jane, then a 34-year-old executive in the family’s business, to serve in that spot. “I don’t know if I’d wish it on her,” Ronald said in 2008.

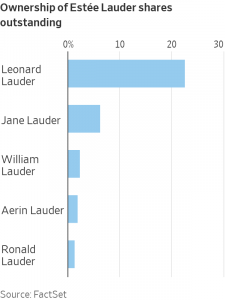

Getting the Lauder family on the same page about succession is essential, given that its members still hold an ownership stake of nearly 35%, including supervoting shares that collectively give them control over more than 80% of the voting power. There is also an agreement that Leonard and his brother, Ronald, each get to fill two seats on the board, which currently has 15 members. Leonard may continue to attend board meetings as chairman emeritus, and his younger son, Gary, is joining the board.

In the 1970s, Estée handed over the top job to Leonard, and she stayed involved until her death in 2004. Leonard expanded the business, added brands like MAC and Aveda, and took the company public in 1995—a milestone the family was photographed celebrating together with Champagne. William took over as CEO in 2004, before the company brought on Freda, an outsider, to run the business.

The Italian-born executive spent more than two decades at Procter & Gamble rising the ranks to run its snacks business before the Lauders recruited him. Freda has run the company for about 15 years, and is the first CEO who didn’t come from the family or rise up through the company.

The stock’s decline this year has heightened tensions between Leonard and William, who has worked the most closely with Freda and remains the current CEO’s biggest patron. In May, William wrote a memo to staff expressing the board’s support for Freda’s continued leadership. In board meetings, Freda and William typically sit at the head of the table.

The father-and-son friction isn’t entirely unfamiliar, as some of the company’s drama is typical generation-gap fare. William would sometimes complain his father was acting like his grandmother Estée did with Leonard in trying to maintain the status quo rather than evolve. “My father is a master at laughing at himself. And I’m very, very good at calling him on his stuff,” William told Town & Country magazine in 2016.

Leonard has spoken up in board meetings about how he believes department stores like Macy’s and Nordstrom are still key to selling Estée Lauder despite the widespread decline of malls and department-store shopping, people familiar with the discussions said. He has been reluctant to implement discounts or to embrace retailers like Sephora, Target and Amazon, believing they hurt the brands’ cachet.

When Leonard learned during recent strategy presentations that the company was going to sell its products in Ulta Beauty shops inside Target stores and on Amazon.com, he said he believed they were bad decisions, the people said. William and Freda joined forces: They and others have said brands like Clinique are geared toward the mainstream and should be sold at mass outlets to effectively compete in North America. In recent years, Estée Lauder has been cutting back its investment in department stores.

When William was on the way up, his father bristled at any hint of nepotism. “Except for a short period, he never worked for me, and he has never reported to me directly. He carried a [delivery] bag just like me; he did everything that I ever did,” Leonard said during a 2004 speech at Stanford University’s business school. Leonard paused, then shrugged. “Listen, I’m not my mother or father, and he’s not me.”

Jane went to Stanford, while Leonard, Ronald, William and Aerin attended the University of Pennsylvania.

Last month, Ronald said he may stop supporting the University of Pennsylvania, where he and his family are big donors over the school’s response to the Hamas attack on Israel. “I have spent the past 40 years of my life fighting antisemitism all over the world and I never, in my wildest imagination, thought I would have to fight it at my university, my alma mater and my family’s alma mater,” he wrote in a letter to Penn’s president.

When William initiated a search for a chief operating officer, he found his successor in Freda. Freda told William he’d like to be CEO, a confession that William “found liberating,” he said to Town & Country. He added at the time that he’s just as happy to run interference with his family members for Freda than do budget meetings.

“Leading a public company is a sentence, but leading a publicly held, family-controlled business is a life sentence,” William said in 2008. “I didn’t want to be taken out of here feet first.”

William recently paid $155 million to purchase a Palm Beach oceanfront estate that was the former home of Rush Limbaugh. He also recently listed two oceanfront parcels in Palm Beach, Fla., for a combined $200 million. In 2020, William sold his Beverly Hills, Calif., home to entertainment mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg for $30 million.

Leonard, who remarried in 2015 and splits his time between his luxurious Manhattan residence and his other homes, remains the family’s biggest shareholder, with a roughly 22% stake that is currently worth about $10.2 billion, according to FactSet.

Jane has been building her personal stake in recent years and is now the second-largest, with a 6% stake currently worth about $2.8 billion—larger than her cousin William’s. More than a decade younger than William, she has spent much of her career working at their grandmother’s business.

She joined the board in 2009, replacing her father Ronald, who later returned to it when his older daughter Aerin stepped down. In 2020, Jane was promoted to the newly created role of head of enterprise marketing and chief data officer.

Jane is the self-proclaimed methodical sister to her more social sister Aerin, who also launched her own lifestyle brand. Jane worked in advertising before joining Estée Lauder in 1996, saying she knew signing up with her family’s business would be a job for life. People close to her describe her as a disciplined and a hardworking leader. “I think about things. I plot out where I want to be and where I want to get to,” she said in an interview with Women’s Wear Daily in 2012.

Jane is married to former central banker Kevin Warsh, who also attended Stanford. Warsh was appointed to the Federal Reserve Board in 2006, when he was in his 30s. He is known for helping revive the U.S. financial system during the 2008 crisis.

Under Freda’s leadership, the company has diversified its business lines, acquired several brands, and added more structure and technology. The former P&G executive pushed growth into China, riding the country’s boom, which is now at the heart of Estée Lauder’s current challenges.

Since Freda took over as CEO in July 2009, Estée Lauder stock has surged from under $20 to above $300 in 2021, before its recent tumble down to below $125. During his tenure, Estée Lauder’s total return, including dividends, was about 780% through Thursday’s close, compared with around 900% for L’Oréal and 550% for the S&P 500 index, according to FactSet.

Freda and his management team have been briefing directors on a turnaround strategy, which focuses on clearing out unsold inventory. The CEO has set inventory goals for late March and late June that will be key tests of his standing with the family and shareholders.

Freda has told investors that he expects the company’s results to improve in 2024 and that its inventories in Asia will be in line with retailers’ needs by the end of the March quarter. He repeated those sentiments at Friday’s shareholder meeting, saying the recovery from the pandemic has been “prolonged and complex.”

In an interview in August, Freda said the past year had been challenging for the company, but said he remained confident about his position as CEO: “I don’t plan to go anywhere, we’re in the midst of a very important turnaround plan.”

Whoever is CEO, there is a lot of work ahead.

Profits at Estée Lauder, which also owns British fragrance label Jo Malone and luxury skin-care line La Mer, have plunged in recent quarters. Executives have several times had to lower their sales projections. They have largely blamed weak demand in Asia.

Estée Lauder and its brands have had success in mainland China, gracing billboards and welcoming shoppers at luxury malls. “We were one of the first companies to enter the Asian market,” Leonard said in 2020. “If you’re the first to market, you always win.”

The pandemic waylaid those ambitions.

The strategy was built around travel retail in Asia, including duty-free shops. Covid’s disruptions to travel in China and supply chains, as well as the country’s languid economic reopening and high youth unemployment have battered Estée Lauder’s sales. The company has struggled to attract the ever-discerning Chinese consumer, and local brands have been gaining market share.

“One of the challenges that Estée Lauder faces is the lack of true innovation,” said Milton Pedraza, head of the Luxury Institute consultancy. “Affluent consumers tell us they aren’t bringing much new in the market. They are bored.”

Data from consulting firm China Skinny shows that while Chinese consumers are still prepared to spend a premium on beauty, Estée Lauder hasn’t fully capitalized on that. Social-commerce retailers, such as China’s Douyin, continue to take away sales from traditional e-commerce platforms, said Mark Tanner, the Shanghai-based managing director for China Skinny.

Estée Lauder has been much slower at reading trends and adapting to them, Tanner said.

The company has said it still expects China will be a key driver of its long-term growth and has invested in its upgraded distribution network, new China innovation labs and a new manufacturing plant in Japan.

Estée Lauder made a roughly $1 billion investment five years ago in a new manufacturing plant in Japan, set to serve Chinese customers. That decision may hamper profits since the company is reducing production levels because of lower demand.

The company built the factory to eventually manufacture about 300 million units a year, but it is only expected to produce tens of millions of units in 2024 given lower demand. In the September quarter, the company posted about a 20% drop in skin-care sales, mainly driven by China.

Other big companies are confronting a China slump. P&G, which owns Japanese skin-care brand SK-II, and Tokyo-based rival Shiseido have recently posted sales declines in China.

In the U.S., some Estée Lauder brands are facing increasing competition from indie cosmetic lines known for having lower operating costs and social-media allure among beauty enthusiasts. Brands like e.l.f. Beauty are growing rapidly in the U.S. through marketing aimed at a younger TikTok audience.

At a Barclays conference in September, Freda said the company is looking to address its strategy to better connect with customers and their expectations, and asked for patience.

Another executive who is on the CEO successor short list is Stéphane de La Faverie, said the people familiar with the matter. He has worked closely with Freda and climbed the ranks over 12 years. He was named executive group president in September 2022, making him responsible for about half the brands.

The question of succession is often fraught for companies, but it is unique for Estée Lauder, which has to balance being a public company with family dynamics. Estée’s office high up in the General Motors Building on 59th Street and Fifth Avenue is still flawlessly preserved, replete with flowered wallpaper, tasseled silk curtains, wood and gold-plated furniture and pink chairs.

It is down the hall from Leonard’s office, and his son William’s—and Freda’s—are on the same floor.

Leonard has had a family photo from his son’s high-school graduation displayed in the center of a top shelf of his office, in between his mother’s autobiography and books on artists Georges Braque, Juan Gris and Pablo Picasso.

“I love family,” Leonard said in 2014. “They say you can’t choose them, but if I had the chance, I’d choose them all again.”

Write to Emily Glazer at Emily.Glazer@wsj.com and Sabela Ojea at sabela.ojea@wsj.com

—Natasha Khan contributed to this article.

Corrections & Amplifications

William Lauder’s stake in Estée Lauder is $1.1 billion. An earlier version of the family-tree graphic incorrectly said the stake is $1.1 million.