The far right is on the rise. Geert Wilders, who’s anti-Muslim far right Party for Freedom (PVV) recently won the Dutch parliamentary election with 37 seats, is but one example. Elsewhere in Europe, many far right parties have improved their electoral performance over time. The list is long: Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN), The Sweden Democrats (SD), the Danish People’s Party (DF), the Alternative for Germany (AfD). Others have held- or continue to hold- government positions: the Lega (Italy) and the Brothers of Italy (FdI), the Austrian Austrian Party for Freedom (FPÖ), Orban’s Fidesz, the Finns Party (PS) and the Polish Law and Justice (PiS). Looking at a map of Europe, one struggles to find a country with no far right: even in formerly negative cases such as Spain and Portugal, Vox and Chega are now making the headlines. The phenomenon extends beyond Europe: a few weeks ago, Argentina’s Javier Milei won the Presidency, mobilising young voters’ discontent with the country’s poor economic performance and increasing inequality.

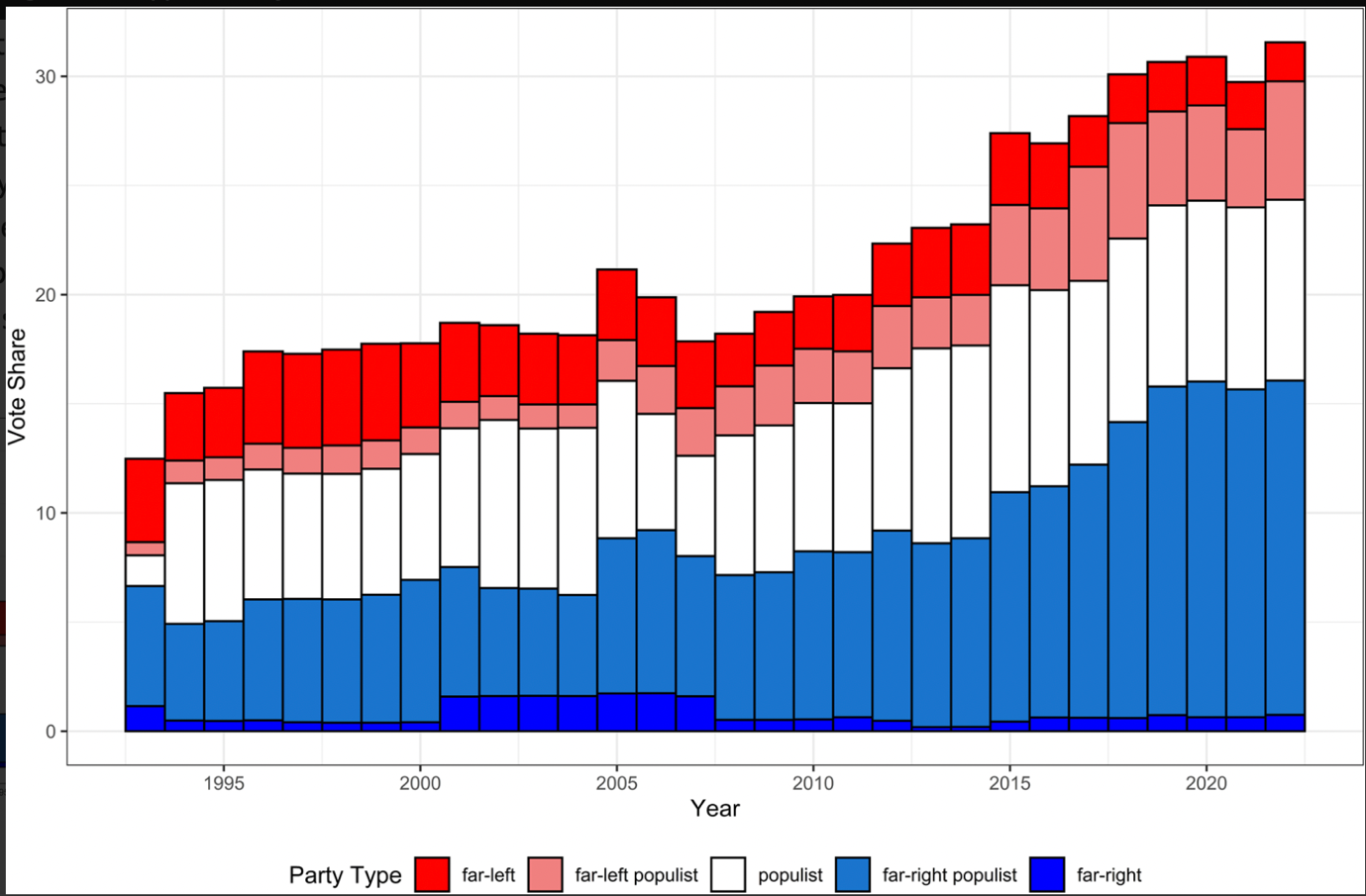

The bigger problem is not just the vote share but also the entrenchment of the far-right parties in the system. Should we be surprised? Not necessarily. This phenomenon has been brewing for decades. A look at the longer term, at least in Europe, reveals a stark picture: in national elections last year 32% of European voters opted for an anti-establishment party compared with 20% in the early 2000s and 12% in the early 1990s. About half of anti-establishment voters support far-right parties – and this is the vote share that is increasing most rapidly.

This is largely the result of far right normalization: a rhetorical streamlining and a conscious and strategic distancing from fascism and extremism. Most successful European far right parties frame their exclusion not along ethnic, but along civic nationalist lines. While at their core is a purported distinction between in-group and out-group (natives versus immigrants), they justify this distinction on ideological rather than biological criteria of national belonging. Geert Wilders’ PVV, builds its exclusionary Islamophic agenda using a purportedly inclusive narrative that centres on democratic values along the lines of ‘we must not tolerate those who are intolerant of us’. This narrative is much more difficult to counter than traditional racism. Other parties in the system contribute to this far right normalisation. Competing on far right issues legitimises and emboldens the far right, but does not win the mainstream any votes.

Normalisation makes these parties more broadly appealing to voters. Indeed, the far right voter base is much more diverse than we might initially assume. Immigration is one factor driving voters to support the far right, but it is not the only factor. In addition, immigration itself is a muti-faceted concept: whilst some voters may oppose immigration for cultural reasons, others are driven by economic concerns, fearing immigrants as competitors in the labour market. Far right parties link immigration to a broad range of societal problems. Those voters with strong cultural concerns- the far right’s core ideological voters- are a relatively small group numerically. The largest group of far right voters are protesters- peripheral voters driven by discontent. Their concerns range from material insecurity, lack of access to welfare, declining social status and a distrust in institutions.

Should we be worried? Yes. Although some of these developments have been stalled or overturned- e.g. Trump and Bolsonaro have lost power (for now), and PiS was recently outvoted in Poland- the far right remains powerful and entrenched in many countries across the globe.

The far right is no democratic corrective. Once in power, far right parties subvert democratic norms, erode liberal democratic institutions and introduce constitutional changes, undermining the judiciary and media, designed to outlast them. Their systemic entrenchment leads to the normalisation of extreme ideas and feeds the divisive dynamics of political polarisation. They are also bad for the economy. This is worrying for the future and prosperity of our democracies. Mainstream parties need to stop playing copycat, and instead develop viable alternative strategies that foster consensus and societal stability and address the many real problems that voters face.

*Professor Daphne Halikiopoulou is Chair in Comparative Politics, University of York