Crispín Mendoza bounded up the stairs to the roof of his house earlier this spring and shot back at the gunmen who were peppering his home with automatic-rifle fire. It was election season in the rugged mountains of lawless Guerrero state, Mexico’s deadliest place to run for municipal office.

Since January, when he began campaigning for mayor of the town of Alcozauca, Mendoza said he has endured dozens of telephone death threats. A local criminal kingpin, known as “El Señor,” left a message written on a sheet warning Mendoza to stay out of politics.

A short, stocky man with a neatly trimmed beard, Mendoza said he was asleep in the middle of the night in March when two gunmen started shooting up his home. As his wife and three children screamed and hid under a bed, Mendoza grabbed his Taurus 380 revolver.

“I started firing back,” he said. “I scared them away.”

Since the shooting, his neighbors have rallied to his defense, bringing their rifles and sleeping in his home, three at a time. Mendoza now has a detail of seven National Guardsmen, who protect him around the clock.

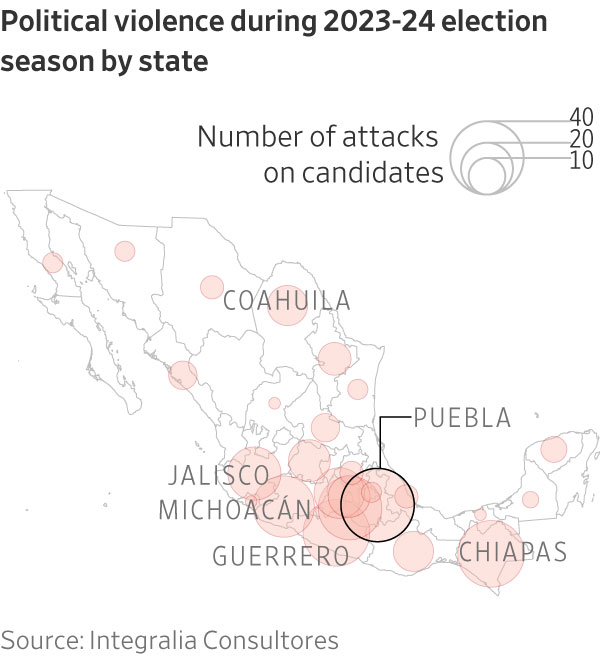

A wave of political violence has become a threat across Mexico ahead of the country’s national elections Sunday. More than 200 government officials, candidates and political party activists have been gunned down since Mexico’s electoral process got under way in September, according to Integralia Consultores, a Mexico City consulting firm.

While the presidency and both houses of Congress are up for grabs, organized-crime groups are particularly focused on thousands of local elections. Mexico’s electoral agency, INE, has requested federal protection for more than 550 candidates for public office because of threats or attacks.

“This election is going to be the most violent in history,” said Luis Carlos Ugalde, Integralia’s general director and former chief of Mexico’s electoral agency. “If you want to be a candidate in a region controlled by gangs, you need to ask for permission so they don’t kill you.”

Mendoza didn’t. He said he was drawn into politics to make a better life for his neighbors, many of whom live hardscrabble lives in homes that have dirt floors and no running water. The town is plagued by corruption, with criminal organizations stealing a good chunk of the money that should go to public works.

“Life is very nice here, except that when you want to do things right, there’s always people who want to block your path,” he said. “For many, the profit of being in politics is great.”

The tempo of violence has quickened ahead of Sunday’s election. Between May 15 and 17, three candidates running for municipal office in three states were killed. The bodies of a candidate for City Council in another Guerrero town and his wife were found in the back of a pickup truck. During the same period, the body of a candidate for a town in the Pacific coast state of Sinaloa was found in a field, and a candidate for mayor in a town in the southern Chiapas state was gunned down.

On Wednesday evening in the town of Coyuca in Guerrero state, near the once-glitzy beach resort of Acapulco, the opposition candidate for mayor, José Alfredo Cabrera, was gunned down as hundreds of his supporters watched in horror. He was shot twice in the head as he arrived to give his final speech at the closing rally of his campaign. The gunman, who had approached the candidate in a wheelchair, was immediately killed by Cabrera’s security guards, authorities said.

“Is it worth it losing your life, losing everything?” asked Mendoza after hearing about Cabrera’s killing. “Politics has become very dangerous.”

Guadalupe Taddei, president of Mexico’s electoral agency, recently told reporters that Mexicans can cast their votes freely Sunday. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador , who is limited by law to a single six-year term, said the acts of violence are isolated incidents that have been exaggerated by the opposition. He said there is good coordination between election authorities and his Security Cabinet. “Action is being taken everywhere,” he said at a recent news conference.

The wave of political violence has exposed the cracks in Mexico’s democracy. Polls show that security is a top concern for Mexican voters. Security experts have said that the six cities with the highest homicide rates in the world are in Mexico.

Organized-crime groups try to rig local elections as a way to control government budgets and public works, as well as the roads vital to smuggling drugs and migrants to the U.S.

On a municipal level, gangs work to elect mayors and name officials from public-works directors to police chiefs who play essential roles in looting the town treasuries and protecting the criminal groups’ operations.

“They select candidates or eliminate those they consider a threat for their business,” said Eduardo Guerrero, a security consultant in Mexico City. “They can contribute to the financing of campaigns and even mobilize voters on election day.”

Crispín Mendoza holds a meeting with members of the community in Xonacatlán, as a National Guard vehicle stands guard in front.

Gang violence and corruption is rampant in the communities that dot the mountains known for opium poppy crops near the Pacific coast in southern Mexico. Poverty in Alcozauca and other communities in Guerrero state has worsened since the boom in cheaply produced fentanyl collapsed the price of opium gum, used to make heroin, which competes with fentanyl, Mendoza said.

“Now a lot of people get by with a tortilla with sauce and salt,” he said.

Mendoza grew up in San Jose, Calif., where he attended college before returning to Guerrero 14 years ago. Back home, he fell in love with a local woman and started a business buying plots of land and building the dream homes for fellow townspeople who migrated to the U.S. with the hope of returning some day.

Death threats quickly followed after Mendoza denounced the siphoning of funds from public projects. Callers rang him up almost daily to tell him he would be killed if he continued, he said.

Other candidates in Mexico have paid with their lives for speaking out. In the central Guanajuato state, home of oil refineries that feed a booming black market in fuel, the mayoral candidate Gisela Gaytán ran on a platform of reducing violence in her crime-ridden city of Celaya.

Gaytán twice refused offers from the local gang there to fund her campaign in return for installing a police chief friendly to the group, according to David Saucedo, a security consultant for political candidates familiar with her campaign. Celaya, a city of some 500,000 people, has the world’s highest murder rate, according to security experts. Cartel gunmen shot Gaytán dead as she greeted voters on the streets earlier this spring. Authorities said they have detained a half-dozen suspects, but no one has been charged.

Mexico’s political violence has spread to the country’s well-guarded capital, where in May a gunman attacked a candidate locked in a tight race to head a Mexico City borough.

Alessandra Rojo, a feminist activist, was sitting in the back seat of her SUV in central Mexico City when a gunman fired five shots from across the street into the parked vehicle’s rear door, according to surveillance video released by authorities. Her driver floored the gas pedal, and Rojo was unharmed.

“I thought they had hit me,” said Rojo, the candidate of the main opposition coalition. “I was hyperventilating, I was vomiting.” Two suspects have been detained in the case, police said.

Rojo said the gunman might have been sent to scare her off. Police have provided her with a security detail. She has continued to campaign.

“Things need to change here,” Rojo said.

Sandra Velázquez, the mayor of Pilcaya, a small town in Guerrero state and home to one the largest cave systems in the world, a popular tourist attraction for Mexicans, got into trouble in 2021. She politely turned down a meeting with a local gang boss and bought land to build a base for the National Guard to improve local security. On her way to sign the deed, Velázquez’s bulletproof car was ambushed. Three police officers were killed.

“I started to pray and threw myself on the floor,” she said. The close call stopped her plans to continue her political career by running for Guerrero’s Congress. Too dangerous, she decided.

“They now control everything, from public services to transportation, even beer and soft-drink distribution,” Velázquez said of the local criminal organization. “Cops must work for them as lookouts, providing detailed information about everything that happens in the community.”

The interference of organized crime in elections has been largely confined to municipal levels, said Lorenzo Córdova, who led the election agency from 2014 to 2023. Violence hasn’t stopped Mexicans from going out to vote, he added.

Write to José de Córdoba at jose.decordoba@wsj.com and Santiago Pérez at santiago.perez@wsj.com