For the first time, paleontologists have discovered a fossilized tyrannosaur with its last meal preserved in its stomach—and it turns out the dinosaur was a fussy eater, consuming only the choicest parts of its prey and discarding the rest.

The discovery confirms what researchers have long suspected: Juvenile tyrannosaurs, like this one, sliced through the flesh of small prey with blade-like teeth, while adults, with chompers strong enough to crush bone, targeted giant herbivores.

Those differences mean that adults and juveniles didn’t compete for prey, allowing these predators to dominate their ecosystem throughout much of their lives, according to a study published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

The star of the new research—a 13-foot-long, 740-pound juvenile tyrannosaur known as Gorgosaurus libratus—sprinted after nimble prey through the forests of what is now Alberta, Canada, about 75 million years ago.

The meal it was afterwas a birdlike dinosaur weighing around 20 pounds. The young predator, a T. rex cousin that could run about 30 mph, overtook its quarry and with almost surgical precision severed the prey’s legs and swallowed them whole.

“I feel like this is one of those once-in-a-career fossils,” said Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary who co-led the study with François Therrien, curator of dinosaur paleoecology at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta.

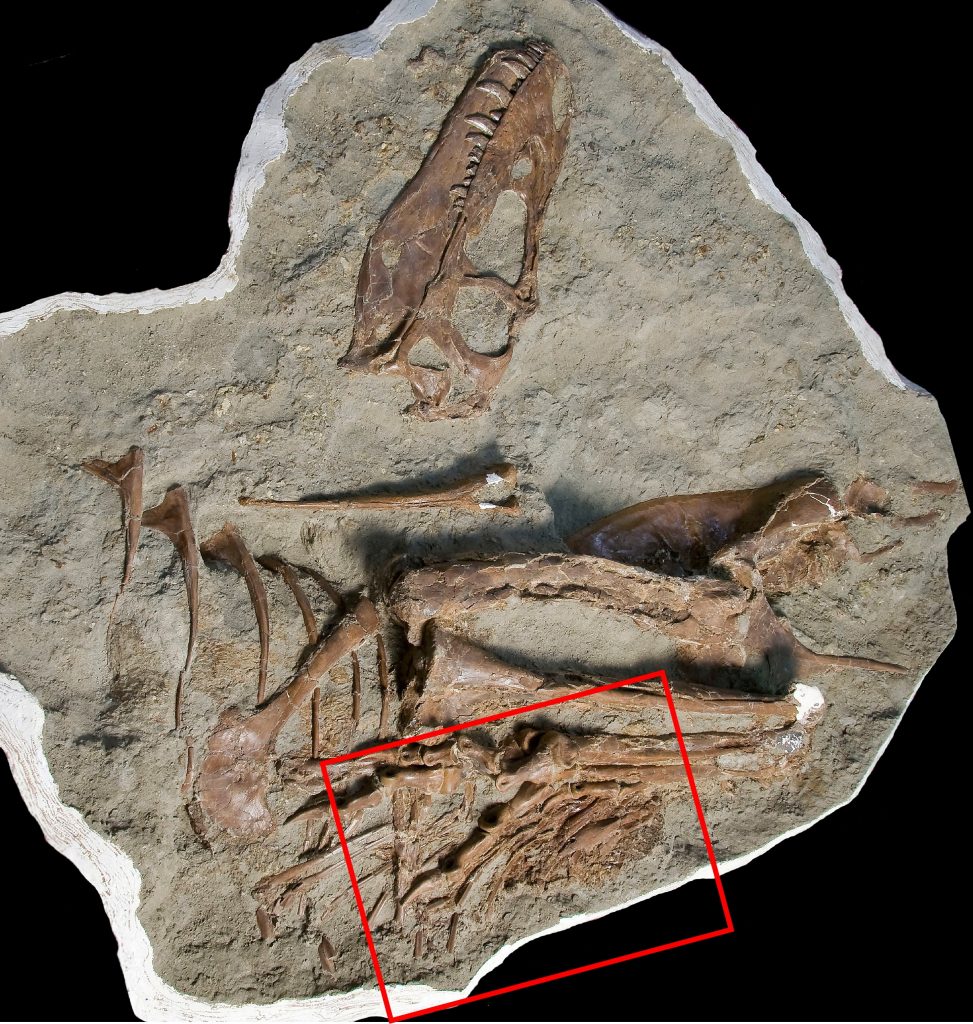

The fossilized 75 million year old skeleton of a juvenile Gorgosaurus, a meat-eating dinosaur that lived during the Cretaceous Period in what is now Canada’s Alberta province, with the left view showing the location of stomach contents?hindlimbs of a small dinosaur called Citipes, is seen in this picture obtained by Reuters on December 7, 2023. Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology/Handout via REUTERS

When the Gorgosaurus was first discovered in 2009 in Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park, the researchers didn’t realize its stomach held a surprise. Once the fossil was brought into the museum’s lab a year later, they used the skull and a femur to identify it and determine its size. A dozen or so Gorgosaurus skeletons have been discovered in the last century.

The researchers then noticed toe bones inside the dinosaur’s rib cage. Not only were those bones anatomically in the wrong spot, but they were also too small to belong to such a predator.

By comparing those bones to specimens from other dinosaurs known to have lived in this part of the world during the late Cretaceous, the scientists identified the prey as Citipes elegans—a turkey-sized dinosaur with a beak, feathers and a long neck. Further study revealed the predator’s stomach held the leg bones from two different Citipes.

The peculiarities didn’t stop there.

“We didn’t see any tooth marks, so it just seemed to have swallowed the legs whole,” Zelenitsky said. “And it was just the legs that the tyrannosaur ripped off. It didn’t eat the rest of the carcass.”

Such selective dismemberment suggests the predator was going for quality over quantity—preferring Citipes’s thick thighs to its neck and body.

“They’re smart, picky eaters,” said Thomas Carr, associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin, who wasn’t involved in the study. “It’s charming.”

The study authors eventually cut bone fragments out of both the Gorgosaurus and the two Citipes, looking for growth lines under a microscope to determine the dinosaurs’ ages at the time of death. The fragments revealed that the Gorgosaurus was between 5 and 7 years old. The Citipes were both less than a year old, and additional examination showed their bones had been soaking in stomach acids—one longer than the other, suggesting the predator hadn’t eaten them at the same time.

The prey items substantiate what a growing body of paleontological work, based on bones and soft tissue, has suggested: As the body, jaws and teeth of a tyrannosaur grew and changed throughout its life, so did its diet and hunting strategies.

juvenile Gorgosaurus, a meat-eating dinosaur that lived 75 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period in what is now Canada’s Alberta province, and a Citipes, a small feathered, birdlike dinosaur, are seen in this illustration obtained by Reuters on December 7, 2023. Julius Csotonyi and Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology/Handout via REUTERS

“Trying to close in on the behavior of ancient animals is a source of constant frustration,” according to Lindsay Zanno, head of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh. She wasn’t involved in the study.

“This fossil brings tyrannosaurs to life in full color,” she said, adding that it proves young individuals ate prey “in the most nightmarish way possible.”

Juveniles, with their narrower jaws, weaker bites and fleet-footedness, were better suited to hunt smaller, swifter prey, while slower, big-jawed adults—which could reach 30 feet in length and weigh around three tons—targeted herds of larger herbivorous duck-billed and horned dinosaurs that provided enough energy to satisfy their larger bodies.

“There just comes a point where feeding only on small prey is no longer enough to sustain you and you graduate to feeding on larger prey,” Therrien said. That transition, according to the study authors, occurs when a Gorgosaurus reaches 11 years old, or about halfway through its life expectancy, by which time the requisite changes in teeth and jaws have occurred.

Crocodiles—one of tyrannosaurs’ closest living relatives—exhibit similar shifts as they age, said Scott Williams, a paleontologist and director of exhibits at the Bozeman-based Museum of the Rockies. “It’s always kind of nice when there is something that provides direct evidence of things that we’ve been positing for a while,” said Williams, who wasn’t involved in the new work.

But ultimately, this Gorgosaurus’s death remains a mystery.

Although the fossil was found in what was once a prehistoric riverbed, that doesn’t mean the dinosaur drowned. “The animal could have died close to the river and just fallen in,” Therrien said, adding the researchers didn’t find any evidence of injuries on the predator’s skeleton.

It’s likely, though, that this juvenile predator was on its own when it died.

“By 5 to 7 years old, crocodiles are already on their own; they’re not being looked after by parents,” Therrien said, adding that tyrannosaurs of the same age would have likely been beyond the parental care phase too.

The Gorgosaurus probably wasn’t hunting in a pack either, the researchers said, given that Citipes were slim pickings.

“It’s a small animal, so once you take the meatiest part of the carcass, that wouldn’t leave much for other members of the pack,” Therrien said. “When you’re a pack hunter, you have to share the food.”

Write to Aylin Woodward at aylin.woodward@wsj.com