Sparked by the Syrian refugee crisis of 2015, which saw one million refugees and migrants pour into the EU, the recently passed EU Pact on Migration and Asylum is the result of nine years of negotiations.

“The Pact”, as it has quickly come to be known by policymakers, was passed by the European Parliament in mid-April and adopted by the Council of the EU this week. But the one thing everyone seems to agree on is that no one is happy with it.

Introducing five new regulations to manage migration and create a common EU asylum system, the Pact focuses on securing external borders, ensuring fast and efficient procedures, creating a system of solidarity and shared responsibility for migrants amongst EU member states, and embedding migration in international partnerships.

The Pact only needed a qualified majority to pass through the Council, so it could still be ratified this past Tuesday despite Poland and Hungary voting against it, the Czech Republic and Slovakia abstaining from most of its elements, and Austria voting against the Crisis regulation.

Next, the European Commission needs to present an implementation plan in June, with member states required to submit their own plans by January 2025 and to be ready to implement the Pact in about two years’ time.

The Context

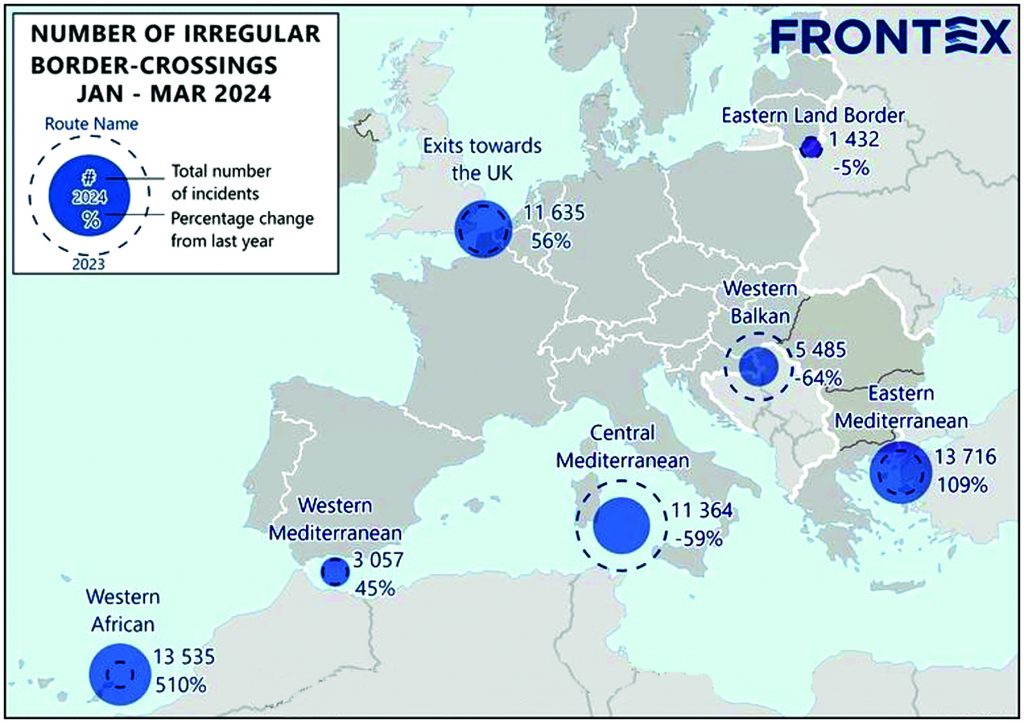

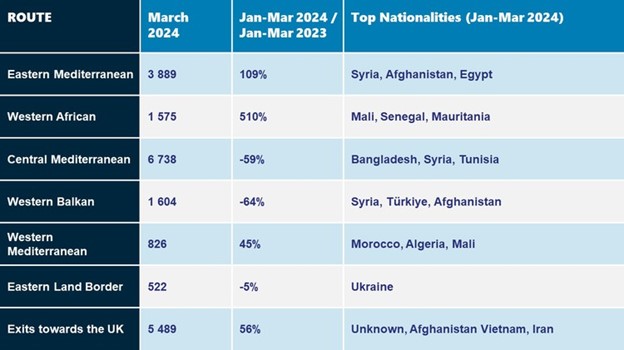

The agreement comes on the heels of 2023, and the highest levels of irregular migration flows to the EU since 2016, and of a 109% increase in irregular crossings in the Eastern Mediterranean in the first quarter of 2024, as reported by the EU’s Border and Coast Guard Agency FRONTEX.

For Greece, the more than doubling of irregular crossings in the Eastern Mediterranean route, which often goes through Greece, is of particular concern.

In addition, FRONTEX’s reports that the nationalities making the journey to Europe are predominantly from Syria, Afghanistan and Egypt make the recent partnership between Greece and Egypt, along with renewed efforts between Turkey and Greece to collaborate on migration, even more important.

However, given current migratory trends, the potential for additional pressures from geopolitical instability in the Eastern Mediterranean and climate change, and the historically problematic collaboration between Greece and Turkey on migration, one might be forgiven for wondering if the Pact will prove to be ‘too little, too late’.

Source: Frontex

The Pros of the Pact

Τaking a look at the more positive elements of the agreement, Head of Migration at ELIAMEP Dr. Angeliki Dimitriadi says that the Pact’s provisions on “mandatory solidarity”, reception standards and resettlement are steps in the right direction.

Mandatory solidarity requires governments to support the management of migrants and gives EU countries a choice: they can relocate a certain number of them, finance operational support for their management in other countries, or pay 20,000 euros for each one they reject.

How “solidarity” will actually play out remains to be seen, explains Dimitriadi, as countries like Greece will likely prefer to relocate migrants over other forms of solidarity, while other EU countries have already declared that they will not take in any migrants through relocation.

Also, deportation doesn’t work, as seen during 2003, when only 28,900 of 105,000 irregular migrants with a deportation order were actually returned, explained Dimitriadi.

“The second ‘positive’ is that member states should ensure a certain level of reception standards for asylum applicants in terms of housing, education and health. And asylum seekers will be able to access work no later than six months after submitting application for asylum.”

Pope Francis visits the Refugee Camp of Kara Tepe in Mytilene, Lesbos, during his three days visit in Greece on Dec. 5, 2021 / Επίσκεψη του Πάπα Φραγκίσκου στο Κέντρο Υποδοχής Προσφύγων του Καρά Τεπέ, Μυτιλήνη, Λέσβος, κατά την τριήμερη επίσκεψη του στην Ελλάδα. 5 Δεκεμβρίου, 2021

On the expediting of asylum-seekers’ access to the labor market, UNHCR Representative in Greece Maria Clara Martin has previously stated to media that, “These measures […] respond in a pragmatic manner to workforce needs in Greece’s productive sectors that remain unfulfilled, and promptly puts asylum-seekers on the path to self-reliance and inclusion, which in the end will yield significant socio-economic returns for all.”

Finally, Dimitriadi said, “The new voluntary framework around resettlement may help create safer pathways to the EU for refugees that need protection, as it allows member states to host them, yet the operability of this is yet to be seen.”

And the Cons

At the end of 2023, a group of fifty human rights organization across Europe penned a letter to Commission negotiators, the Spanish Presidency and the European Parliament warning that “there is currently a major risk that the Pact results in an ill-functioning, costly, and cruel system that falls apart on implementation and leave critical issues unaddressed.”

Dimitriadi also notes the shortcomings of the Pact and says that there are positive elements, but overall, it “does not provide a solid balance between solidarity and responsibility and it is still too oriented towards deterrence.”

Researchers and policy analysts are also concerned about the operability of the provisions of the Pact, its capacity to withstand future migration crises, and the level of protection that may be offered to migrants.

Called “the Crisis regulation”, a provision contained in the Pact is intended to provide quick protocols with operational support and funding in emergency situations, while also protecting EU Member States and migrants themselves from being used as political bargaining chips, according to EU statements.

FILE PHOTO: Children raise their hands in front of a column of the Erechtheion temple at the Acropolis hill during a symbolic protest against racism in Athens March 21, 2014. REUTERS/Alkis Konstantinidis/File Photo

But human rights organizations would have preferred a further buttressing of the Temporary Protection Directive, which has proved successful in supporting Ukrainian refugees after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and been applauded for its “human” approach.

However, one element that is glaringly absent from the Pact relates to the integration of third-country nationals in the EU.

Integration policies—on, for instance, integration into the labor market, discrimination or vulnerability—interact with and shape socio-economic issues in complex ways.

And integration policies and procedures can be a driver for intra-EU migration, particularly as EU countries battle demographic issues and vie for skilled and unskilled laborers from within and outside of the bloc.

Yet it appears that what happens to migrants after they receive the paperwork they need to stay in the EU remains largely at the discretion of individual EU member states, at least for now.