“USA250 : The Story of the World’s Greatest Economy” is a yearlong WSJ series examining America’s first 250 years. Read more about it from Editor in Chief Emma Tucker.

America has officially been in existence for nearly 250 years. Motion pictures have been around for less than half of that, but few inventions have been as effective at telling the story of America and its value.

“American movies are a sort of Rorschach of the culture,” says Nell Minow, a longtime film critic and author of “101 Must-See Movie Moments.”

This list of essential movies from each decade begins with the 1910s—apologies to fans of Edwin S. Porter’s 11-minute “The Great Train Robbery” from 1903—and leans heavily on box-office receipts as a popularity metric. But it also includes bijou bombs that later found fans (see: 1982’s “Blade Runner”) and excludes blockbusters that lack cultural resonance. (Can you even name a character you loved in “Avatar”?)

These films cut across themes, genres and villains, and yet all tell us something about what it means to be an American, and the collective American head space at the time they were released. “If America is analyzed as a film genre, it would be a melodrama,” says Desson Thomson, a Washington Post staff critic for 20 years. “America puts into its movies what it is feeling very directly.”

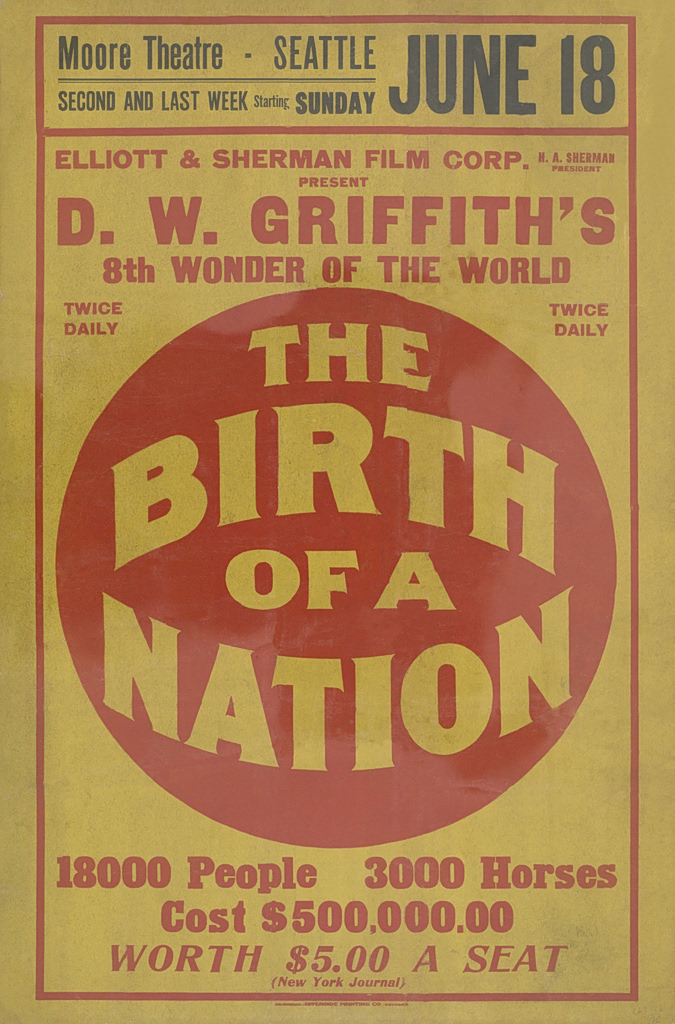

1910s

“The Birth of a Nation” (1915): D.W. Griffith’s film, often referred to as the first feature-length film, at 192 minutes, is also considered American cinema’s most racist film. Based on the play “The Clansman,” and the 1831 uprising of a slave community, it reflects their Jim Crow-era struggles.

“Intolerance” (1916): Another D.W. Griffith film, with four separate stories of intolerance, spanning 2,500 years and using groundbreaking cinematic techniques, it is Griffith’s reaction to the backlash to the racism in his “Birth of a Nation.”

Also: “Wild and Woolly” (1917) satirizes the romance of the Wild West as the frontier era is ending. “Stella Maris” (1918) centers on women’s lives and social disparities as World War I sees more women working in Hollywood filmmaking.

1920s

“Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans” (1927): A silent film, it is notable for its pioneering synchronized score and sound effects that enhanced a love story about the temptation of glitzy city life in the new, freer flapper era. It is accompanied by the first talking newsreel, giving it a box-office boost, and won three Oscars.

“The Jazz Singer” (1927): A tale of rebellion—a son who wants to sing in a saloon rather than a synagogue—it reflects the many second-generation immigrants shaking off old-world expectations for modern, secular lives. Though often remembered for Al Jolson’s “Mammy” blackface performance, it is groundbreaking as a cinema “talkie.” It receives only an “honorary” Oscar, as its new Vitaphone technology is thought to give it an unfair advantage in other categories.

Also: “Safety Last” (1923), in which Harold Lloyd’s ambitious striver hangs from a skyscraper’s clock, as urban skylines are growing alongside workers’ ambitions and frustrations.

1930s

“Modern Times” (1936): At a time when unemployment and paranoia about communism were both high, Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp literally gets pulled into the gears of the factory machine and bumbles into police skirmishes, blending slapstick and social commentary.

“You Can’t Take It With You” (1938): A corporate titan reconsiders his ways in this class-differences rom-com, a not-surprisingly popular theme in the Great Depression. Based on the Pulitzer-winning play, it is a box-office success and earns Frank Capra his third Oscar directing award.

Also: “Jezebel” (1938) examines women defying norms by setting the story in the Antebellum South with its antiquated expectations for proper Southern belles; Bette Davis takes home an Oscar for it.

1940s

“Citizen Kane” (1941): Some critics call this movie a master class in technique, but it’s also a treatise on the power of the media and the wealthy—all from a 25-year-old Orson Welles. Based on William Randolph Hearst, whom audiences would have seen using his media empire to blast FDR and his “raw deal,” the film shows great riches coming at the cost of true happiness.

“Casablanca” (1942): This wartime drama is well-timed: The release date is pushed earlier to take advantage of the actual capture of Casablanca. Combined with its very American, “easy, can-do spirit,” says Minow, and its Hollywood star-system casting of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, it remains popular today.

“The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946): One of the first popular movies about the struggles of re-entry for military men returning home, it wins the best picture Oscar for director William Wyler and is one of the highest-grossing films that year.

Also: “Rebecca” (1940) reflects the uncertain role of women in the interwar period via a woman living in the shadow of her husband’s former wife in Alfred Hitchcock’s first American film. “Bambi” (1942) gives wartime audiences an escape to nature and the animated world, sourced from a novel banned by the Nazis.

1950s

“On the Waterfront” (1954): This story of life on the New Jersey docks features people standing up to the machine, in this case businesses, unions and the mob, echoing newspaper headlines of the time. Director Elia Kazan’s crime drama takes the Oscar and Marlon Brando also wins for his portrayal of dockworker Terry Malloy.

“The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957): This war film, an American-British co-production, examines the treatment of POWs forced to erect a supply bridge by their Japanese captors, takes seven Oscars and audiences love its gripping test of wills and physical endurance.

William Holden and Chandran Rutnam while shooting The Bridge on the River Kwai. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Also: “All About Eve” (1950) comes as the Hollywood star system is waning, but audiences remain obsessed with the pursuit of fame. “Rear Window” (1954) brings a focus on urban alienation as cities grow and neighbors become anonymous.

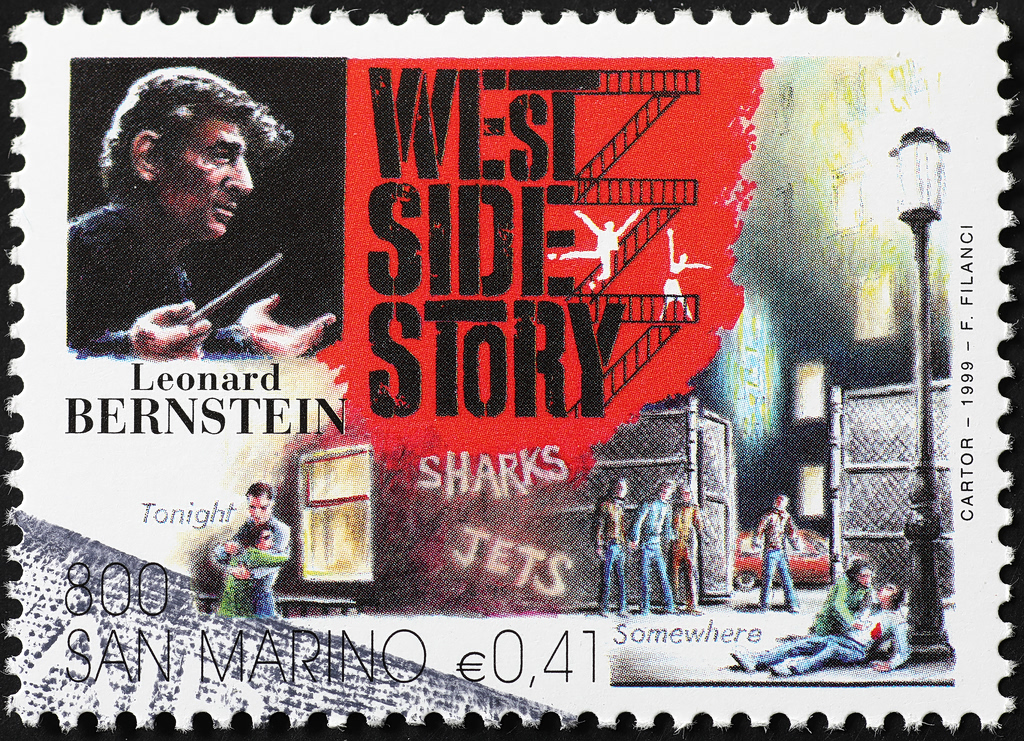

1960s

“West Side Story” (1961): This Romeo and Juliet tale of Tony and Maria and rival gangs, the Sharks and the Jets, takes 10 Oscars, as old dynamics play out with new immigrant groups arriving in the American melting pot. (Natalie Wood as Puerto Rican gives some modern audiences pause.)

“ Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969): Some critics chafe at this reinvention of the classic western, but rebellion-minded audiences love the charming chemistry between Robert Redford and Paul Newman and the Oscar-winning score from Burt Bacharach.

Also: “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) gives audiences antiheroes to project their counterculture angst onto, while in “The Graduate” (1967), Dustin Hoffman’s character channels a young generation’s disillusionment with materialism and sexual convention.

1970s

“The Last Picture Show” (1971): Critic Roger Ebert’s review quips that it was the best film of 1951, making the point that director Peter Bogdanovich doesn’t simply use period details and songs to create nostalgia, but goes further by creating the visual feel of the era in his black-and-white film about the hollowing out of small-town America.

“The Godfather Part II” (1974): Critics didn’t universally love the second of Francis Ford Coppola’s film trilogy. Yet the flashback sequences to Vito Corleone’s arrival in America give it resonance for a country built on immigration, and the film is now almost universally considered the best of the three.

Also: “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975) appeals to a generation questioning institutions’ power over individual freedoms. “Rocky” (1976) is the underdog guy whom cynical audiences are craving in the era of Watergate. “Network” (1977) speaks to audiences concerned about the effect of media-company consolidation and the move to “infotainment.”

1980s

“Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981): American film has no shortage of swashbucklers, but audiences especially love the idea that an everyman, in this case Harrison Ford as an archaeology professor, can become an action hero who races against Nazis to score a biblical artifact and save the world. “Raiders” also ushers in an era of box-office action movies with financially successful sequels.

“Do the Right Thing” (1989): When it is released, some suggest Spike Lee’s movie will spark riots with its focus on the complexities of race relations in one Brooklyn neighborhood. Instead, it sparks conversations that continue today. It brings multidimensional Black characters, a nuanced depiction of the barriers to doing the right thing, and predicts the anger simmering years before the Crown Heights and Los Angeles race riots.

Also: “Tootsie” (1982): The gender-bender plot illustrates, with sharp hilarity, society’s biases in the workplace, a decade before Anita Hill and the Smith Barney “boom-boom room.” “Blade Runner” (1982) finds success only later, as audiences of the fast-pace 1980s find it slow and brooding. “Kramer vs. Kramer” (1979), with divorce rates on the rise, mirrors the changing role of fatherhood, with Meryl Streep and Dustin Hoffman as the grappling parents.

1990s

“Boyz in the Hood” (1991): The coming-of-age story of friends in the growing gang culture of South Central Los Angeles isn’t only a financial success—launching the careers of a half-dozen Black actors—but it sees John Singleton become the youngest filmmaker and first Black person to be nominated for a best-director Oscar, signaling an era in which creators of color began to have a place at the table.

“Pulp Fiction” (1994): Quentin Tarantino’s wild, violent tale sweeps in as part of the 1990s indie boom. Structurally and tonally, it’s a far cry from the crowd-pleasing American blockbusters of the 1980s, yet it is a box-office success and reflects that audiences were ready for artier movies as mainstream entertainment.

Also: Both “Fight Club” (1999) and “The Matrix” (1999) reflect consumers’ fears at the dawn of the digital age, and anxieties around corporate power.

2000s

“ There Will be Blood” (2007): Paul Thomas Anderson directs Daniel Day-Lewis as a ruthless prospector clashing with a hypocritical preacher—a decade after the fall of televangelists Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart—in the California oil boom in a tale of greed, capitalism and the American dream gone rotten.

“The Dark Knight” (2008): Post-9/11 unease breeds the desire for heroes, and the second film of Christopher Nolan’s resurrected Batman, with the addition of actor Heath Ledger as the Joker, brings a wild operatic sweep to the franchise and adds to the rise of the superhero genre in general.

Also: “The Departed” (2006) sees police captain Alec Baldwin chanting “Patriot Act! Patriot Act! I love it! I love it! I love it!”—leaving no mystery to the political winds of the time. “Moneyball” (2011), with its sabermetrics approach to baseball, reflects the rise of consultancies and data-driven decision-making.

2010s

“12 Years a Slave” (2013): The unflinching, brutal true story of a man born free, captured and sold into slavery, it reflects the position that electing a Black U.S. president didn’t make America post-racial.

“Get Out” (2017): Filmmaker Jordan Peele brings a psychological horror movie twist to race relations, as a Black man has a bizarre encounter with his white girlfriend’s family, using horror tropes to suggest a dark side to performative white allyship.

Also: “Gravity” (2013), through Sandra Bullock’s lone experience in space, shows the isolation and loneliness epidemic of the modern high-tech world. “Brooklyn” (2015) uses a historical setting to highlight the emotions around the immigrant experience, premiering the same year as the European refugee crisis.

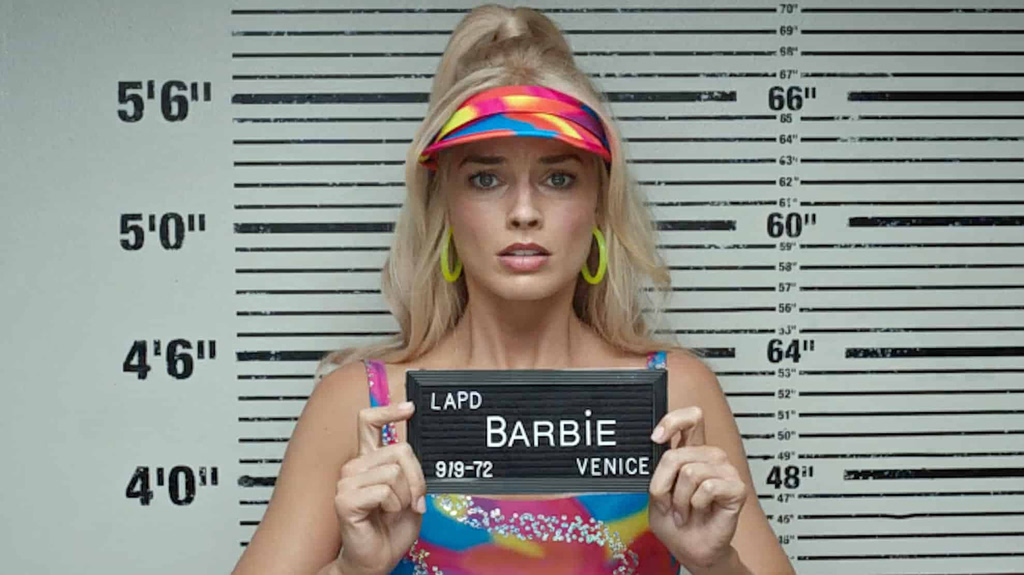

2020s

“Oppenheimer” (2023): This ambitious film about J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, is released as media headlines dub the AI boom an “Oppenheimer moment” of technological advancement and ethical dilemmas.

“Barbie” (2023): The other half of the “Barbenheimer” phenomenon, filmmaker Greta Gerwig creates a playful comedy to analyze the expectations placed on modern American women, at a time when postpandemic audiences are craving nostalgic, empowering experiences.

Also: “Everything, Everywhere, All at Once” (2022) highlights the digital overload of modern life, along with the pressures within Asian-American communities. “Killers of the Flower Moon” (2023) is released the same year the Supreme Court affirms the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act, and Native American communities confront problems with voting access.

Write to reports@wsj.com