One of the best strategies for good health in the new year: Reduce the amount of sugar you eat.

Sugar sneaks into our diet in surprising ways, from coffee drinks you don’t realize are sugar bombs to small amounts that add up in bread or sauces. Looking more closely at nutrition labels and little tricks like putting a few cookies onto a plate rather than eating them straight from the bag can help.

It’s worth the effort, nutrition researchers say. Studies have found that diets high in added sugars are linked to a higher risk of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

U.S. guidelines recommend that Americans limit their consumption of added sugars to 10% of daily calories. The American Heart Association recommends a limit of 6% of calories. While overall sugar consumption has decreased in recent years, Americans still get an average of about 13% of their daily calories from added sugars, according to federal data.

Still, there’s an important distinction between added sugars—which are found in processed foods such as soda, cereal and yogurt, as well as honey and sugar itself—and sugar that occurs naturally in foods like fruit and dairy products. Foods that naturally contain sugar provide nutrients that people need and most Americans aren’t eating enough of them, nutrition researchers say.

“If you have an apple, yes there’s sugar in it, but it’s coming as this whole package of water and fiber and nutrients,” said Erica Kenney, assistant professor of public health nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Here are some strategies from nutrition researchers and dietitians to reduce the amount of added sugar in your diet:

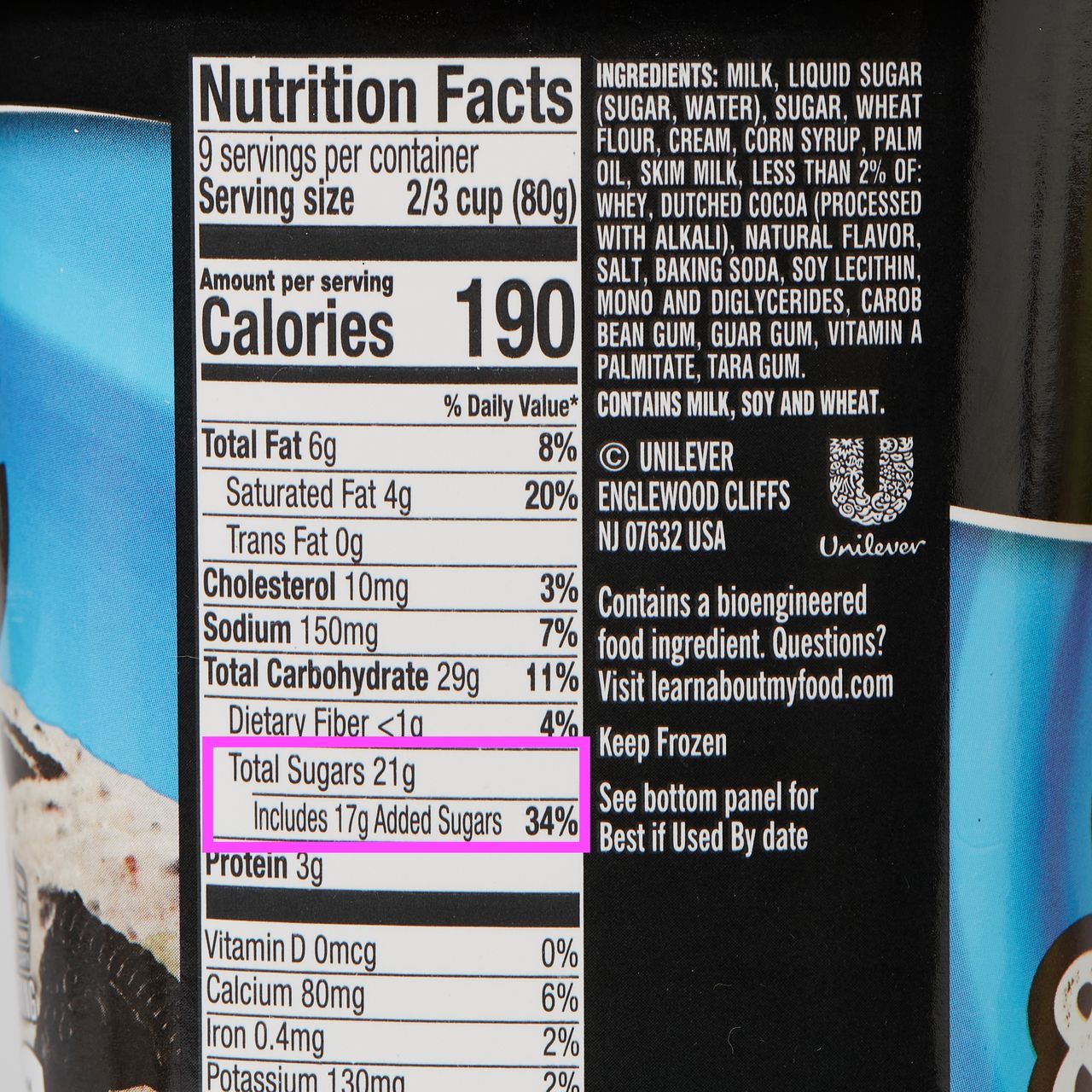

Get to know nutrition labels. The Food and Drug Administration now requires food manufacturers to list the amount of added sugar in products on a separate line on nutrition labels. The requirement is one of many governments around the world have recently instituted in an effort to get people to cut back on sugar.

Sugar comes in many forms. When you look at ingredients lists, you’ll see things like sucrose, maltose, high-fructose corn syrup and molasses. It’s all added sugar.

Non-sugar sweeteners such as aspartame, sucralose and stevia are an option, but some nutrition researchers say there isn’t enough data to know the long-term health effects of diets high in non-sugar sweeteners.

Don’t drink your sugar. Sugar-sweetened beverages are the top source of added sugars in the American diet. They make up 24% of daily added sugar intake, according to federal data.

“You just don’t need that sugar” from sweet drinks, says Kenney. “They are basically liquid candy.”

People probably know that regular soda is high in sugar, but so are many energy drinks, fruit drinks and bottled smoothies, says Alice H. Lichtenstein, director of the Cardiovascular Nutrition Team at Tufts University.

Some drinks are advertised as being fortified with vitamins to give a “health halo” around them, which may lead people to believe the products are good for them even when they’re loaded with sugar, Lichtenstein says.

Coffee and tea are the third-biggest source of added sugars, with 11% of Americans’ daily sugar intake coming from them.

Beverages, including drinks with added sugars, also don’t make you feel full quickly, which means you can easily consume large quantities of them, says Richard D. Mattes, a professor of nutrition science at Purdue University in Indiana.

Visualize teaspoons of sugar. Then make swaps. A general rule of thumb, says Harvard’s Kenney, is that 4 grams of sugar equals about a teaspoon. If a yogurt has 16 grams of added sugar, that’s 4 teaspoons. Kenney asks herself, would she add that much sugar to a breakfast she made herself?

Comparing the amounts of added sugar in different brands of similar foods can help, says Grace Derocha, a registered dietitian in Troy, Mich., and a spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. She’ll add fresh fruit, cinnamon and vanilla to plain Greek yogurt, for example, instead of buying flavored yogurt.

Pay particularly close attention to the labels of breakfast cereals and granola bars, Derocha recommends. And be wary of products that make health claims like “good source of whole grains” or “made with real fruit,” nutrition researchers advise. They may sound healthy but can be loaded with sugar.

Watch out for unexpected sources of sugar. Some foods that we don’t think of as particularly sweet can have surprising amounts of added sugars, such as bread, salad dressings, ketchup and sauces, said Lindsey Smith Taillie, associate professor in the nutrition department at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Look closely at the added-sugar line for salad dressings marketed as “low fat,” said Sue-Ellen Anderson-Haynes, a registered dietitian in the Boston area and a spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “Sometimes they add more sugar to make up for the taste,” she said. Many brands of peanut butter and almond butter can contain a lot of added sugars, too, she said.

Adjust portion sizes and frequency. Desserts and sweet snacks like cookies and doughnuts are the second-biggest source of added sugars in the American diet, making up 19% of daily calories, according to federal data.

That doesn’t mean we can never eat them, dietitians say. In general, instead of having dessert every night, make it a once-a-week treat, recommends Anderson-Haynes.

Limit portion sizes of sweets, too, says Derocha. To make ice cream less readily available—and tempting—Derocha doesn’t keep it in the freezer in her kitchen. She leaves it in the one in her garage instead.

Write to Andrea Petersen at andrea.petersen@wsj.com