The region has a long history of hiding its rivers and streams – the very streams and rivers that were regarded as sacred in antiquity. Eridanos, a tributary of Ilissos river, which today flows under the feet of modern Athenians and visitors of the city’s historical center, was hidden from public view during the Greek and Roman periods. Interventions in Eridanos started in the 4th century B.C. and culverting was completed in 117-138 A.D.

The decision to culvert Eridanos was taken with public hygiene in mind. Due to the ephemeral nature of the river, there were frequent overflows mixed with sewage that created a nuisance and brought with them the risk of diseases. At the same time the abundance of soil-covered permeable surfaces, allowed for adequate infiltration of runoff and did not raise flooding concerns.

Ilissos – originally a tributary of the larger Kifissos River that was later rechanneled to drain into the Saronic Bay — suffered the same fate almost 2,000 years later. The culverting of Ilissos officially started in 1939 (Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas proudly proclaimed that, “Today we are burying the River”) and was completed in the 1950s. Although beloved by Athenians, Ilissos was characterized as nuisance and, at the same time, used as a source of inert materials for use in the city’s booming construction industry. Its culverting provided additional space for new roads, while the many benefits of the river, such as flood protection, were ignored.

More recently, Kifissos itself has become semi-enclosed with concrete structures, prioritizing the creation of a motorway over the natural flow of the river, while downstream it currently forms part of the city’s sewage system.

These radical alterations of the Athens basin’s natural aquatic environment have raised serious concerns related to the basin’s defense against flooding and of course to the degradation of its natural environment.

Is it possible to reverse the mistakes of the past and revive the lost waterways of Attica? Many modern cities have gone for such ‘daylighting’ projects aiming for sustainable water management and urban landscaping. Daylighting projects involve revealing the ‘hidden’ rivers and streams partially or in their full length; enabling supporting works on river banks, upstream and downstream; re-introducing native vegetation; increasing green areas and permeable surfaces in cities; supporting the catchment with new water features and with nature-based solutions for rainwater management.

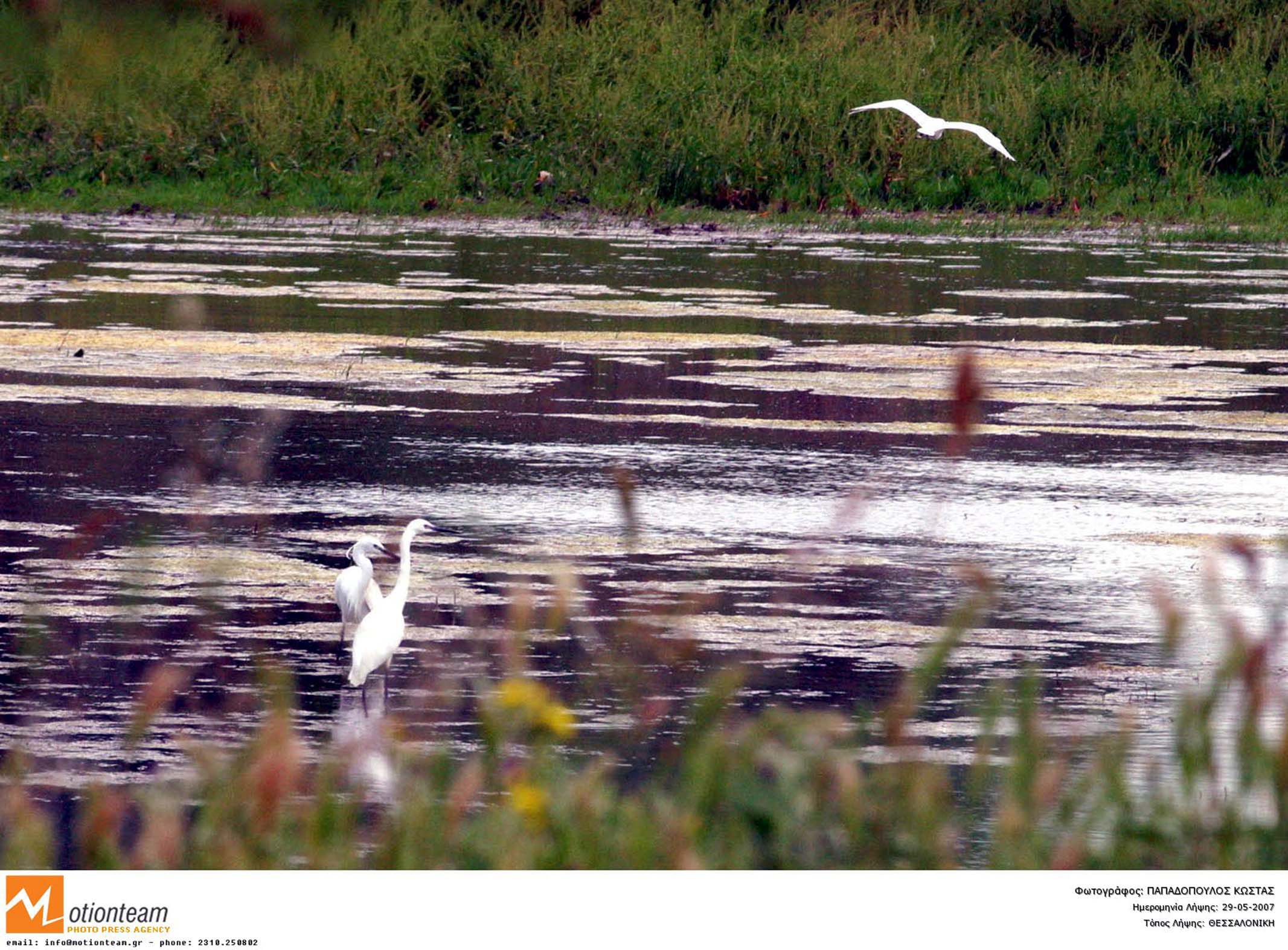

The solutions mimic natural processes, both in function and appearance. They enable high levels of rainwater infiltration through gravel of different sizes and soil into either the drainage network or a groundwater aquifer or even in storage facilities for reuse. The systems can be placed below or above ground. Examples include vegetated infiltration beds; infiltration trenches; rain gardens; swales; permeable pavements; detention basins; retention ponds and constructed wetlands.

Nature-based solutions have been prioritized in E.U. research and innovation policies and funding schemes (E.U. Green Deal; E.U. Horizon Calls).

Their benefits are indeed multiple, starting from being identified as adaptation and resilience measures for climate change. They have the ability to capture carbon and act as carbon sinks. In addition, they ameliorate some of the impact of climate change, such as flash flooding, landslides and erosion, they regulate temperatures, heatwaves, and droughts, improve water flow and the soil’s water-holding capacity. Nature-based solutions also provide natural cooling effects contributing to the reduction of the urban heat island effect, thus creating more livable and sustainable cities. The pollutant-removal effect is achieved via infiltration through inert materials and the reduction of biodegradable materials in the open water bodies. Thus, such systems improve the ecological status of watercourses, a basic requirement of the E.U. Water Framework Directive. Last but not least, we should not ignore the water reuse potential, particularly important for regions of increased water stress; the obvious biodiversity and ecosystem benefits; the related economic benefits; and the undeniable added aesthetic value in a city where water features are visible.

How feasible are those interventions? Is it possible to reveal Athenian rivers? Yes, albeit not to their full length and potential. However, scientific knowledge and good daylighting examples from other big cities, indicate that sustainable change is possible and desirable.

A notable example is the Cheonggeyecheon stream in Seoul, an 11 km-long restored stream that runs through a densely built area of the Korean capital. The natural stream was part of Seoul’s early sewerage system until the mid-20th century. It was culverted in the post-Korean War era to construct an elevated freeway. Today, after regaining its natural form, it provides significant flood protection for up to a 200-year flood event, it reduces the urban heat island effect with a temperature decrease ranging from 3.3-5.9°C and has become a landmark of the city. The economic gain is also high and is derived from reduced flooding, a rise in land and property values, and growth for businesses and tourism.

The Dunfermline Eastern Expansion in Scotland is the largest site in the U.K., where nature-based solutions formed a planning condition instead of conventional drainage systems, affecting an area of 5.5 square kilometers.

The reduced risk of flooding in the lower part of the Kifissos River as well as climate adaptation and resilience building, sustainable cooling of the city and protection of human health and wellbeing –all priorities in the recently concluded COP28 — could be achieved through similar interventions in Attica.

* Dr. Apostolaki, is Executive Director of the Centre of Excellence in Sustainability at the American College of Greece (ACG). She is Assistant Professor in the Program of Environmental Studies, Department of Science and Mathematics of Deree – The American College of Greece.