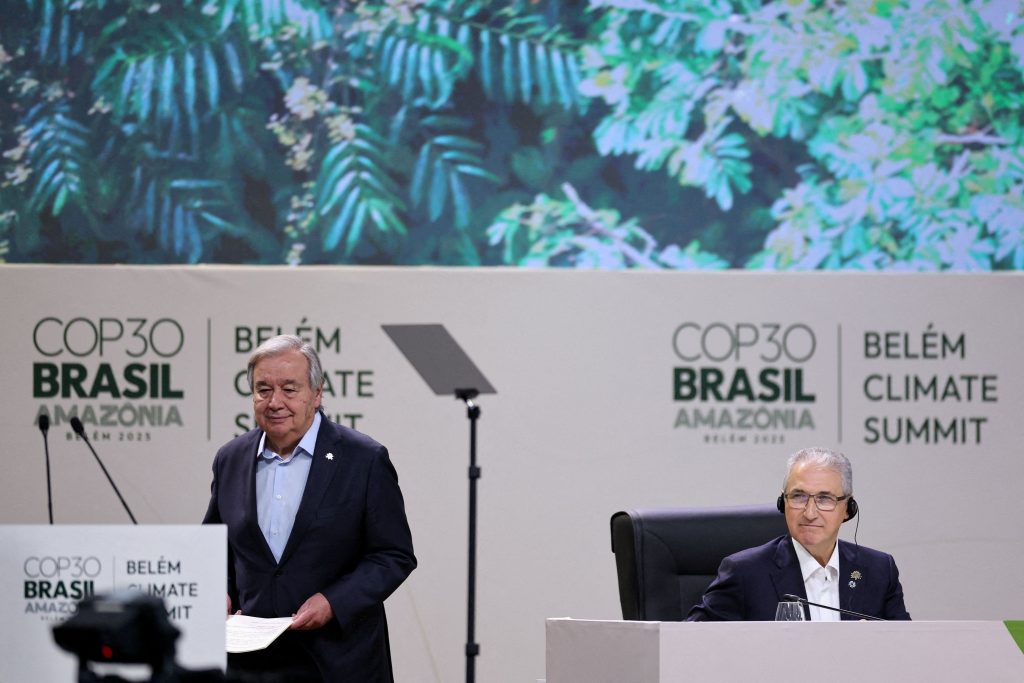

Clashes between Indigenous people and security personnel at the Climate Summit, a report from the World Meteorological Organization revealing that the past 11 years are expected to be the hottest on record, Brazil’s President Lula da Silva attacking Donald Trump for his positions and snubbing of COP30, and at the center, with a starring role, the exotic Belém—where the waters of the Amazon meet geopolitical rivalries and corporate interests. At the end of the day, however, one question remains: what have we achieved so far?

Ten years after the Paris Agreement, humanity watches yet another crucial climate summit, with the choice of Belém, according to New Yorker journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Elizabeth Kolbert, being no coincidence. “The Brazilians wanted to emphasize the importance of the Amazon for the global climate. Having something like that in the background has obvious symbolic significance. Whether it will have practical impact is hard to know.”

Kolbert, known for the book The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, which established her internationally and earned her the Pulitzer Prize, traveled from Alaska to Greenland and visited leading scientists to reach the core of the discussion on global warming. Today, she remains one of the most insightful voices in environmental journalism.

In her book, Kolbert connects scientific research with the history of human presence on Earth and, through vivid descriptions, highlights the delicate balance between progress and destruction. Having followed environmental developments and written about them for years, she can confidently say about the Paris Agreement: “The world is not on track to limit warming to 1.5°C. It wasn’t ten years ago either.”

This statement comes at a time when experts warn that without immediate and radical measures, the planet’s temperature will exceed critical limits far too soon. The second question, therefore, is how disaster can be avoided—or whether the situation can still be corrected.

Technological “correction”

In Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future (2021), which covers many of the themes from The Sixth Extinction, Kolbert examines humanity’s tendency to fix its mistakes in nature with new, often more dangerous errors. A phenomenon she observes repeating strongly. “I read about a startup that raised $60 million to develop particles to be sprayed into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight. This idea, known as solar geoengineering, is exactly the kind of ‘fix’ that could lead to even worse problems,” she emphasizes.

Humanity—or rather, the individuals directing our lives—tries to save the planet from itself using tools that could worsen the crisis. This is precisely what Kolbert focuses on in Under a White Sky: humanity’s need to control nature at any cost to prevent ecological collapse through the very intervention that caused it. From diverted rivers in the U.S. to attempts at species reintroduction via biotechnology, her book explores how the desire for solutions can lead us into an artificial world and a vicious cycle—until the cycle is finally closed. For all of us.

Kolbert also reminds that COP30 focuses on climate change and not directly on biodiversity loss, though the two issues are interconnected. “Limiting warming would obviously benefit many species,” she explains. “But climate change, unfortunately, is not the only factor in the current extinction crisis. There are many others, like habitat loss and fragmentation, and all must be addressed to make a real difference.”

A ray of hope

The location of COP30, the dance of Indigenous people outside the building where climate talks take place, the incidents, their interventions, tensions, suits, ties, hands carrying agendas—all reflect the contradictions the planet experiences. Belém is both a symbol of life and destruction. Amid everything, the only thing flourishing rapidly is denial of reality.

Most worrying, according to Kolbert, is that we live in a time when people refuse to see clearly, and this observation carries particular weight as COP30 unfolds. World leaders are called not only to negotiate targets but to demonstrate willingness to face the problem. “Climate change is, unfortunately, an issue it’s easy to look away from. It’s a crisis that moves slowly until it becomes a real crisis,” she says, citing the recent Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica as an example.

Looking to the future, the journalist and author, though cautious, sees a positive trend in the present. “If something makes me even slightly optimistic, it’s that clean-energy technologies, like photovoltaics, are becoming cheaper and cheaper. It is therefore possible that these technologies will replace fossil fuels purely for economic reasons. I honestly hope this happens.” Perhaps this economic logic—and not, unfortunately, ecological awareness—will ultimately prove to be our strongest weapon against global warming.