In the heart of one of the world’s top vegetable-growing regions in California, scientists are on a mission to save ketchup.

Plant breeders at the Woodland, Calif., facility of German pharmaceutical and agriculture giant Bayer are testing whether tomatoes meant for processing into pizza sauces and ketchup can survive on a fraction of their traditional water needs, without sacrificing taste or juiciness.

Using a small set of tweezers, Taylor Anderson carefully removes the part of a tomato plant that allows it to self-pollinate. He extracts pollen from the flower of a second plant and places it on the first, creating a new hybrid.

Anderson, a vegetable breeder at Bayer, leads a team that is mixing and matching tomato varieties that have historically done well under drought conditions or have a stronger root system, aiming to produce varieties capable of growing with 20% or 50% less water.

“We haven’t hit the doomsday scenario of just not having just enough water to do our basic agricultural needs,” says Anderson, “but that day is coming and it’s coming soon.”

Bayer’s tomatoes are one example of how the agriculture industry is now trying to stay ahead of a changing climate that could disrupt the food supply chain and drive up prices for consumers.

Partly it is defense. Droughts and rising temperatures globally have taken a heavy toll on agriculture in recent years, and some scientists and agriculture officials expect a changing climate to make extreme weather events more common.

In California, droughts and severe weather conditions in recent years have wrecked some of the state’s most valuable crops, such as tomatoes, almonds and alfalfa. California produces more than 90% of U.S. processing tomatoes, used for sauces and pastes.

That is powering a race among seed companies, where executives say they are harnessing their billion-dollar research and development budgets to create hardier crops. Those efforts include less-water-intensive rice and shorter corn that can handle higher winds, as well as chemicals to battle pests that spread in warmer temperatures.

“There is a unique sense of urgency,” said Bayer’s head of vegetables R&D, J.D. Rossouw——to stay ahead of the changing climate, and the competition.

At Kraft Heinz, executives said conditions in California have prompted the ketchup maker to consider Washington state for growing tomatoes needed to help produce the seeds for 40% of all tomato products sold in grocery stores worldwide.

“It is very hard right now,” said Kraft Heinz CEO Miguel Patricio in an interview. “There’s a lack of tomatoes in the world.”

It can take companies more than a decade to develop new seed varieties, and there is no guarantee they would be enough to help farmers mitigate the effects of climate change in the long term. Developing hardier plants is one way to help farmers cope without migrating crops from one growing region to another, which would be excruciatingly difficult or impossible, industry officials say.

Moving crops would require purchasing new equipment that could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, said Jeff Rowe, incoming chief executive of seed and pesticide company Syngenta. The supply chain infrastructure and processing plants built around crops such as corn and soybeans in the Midwest would have to completely change, he said.

“Innovation has never been more important,” Rowe said.

The industry has already spent years developing drought-resistant corn and soybeans, specifically by focusing on creating stronger root systems. More resilient plant genetics have been credited by analysts with helping the two largest crops in the U.S. survive hotter and dryer growing conditions in the Midwest this summer.

“The challenge we’re facing is the speed at which it (climate) is changing,” said Wendy Srnic, seed company Corteva’s vice president of biotechnology, referencing various issues farmers are facing.

Corteva is working on new corn varieties that can be grown in places that were previously too cold, such as western Canada. Syngenta is developing new pest-resistant cabbage for European farmers meant to stave off insects and diseases once unique to Africa but that have spread north from climate change, the company said.

California farmers are eager for a solution. Jim Beecher produces roughly 160,000 tons of tomatoes a year 45 miles southwest of Fresno, Calif. He says most Americans have probably tasted his tomatoes, which will eventually be turned into ketchup for Kraft Heinz.

Drought the past few years has made it hard for Beecher to make his farm profitable. Some members of his family business have talked about selling the farm, he said.

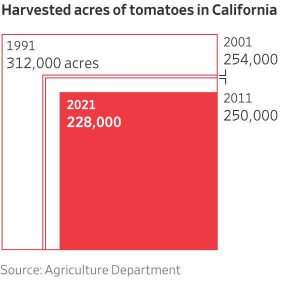

Planting acreage for processing tomatoes fell more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, largely because of persistent drought in the region, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. If water becomes more scarce, the long-term viability of California tomatoes could be in jeopardy.

“It’s been dire,” Beecher said, adding that more resilient tomato varieties are one of the few solutions that will keep tomato production in the area viable long term.

Bayer’s efforts to improve tomato seeds revolve around traditional plant-breeding techniques, crossing two plants to produce offspring that share the best characteristics of their parents. Over the past few months, Bayer’s Anderson observed about 40 new breeds of tomato in hundreds of plots, testing them under different growing conditions, such as 20% or 50% less water. The three or four breeds that perform best will move to the next round of testing in 2024.

So far, Anderson said, the results are promising. The physical appearance of plants weren’t markedly different and none had shriveled up and died. If successful, Anderson estimates that based on current testing it is possible the seeds could save California farmers roughly 34 billion gallons of water a year, assuming they are broadly adopted.

He said his team even contemplated ramping up the challenge by testing the tomatoes’ performance in places like Yuma, Ariz. Finding the right match of tomato genetics and testing their effectiveness could still take years, Anderson said.

—Jesse Newman contributed to this article.

Write to Patrick Thomas at patrick.thomas@wsj.com