Many airline passengers still don’t know how to behave.

A passenger on a Southwest Airlines flight waiting at the gate in New Orleans last month opened an emergency exit, climbed onto the plane’s wing and jumped to the ground, police said. An American Airlines customer service manager was hospitalized late last month after a passenger being removed from a flight in Miami punched her in the face and pushed her down, her head striking the jet bridge.

In July, a United Airlines flight to Amsterdam was diverted when a business class flier launched into a tirade after discovering his preferred meal wasn’t available. In South Korea in May, a passenger opened his aircraft’s emergency exit midflight, forcing the jet to land.

In-flight disruptions that range from annoying to dangerous are still happening at worrisome levels, regulators and airlines say, over a year after airlines dropped a contentious mask requirement—a major reason behind a surge in onboard conflict in 2021.

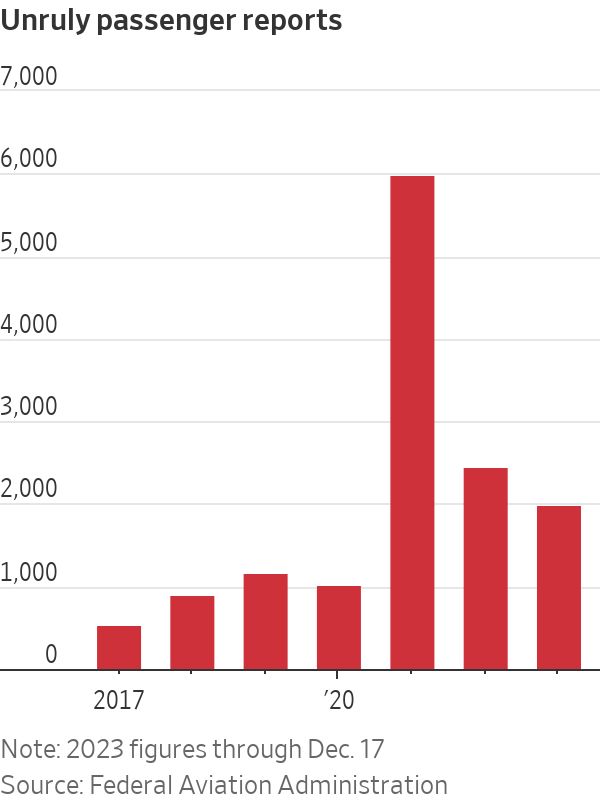

The Federal Aviation Administration has recorded nearly 2,000 reports of such incidents so far this year, up 71% from 2019’s full-year tally, though lower than 2021’s unprecedented peak of 5,973 incidents.

The Transportation Security Administration said it had opened 374 investigations into passengers interfering with checkpoint screening in the 2023 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30, up from 287 the previous 12 months.

“Airports and what happens on airplanes are kind of a microcosm of what’s happening in society,” said Michele Freadman, a former Massachusetts Port Authority security executive who is involved in federally funded research on passenger disruptions. “We see this violence and tendency to be angry in so many different venues.”

Regulators are warning that passenger unruliness poses a significant risk to flight safety, either by passengers directly interfering with aircraft—by attempting to open doors, emergency exits or accessing the cockpit—or by preventing cabin crew from performing safety duties. At minimum, incidents can delay flights, forcing planes to return to the gate or sometimes divert.

“When a passenger does not behave properly, it’s a safety risk,” Luc Tytgat, acting executive director of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, known as EASA, said in an interview.

“Not endangering your fellow passengers is kind of the bare minimum here,” U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said this week, admonishing travelers not to mistreat airport and airline workers ahead of the winter holidays. “Let’s say in addition to not assaulting anyone, be nice to them.”

Industry officials, unions and regulators say they have no clear reason for the continuing trend. Mental health is one factor, and drugs have played a role in some events, investigators say.

In October, Joseph Emerson, an off-duty Alaska Airlines pilot, was riding in a cockpit jump seat when he told pilots “I’m not OK,” and allegedly attempted to shut down the plane’s engines midflight, according to federal and state criminal complaints. He told authorities that he had taken “magic mushrooms” about 48 hours before the flight and that he had struggled with depression, according to court documents.

A Multnomah County, Ore., grand jury indicted Emerson this month with one count of endangering an aircraft in the first degree and 83 counts of recklessly endangering another person. He pleaded not guilty, and his lawyers have said he never intended to hurt anyone or put anyone at risk.

Some attribute the increase in troublesome behavior to a higher prevalence of prescription medication that has mixed badly with the reintroduction of alcohol on flights. Others say passengers are still rusty and nervous after an extended break from flying, or overwhelmed by the stresses of full planes and delays.

“They’re certainly down significantly from the peak of Covid, which is really good to see. But there still are events that are out there happening,” said David Seymour, American’s chief operating officer, in an interview last month.

On Oct. 25, a JetBlue passenger on a flight from Amsterdam to New York announced to a line of passengers waiting to use the toilet stalls that he refused to wait. He proceeded to relieve himself in a bottle at his seat before launching into a verbal assault against two cabin crew. The captain chose to divert the aircraft to Boston.

Tyesha Best, a union leader and cabin crew member for JetBlue Airways, said it was one of the more severe passenger incidents experienced by JetBlue colleagues this year, some of which deteriorated into physical violence.

“If we are more worried about an unruly customer that means we’re not worried about all the other customers on the plane,” Best said. “They’re compromising our ability to have a completely calm, a completely safe cabin.”

Best said flight attendants are calling for companies to do more to prepare crews to anticipate and handle violent customers, including providing additional self-defense training.

Sotiria Anagnostou’s flight from Milwaukee to Phoenix had to make an unplanned stop in Kansas City, Mo., last month to deal with a passenger disturbance. The passenger was agitated almost from the outset, Anagnostou said, and flight attendants seemed rattled as she became more verbally aggressive.

“We were all getting the impression she was very out of touch with reality, some kind of mental break,” Anagnostou said. “I was concerned something more severe was going to happen.”

In Europe, airlines and airports are rolling out new practices to try to limit the risk of unruly behavior during the flight. A handful of airports are providing smoking zones so that travelers can smoke before boarding, and not on the aircraft, according to EASA’s head of safety promotion, John Franklin.

Iceland’s national carrier has instructed its boarding staff to ask themselves, “Would you be happy for this passenger to sit next to a child you care about?” before waving a customer through the gate, Icelandair security manager Polly Hilmarsdóttir said at the DISPAX World conference in October. Dutch flag carrier KLM Royal Dutch Airlines this month said incidents at its gates and onboard its aircraft had doubled to 30 a month this year compared with 15 in 2019.

In the U.S., passengers who act out on planes can now face stiffer penalties as the FAA and Justice Department have sought to crack down on misbehavior. FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker said Tuesday that the agency has a “zero tolerance” approach toward such cases.

Nearly 750 passengers have been disqualified from TSA PreCheck since late 2021 after being referred by the FAA for misbehavior, in addition to passengers who lost access to the program after causing disruptions at TSA checkpoints, TSA said.

The FAA has referred more than 270 of the most serious cases to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for potential criminal prosecution, including 39 through the first half of this year.

A federal judge last month ordered a Hawaii woman to pay nearly $39,000 in restitution to American Airlines after she pleaded guilty to interference with a flight crew member. She was sentenced to time served of about 3½ months, followed by three years of supervised release during which she won’t be able to travel on commercial flights without approval.

According to her plea agreement, the passenger used profanity and threatened the crew and passengers during a dispute over her refusal to wear a mask on a Hawaii-bound flight in early 2022, prompting the pilot to return to Phoenix.

New measures to protect staffers including expanding self-defense training are included in proposed FAA reauthorization legislation. Other proposals in Congress to create a new no-fly list preventing unruly passengers from flying on any carrier in U.S. skies so far haven’t gone anywhere.

Andrew Thomas, an associate professor of marketing and international business at the University of Akron, has tracked the problem of “air rage” for decades. The sharp decline in incidents since the postpandemic peak is a sign that stronger enforcement works, he said, and that many people think twice before acting out if they believe they might face steep fines or flight bans.

“You’re still gonna get the outliers—you’re gonna get the drunks, the drugs, entitled, just the mentally ill—I think you’ll still always have that, that’s just the curse of air travel,” he said.

Write to Alison Sider at alison.sider@wsj.com and Benjamin Katz at ben.katz@wsj.com