You may not have been “ready for a long time” in the literal sense. But you did prepare methodically for your own “from the depths” confession. You worked hard to present “your truth.” Yet the first to express distrust—before your memoirs even reach bookstore displays—are the people who were once closest to you. They are neither convinced by your ghostwriter’s intentions nor willing to credit you for the excellent marketing. In the end, they will even fault you for the lyrical brushstrokes you used to dress your narrative. They will say your truth “is a fairy tale.” Why? Others have written their memoirs without kicking up so much dust. Neither François Hollande with Lessons in Power nor Tony Blair with his Journey nor Angela Merkel with her Freedom. Why such a storm over Alexis Tsipras’s Ithaca?

One explanation is that our Balkan temperament does not tolerate this type of refined memoir. Blair wrote with the requisite tenderness about his mornings in the kitchen of 10 Downing Street with Cherie. Fine. He expressed syrupy gratitude toward the Cabinet Secretary he inherited from Major’s Tories while admitting his own inexperience in governing. Fine. He confessed that he ate bananas to overcome his anxiety during his heated exchanges with his opponent in the raucous House of Commons. Again, fine. But here, in this corner of the Balkans, how can you say you became certain you were doing the right thing because you “released a trapped dove” without provoking the strongest bursts of mockery and irony? Quite simply, you cannot.

But there is another explanation as well. It suggests that none of Tsipras’s autobiographical counterparts linked their narrative to a political comeback. The others presented their recollections as veterans of power. Tsipras presents his as someone who, in his own words, “is not retired.” Thus the autobiography becomes part of a political plan. And the path of return becomes all the more difficult.

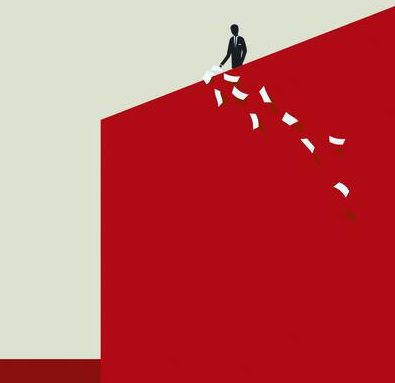

More epicly, the road to Ithaca will have its Cyclopes and its Laestrygonians. More realistically, the problem was posed within Tsipras’s circle as a question from a pragmatist: “Are we ready for the beating we’re going to take?” That remains to be seen. In any case, the question is not only about the endurance of his comrades. It relates mainly to the likelihood that the balance between praise and negative publicity—in TV studios, in traditional media, and on social media—will probably tilt toward the latter. Something that matters less for the publishing venture than for the politics.

With Ithaca, Alexis Tsipras is attempting not only to return to politics but also to create a heavyweight opposition pole. But what opposition has ever found its luck in an environment of “shock and awe,” where, beyond the classic rivals, former comrades fire indiscriminately with their familiar spite, and Internet trolls hide behind anonymity?

The danger is not the “beating that will fall.” It is that the publishing event degenerates into a political brawl of the sort in which the Left eagerly engages, splintering even into its most minor factions. A danger for whom? For the “comrades,” of course. But above all, for a political system in which one pole deteriorates day by day and the other is still struggling to construct an “alternative proposal for governance.” Now that is shock and awe.