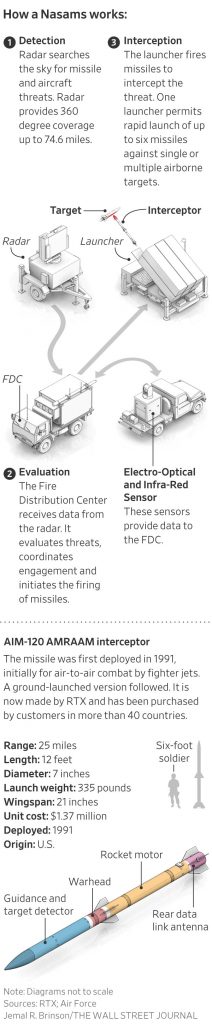

KONGSBERG, Norway—A factory here west of Oslo produces a missile-defense system that can shoot down drones, helicopters and other airborne threats from almost 25 miles away.

Capable of launching 72 missiles into the sky at once, the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System, or Nasams, is what protects the airspace over the White House. When first deployed in Ukraine in 2022, it recorded a 100% success rate shooting down cruise missiles and drones in its first few months.

With the West confronting a rising number of potential threats, including Russia and China, orders are piling up for the Nasams from Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace.

“I’ve never seen anywhere near so much demand,” said Eirik Lie, a 30-year Kongsberg veteran who is president of the company’s defense unit, on a November tour of the factory.

New customers, though, will have to wait: It takes two years to make one Nasams, and there is already a multiyear backlog.

The Ukraine war has highlighted the West’s deficiencies in quickly producing more weapons at a time of need. The Gaza conflict may tighten supplies for certain armaments.

The constraint is particularly acute for missiles and the systems that defend against them, and also guard against the swarms of drones that have become a central element of modern warfare.

On Wednesday, NATO said a coalition of members, including Germany and the Netherlands, is buying up to 1,000 Patriot missiles, or $5.5 billion worth, to strengthen their air defenses amid Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Kongsberg, which in addition to Nasams also makes products including ship-based missiles and parts of F-35 fighter jets, has ramped up production. It moved to 24-hour, seven-day shifts and has workers in for some holidays when the factory would typically have been idled for maintenance. That still may not be enough.

The problem is that modern weapons are hugely complex, often requiring thousands of parts. Kongsberg, like most Western defense firms, designs and assembles its weapons systems but doesn’t manufacture most of the components. Over 1,500 suppliers contribute to the products at this factory. The Nasams supply chain alone consists of over a thousand companies and is built across two continents, with the U.S. defense contractor RTX, formerly known as Raytheon Technologies, supplying the radar and the actual missiles.

Pointing at a partially assembled Nasams, Lie said: “We are supplied by companies with their own supply chains, which in turn have their own supply chains, which have their supply chains, till it gets right down to the mine that digs up the basic resources.”

The defense industry is also grappling with a prolonged labor crunch, as it scrambles to find workers with niche skills, from software development to welding, and who are willing to endure lengthy security checks.

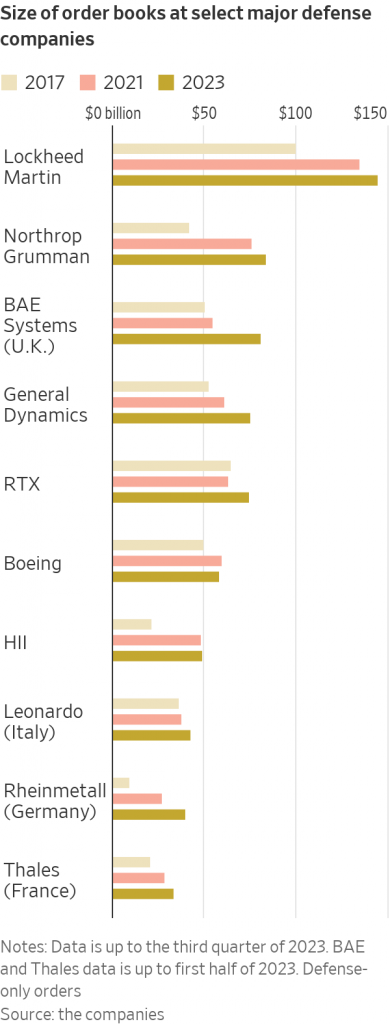

While flush with higher defense budgets, the West hasn’t faced the same supply constraints since perhaps the Korean War, some military analysts say. Ten of the West’s largest defense companies alone are currently sitting on order books worth over $730 billion, up around 57% from the end of 2017, when demand started ramping up.

“We all have to increase our production,” said Pentagon acquisition chief Bill LaPlante at a November conference. He held one hand high and the other low and said: “The worldwide demand is here, the ability to supply is about here.”

Leading U.S. and NATO officials are increasingly raising concerns that the shortages will affect their ability to fight.

In a wargame simulation published in early 2023 of how the U.S. would respond to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the Center for Strategic & International Studies estimated America would run out of all-important long-range antiship missiles within the first week.

The U.S. wouldn’t be able to replenish its stock quickly: As with the Nasams, each missile takes about two years to make.

Other missile categories have similar issues. Lockheed Martin and RTX said in 2023 it will take four years to double production of Javelin and Stinger surface-to-air missiles, twice as long as expected, as supply-chain challenges continue. While companies have blamed shortages of solid rocket motors for the issue, Pentagon officials said the problems were more widespread, with everything from chips to springs and ball bearings running short.

The U.S. Department of Defense tried to track the global supply chains for the two missiles with the goal of finding workarounds for bottlenecks, said Michael Vaccaro, who oversees industrial base strategy for the Pentagon, at a recent industry conference. His conclusion was sobering: “We do not have that ability.”

There are also long delays for delivery of other weapons, including the F-35 fighter jet, new training and refueling aircraft, and the latest U.S. aircraft carriers.

A spokesman for the Pentagon said the U.S. defense industrial base can continue to support Ukraine and Israel while ensuring the country’s readiness in the Indo-Pacific region, all of which have different weapon requirements.

A bomb squad member works next to a part of Russian missile at the site where residential buildings were heavily damaged during a Russian missile attack, amid Russia’s attack on Ukraine, in central Kharkiv, Ukraine January 2, 2024. REUTERS/Sofiia Gatilova

Mini fighter jets

Much of the West’s ability to make weapons, particularly in Europe, has been eroded as defense budgets fell after the Cold War and by gradual deindustrialization.

German companies could churn out up to 400 tanks a year at the height of the Cold War, but can now build only up to 50 a year, according to Nicholas Drummond, a defense consultant.

Modern weapons also just take longer to make and cost more money, which can keep a cap on inventories and extend the time it takes to replace them.

Missiles are like mini fighter jets, with complex electronics and guidance systems, said BAE Systems Chief Executive Charles Woodburn in a November interview.

Missiles have been used since World War II but became a key part of warfare in more recent combat, such as the first Gulf War and NATO’s intervention into conflicts that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia. Recent wars began with a barrage of missiles and rockets, including in the Middle East, where Hamas fired 3,500 rockets into Israel as its soldiers piled into the country on Oct. 7.

The threat from the sky has expanded due to the prevalence of drones—both the remotely piloted aircraft that can deliver Hellfire and other missiles as well as hobbyist-type drones with smaller explosives—and the development of hypersonic missiles that can fly more than five times the speed of sound and maneuver to their target, making them harder to shoot down. Russia and China have outpaced the U.S. and Europe on some missile and defense systems.

Those countries have hypersonic missiles, said Pentagon officials, while the introduction of the first by the U.S. has been pushed into 2024 following a test failure. U.S. and European systems to defend against hypersonic missiles won’t enter service for at least 10 years.

Russia and China together have around 5,020 land-based air-defense missile systems, compared with around 3,200 fielded by the U.S., Europe and Japan combined, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a defense think tank. The report didn’t assess quality or count shoulder-fired or naval-based systems.

Defense companies in China and Russia are mainly state owned so are less prone to the commercial pressures of those in the West. China’s giant manufacturing sector means it has a large domestic supply chain and plenty of graduates trained for the industry.

Predictions that Russia would soon run out of missiles in Ukraine were incorrect. In November, Ukrainian intelligence estimated that Russia is able to produce about 100 total of two different types of cruise missile, four Kinzhal hypersonic ballistic missiles and five ballistic missiles every month.

U.S. and South Korean officials said North Korea has also been supplying missiles, rocket launchers and shells to Russia to support its war in Ukraine.

China’s inventory has gone up from what analysts said was a handful of nonnuclear ballistic missiles in 1996, to what the U.S. now estimates is more than 3,000 ballistic and cruise missiles.

In a report to Congress, the Defense Department concluded that most of China’s missile systems are comparable in quality to other global “top tier” producers and that the country possesses one of the world’s largest forces of advanced long-range missile systems.

For the West, the challenge of supporting allies engaged in separate global conflicts is pinching supplies further, boosting demand for some weapons systems, notably artillery shells and missile defense, said Pentagon officials.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky told Western ministers in October that his country needs missile-defense systems most. Currently, the West doesn’t have large inventories to share, and these weapons are the main overlap with what Israel needs.

The U.S. has sent its two Israeli-made Iron Dome defense systems and the interceptors used to down missiles back to Israel.

In November, Zelensky told reporters that the war in Gaza had already slowed deliveries of artillery shells to Kyiv.

Israel’s Iron Dome anti-missile system intercepts rockets launched from the Gaza Strip, as seen from the city of Ashkelon, Israel, October 9, 2023. REUTERS/Amir Cohen

Orders after Ukraine

Lie said the uptick in orders for Nasams began in the years after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. Missile orders jumped after 2022’s full scale Ukraine invasion, and concerns over China are starting to show in order books as the U.S. Navy and others buy ship-based missiles, he said.

Kongsberg’s defense order book, at around $5.5 billion, is around six times the size of levels before 2018.

Hungary ordered six Nasams in 2020. The first two only arrived in October. Since Hungary’s order, the U.S. Army has ordered six more for Ukraine, which started arriving there in the summer, and five other countries, including Taiwan, have gone public with interest in buying the system.

Faced with increased tensions with China, Asian nations are developing their own missile capabilities “because of limited U.S. production,” said Bang Jong-kwan, a former South Korean Army Major General.

In 2022, Taiwanese officials publicly complained of U.S. delays on deliveries of Stinger antiaircraft missiles, alluding to supplies for Ukraine as being behind the holdup. In October, the chairmen of two separate U.S. congressional committees sent a letter to Secretary of the NavyCarlos Del Toro, questioning him over “alarming delays” to weapons deliveries to Taiwan, including antiship missiles. They were ordered in 2019, with the first batch finally arriving in spring 2023.

The Navy declined to comment.

Taiwan began mass producing a new domestic long-range land-based missile in 2021, and the country has three other types of long-range missiles in development, Taiwanese officials say.

Most Western defense companies say they are expanding capacity, particularly in shells and missiles. The U.S. government is investing in its domestic production base and bringing production of vulnerable components such as microchips home.

The Pentagon is set to roll out in coming weeks a new industrial-base strategy to help clear supply-chain logjams. Vaccaro, the industrial strategist at the Pentagon, said it will aim to map global supply chains for 100 weapons systems in production, down to part number and country of origin. The move is intended to identify pinch points early, and mitigate them through, for example, finding alternative suppliers.

U.S. defense giants are also increasingly building abroad with foreign partners, including for missiles, as a way to expand capacity for systems.

On a recent visit at Kongsberg, workers lowered parts for the Nasams from a ceiling crane onto a factory floor already filled with large castings of green metal. Shelves lined one of the walls, crammed with thousands of small parts.

In the 1980s, Kongsberg would make computer hardware for its weapons; now this is bought off the shelf. Around 15 years ago, the 200-year-old company did its own welding, now other companies do it.

When all its supplies of components are in place, Kongsberg can put together the mobile command center of a Nasams—the complex decision-making hub at the center of the system—in a month.

To manage the risk of its supply chain being broken, the Norwegian company has been building up stockpiles of essential components while holding spare Nasams to be sent to customers quickly if needed.

The company is also increasingly trying to find alternative sources for as many supplies as possible, giving it an option should one part not show. It said it will open a new factory at its site next June that will use a more-efficient assembly line. The company expects the method will increase its production of missiles by up to 10 times.

—Noemie Bisserbe contributed to this article.

Write to Alistair MacDonald at Alistair.Macdonald@wsj.com, Doug Cameron at Doug.Cameron@wsj.com and Dasl Yoon at dasl.yoon@wsj.com