A decisive step toward the most extensive architectural and museological transformation in the history of Greece’s National Archaeological Museum has now been taken. The country’s two highest advisory bodies on cultural heritage—the Central Archaeological Council (KAS) and the Central Council for Modern Monuments (KSMN)—have issued a unanimous positive opinion on all preliminary studies for the project.

These include the architectural, structural, and electromechanical designs for the expansion and comprehensive upgrade of Greece’s flagship museum, which houses one of the world’s most important collections of ancient Greek art.

A project of national scale and ambition

The project αφορά the entire city block occupied by the museum complex, including the Epigraphical Museum, and aims to transform the National Archaeological Museum into a contemporary cultural institution of global standing—worthy of the treasures it holds.

The architectural design is led by the internationally acclaimed offices of David Chipperfield Architects in collaboration with Greek architect Alexandros Tombazis. Their goal is to create a unified and coherent ensemble that respects the historic character of the neoclassical monument while fully meeting the demands of a modern museum.

The studies began after the Greek Parliament ratified, in April 2024, a €40 million sponsorship agreement by Spyros and Dorothy Latsis, in memory of Ioannis and Erietta Latsis. The donation fully covers the cost of all studies required for the project.

“Greece is getting the museum it deserves”

In a statement, Culture Minister Lina Mendoni said that “Greece is getting the National Archaeological Museum it deserves,” stressing that the expansion resolves the fragmentation and inconsistencies caused by piecemeal interventions of the past and restores a unified architectural identity to the monument.

As she noted, the existing exhibition spaces—designed in the 19th century—can no longer accommodate today’s needs, following a more than doubling of visitor numbers and the evolution of modern museological standards.

The new proposal addresses long-standing structural problems such as humidity and water infiltration, strengthens seismic protection, upgrades energy efficiency, and ensures full accessibility for all visitors.

For the first time, particular emphasis is placed on guaranteeing stable and appropriate environmental conditions—humidity, lighting, and temperature—essential for the proper display and long-term preservation of antiquities, both in the historic building and in the new extension.

A new museum and a public garden for Athens

The architectural vision rests on four core objectives:

- Creating a public park as a gift to the city of Athens

- Presenting Greek cultural identity to an international audience

- Expanding the museum’s functions and exhibition areas

- Reinforcing its role as a beacon of national culture

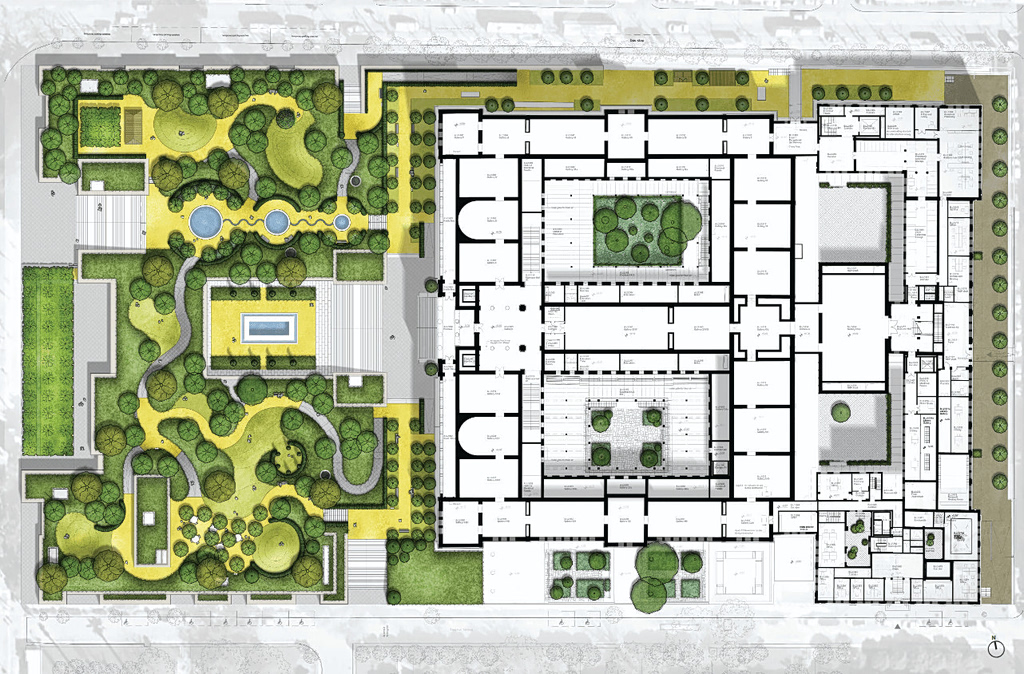

The intervention strategy includes a major underground expansion that respects the iconic neoclassical façade, a new landmark main entrance on Patission Street with a public square and foyer, and improved internal connectivity between the historic building and the extension. At street level, an open, green public park with a courtyard and bistro will provide a high-quality urban space.

The historic building itself will be enhanced through the renovation of galleries dating from the 1950s, targeted interventions along the central axis to improve orientation and circulation, and the strengthening of the museum’s research role with new laboratories and offices.

Visitor facilities will be significantly upgraded, with a central foyer, lockers, cloakrooms, restrooms, restaurant, auditorium, museum shop, and expanded areas for temporary exhibitions.

Doubling exhibition space, expanding collections

The plan foresees a major upgrade of exhibition and support spaces. Around 17,000 antiquities will be displayed across two main thematic zones, 13 sections, dozens of subsections, and focused narrative units.

The galleries of the three Prehistoric Collections—Neolithic, Cycladic, and Mycenaean—will more than double, expanding from 1,100 to 2,500 square meters. Temporary exhibition space will also more than double, from 429 to approximately 1,033 square meters, with dedicated storage and logistics areas.

Educational spaces will increase from just 50 to 178 square meters, while storage areas for antiquities and general use will expand from 3,367 to 4,296 square meters. Conservation laboratories will grow from 856 to 1,707 square meters, the library from 201 to 289 square meters, and the historic photographic archive from 39 to 91 square meters, with new dedicated storage areas. Interior courtyards will also be activated, creating a modern, functional, and educationally rich environment.

A new cultural axis for the city

The preliminary architectural study envisions not only a new museum but also the broader regeneration of the Exarchia, Patission, and Metaxourgeio areas. The project aims to create a new cultural axis linking the museum with the National Technical University of Athens, the Acropolis, and the Pedion tou Areos park.

The ambition is to establish the museum as a landmark of the city, a major research center for the study of antiquity, and an open, universally accessible public garden functioning as a hub of culture and leisure.

A coherent visitor journey through Greek civilization

The approved museological concept offers a complete visitor route tracing the evolution of Greek civilization from the Neolithic period to Late Antiquity. The full exhibition unfolds across four levels—two in the new extension and two in the historic building—organized around a central axis that ensures clear orientation and narrative continuity.

In the extension, exhibition spaces alternate between large, free-flowing galleries with diagonal views and access to natural light, and more intimate “cabinet” rooms designed for focused, contemplative encounters with objects. A central water element in the underground level provides both orientation and a sense of natural illumination.

In the historic building, the sequence of galleries along the central axis presents the development of Greek sculpture from the Archaic to the Classical period, enhanced by varied scales and lighting conditions.

Educational spaces—four flexible classrooms that can be combined or separated as needed—are deliberately placed at the heart of the complex, underscoring the museum’s educational mission. Direct access to the café courtyard enables outdoor learning activities.

A green threshold on Patission Street

At the museum’s Patission Street entrance, a grove of plane trees will create a shaded threshold space that preserves clear views of the building while reducing dust, heat, and direct solar radiation. The park will function as a welcoming antechamber to the museum, remaining pleasant even during Athens’ hottest summer days.

The park will be fully accessible via stairs, ramps, and elevators, with main paths 2.5 meters wide and level changes bridged by ramps built from reused marble blocks. The park will close after midnight, secured by discreet fencing integrated into the vegetation.

Infrastructure built for the future

The electromechanical design fully aligns with the architectural, structural, and museological studies, as well as with planting and lighting plans. Systems have been selected to protect exhibits, ensure optimal environmental conditions, reduce energy consumption, and allow for easy maintenance and future expansion.

These include modern plumbing, active fire protection, specialized gas installations for laboratories, HVAC systems, electrical networks, and new elevators.

Structurally, the existing building—comprising two parts with fundamentally different load-bearing systems—has been thoroughly assessed. Based on this analysis, and in coordination with architectural and mechanical requirements, targeted structural interventions have been optimized to meet seismic safety and functional needs.

A monument shaped by history

The National Archaeological Museum opened at its current location in 1889. Designed initially in 1865 by Ludwig Lange and later modified by Panagis Kalkos, Armodios Vlachos, and Ernst Ziller, it evolved through multiple construction phases—from the late 19th century neoclassical wings to modernist interventions by Patroklos Karantinos after World War II, and seismic upgrades following the 1999 earthquake.