Modern governance increasingly confronts a paradox. States are expected to solve problems—technological disruption, climate risk, infrastructure decay, social fragmentation—that resemble the coordination challenges of large organizations. Yet political institutions were not designed as firms. As Plato observed in the Republic, the organization of the polis must balance knowledge, moral purpose, and capacity; exposing society to unmoderated power or knowledge risks instability. The question is not whether governance should imitate business logic, but under what conditions certain organizational principles travel—and where they break down.

This tension is visible early in the contemporary landscape. Investment in research, infrastructure, and industrial capability now requires long time horizons, feedback mechanisms, and system-level coordination. Dan Wang’s recent book Breakneck captures this reality vividly. China, Wang argues, operates as an engineering state: a system that plans, tests, measures, and recalibrates continuously. It is not governed primarily by ideology, nor by spontaneous markets, but by iterative learning at scale, turning the country into a civilizational laboratory where policy is treated as an engineering problem rather than a purely political one. Against this backdrop, earlier experiments in business-like governance appear less anomalous—and more conditional.

Corporate Logic and the State: A Limited Translation

The idea that states might borrow from corporate governance has long circulated among economists. Renowned Greek economist George Bitros articulated this cautiously, arguing that political systems could, in principle, adopt characteristics of well-run firms: clearly defined objectives, aligned incentives, performance monitoring, and institutional accountability. Citizens, in this framing, resemble stakeholders; legitimacy flows not only from procedure, but from sustained performance.

Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew remains the clearest real-world approximation of this logic. From independence, the city-state rejected ideological pluralism as its organizing principle, emphasizing administrative competence, meritocratic recruitment, and long-term strategic planning. Government ministries were expected to behave like integrated units within a single organization: objectives were explicit, authority centralized, and execution disciplined. Political remuneration also reflected this ethos: senior ministers and officials were paid at levels explicitly benchmarked to top private-sector salaries, underlining the idea that public leadership should compete with corporate management for talent and integrity. From a Platonic perspective, such remuneration is defensible only if it insulates governance from corruption rather than serving as a reward for power itself—acceptable as an instrument, but suspect if it displaces civic virtue as the organizing principle of rule.

A crucial figure in Singapore’s early development was Dutch economist Albert Winsemius, formerly associated with post-war reconstruction planning in the Netherlands. Invited by Lee in the early 1960s, Winsemius advised over two decades, focusing on methods: benchmarking international best practice, identifying comparative advantage, sequencing reforms, and insisting on administrative realism. Lee summarized the ethos bluntly:

“We learned on the job and learned quickly. If it did not work, we did not waste time. I made it a practice to find out who else had met the problem we faced, how they had tackled it, and how successful they had been.”

Singapore learned by benchmarking peers—sending officials abroad to study ports, airports, housing systems, and education models, then adapting what worked. Under these conditions—small scale, social cohesion, centralized authority—Bitros’ corporate-governance logic could function without hollowing out political legitimacy. The state did not merely govern like a firm; it was small and cohesive enough to behave like one.

When Scale Changes Everything

China exposes the limits of translating firm-like governance to civilizational scale. A polity of continental size cannot be run as a unitary enterprise: social diversity, regional disparity, and historical depth make centralized optimization both risky and brittle. Governance therefore evolved along a different axis—ecosystem management rather than firm control.

This logic crystallized during the reform era under Deng Xiaoping, who observed Singapore firsthand, visiting the city-state and meeting Lee Kuan Yew to study its administrative discipline. China absorbed not a blueprint, but a method: learning by observation and adaptation. While Singapore’s high-pay approach attracted elite talent through market-like incentives, China deliberately kept senior officials on modest, standardized salaries, relying on status, authority, and long-term political security to motivate cadres.

Reforms were tested locally—most famously in Special Economic Zones—before being scaled. Knowledge was absorbed incrementally; failure was contained; success replicated selectively. The guiding principle echoed an ancient injunction: Παν μέτρον άριστον—nothing in excess. Reform was not rejected, but paced.

At this scale, the corporate analogy dissolves—but the learning logic survives. Feedback, experimentation, and outcome sensitivity remained central, yet were embedded in a system designed to manage heterogeneity rather than eliminate it. China learned not by copying peers wholesale, but by studying systems—industrial ecosystems, logistics networks, research infrastructures—and reconstructing them at civilizational scale. Dan Wang’s Breakneck provides a contemporary lens: China today is not merely executing policy; it is engineering capacity. Universities, research institutes, infrastructure platforms, and industrial supply chains are coordinated to absorb knowledge rapidly while preserving social intelligibility. Learning is institutionalized; adjustment is continuous.

Plato’s Kallipolis and the Governance of Knowledge

Plato’s Republic offers an unexpectedly modern frame. In the kallipolis, economic activity exists but is subordinated to moral purpose. Knowledge is disclosed according to civic capacity; illumination is paced. Plato’s warning is not against knowledge itself, but against unregulated exposure—a theme crystallized in the allegory of the cave.

This logic reappears in modern form through green trade finance. Rather than treating trade and capital as value-neutral, green trade finance embeds normative constraints into financial architecture. Access to credit, guarantees, and trade facilitation is conditioned on environmental performance and long-term risk. As Sun Jin et al have argued, sustainability becomes an epistemic filter within the trade system itself. Green trade finance translates complex environmental data into actionable financial signals without overwhelming institutional capacity. Markets are governed, not sovereign.

Figure 1 and the Architecture of Learning

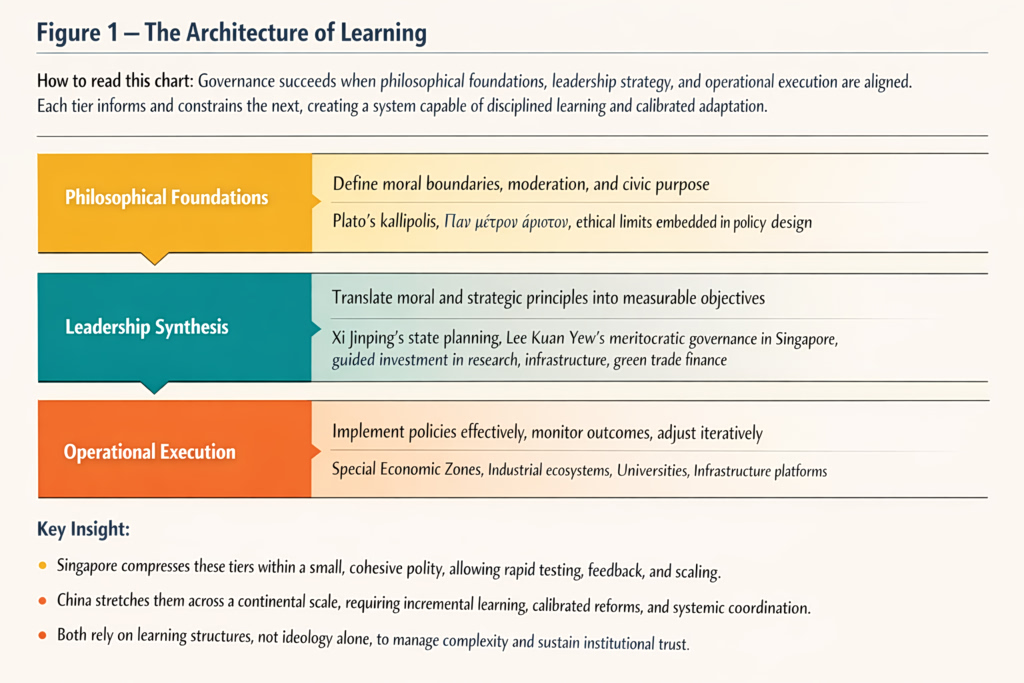

As illustrated in Figure 1, governance succeeds when philosophical foundations—Plato’s moderation and moral restraint—inform leadership synthesis, which in turn shapes operational instruments such as planning systems, research investment, and green finance. Singapore’s model fits this architecture because its tiers compress easily. China stretches them across scale, requiring mediation, pacing, and redundancy. Both rely on learning structures rather than ideological rigidity.

Democratic Fatigue and Institutional Trust

This comparative lens helps explain contemporary democratic fatigue. Public distrust often reflects not hostility to democracy itself, but frustration with institutions that no longer learn visibly or coherently. When policies cycle without correction, complexity overwhelms comprehension, and accountability dissolves into spectacle, legitimacy erodes.

Engineering-state systems illuminate both the strengths of disciplined learning and the costs at which it is secured. Democracies cannot—and should not—transform themselves into engineering states. What they can do is relearn how to reform cautiously, absorb evidence, and exercise moral restraint without surrendering openness. Trust is rebuilt when institutions demonstrate that they can observe reality honestly, adjust without panic, and govern complexity without excess. That thread runs from Plato’s kallipolis, to Winsemius’ pragmatism, to Bitros’ corporate analogies, and to the engineering states of the present.